Beauty Banks: The Dos and Don’ts of donating

View this post on InstagramLoads of amazing donations! Thanks so much. ❤️❤️❤️ #beautybanks

A post shared by Beauty Banks (@thebeautybanks) on

The Dos

Sanitary products

Big brand supermarkets often sell these on offer, keep one packet for you, donate the other

photo credit @always_uk_ireland

Savlon / Germolene

This antiseptic essential is less than £2.00 in Superdrug

Lipsticks

Lipsticks can act as a pick me up, and can be found for under £5 in supermarkets like Morrisons

Hotel Minis

Travel size shower gels, shampoos, conditioners and body lotions are useful, and don’t have to be from a hotel- Sainsbury’s sell packs of Nivea travel essentials which include body wash and makeup wipes

Deodorants

These can be purchased for a pound or less in shops like Savers

deodorant and lipstick – two of the products that can easily be donated, photo credit @niveauk

The don’ts

While Beauty Banks are always grateful for donations, there are certain products they are not able to receive

Hairdye

FakeTan

Medicines

Anti-Ageing products

Perfume

Nail Polish

When you have gathered together your donations, you can visit Drop Point to find the nearest place to leave your donations, or find out how to post them

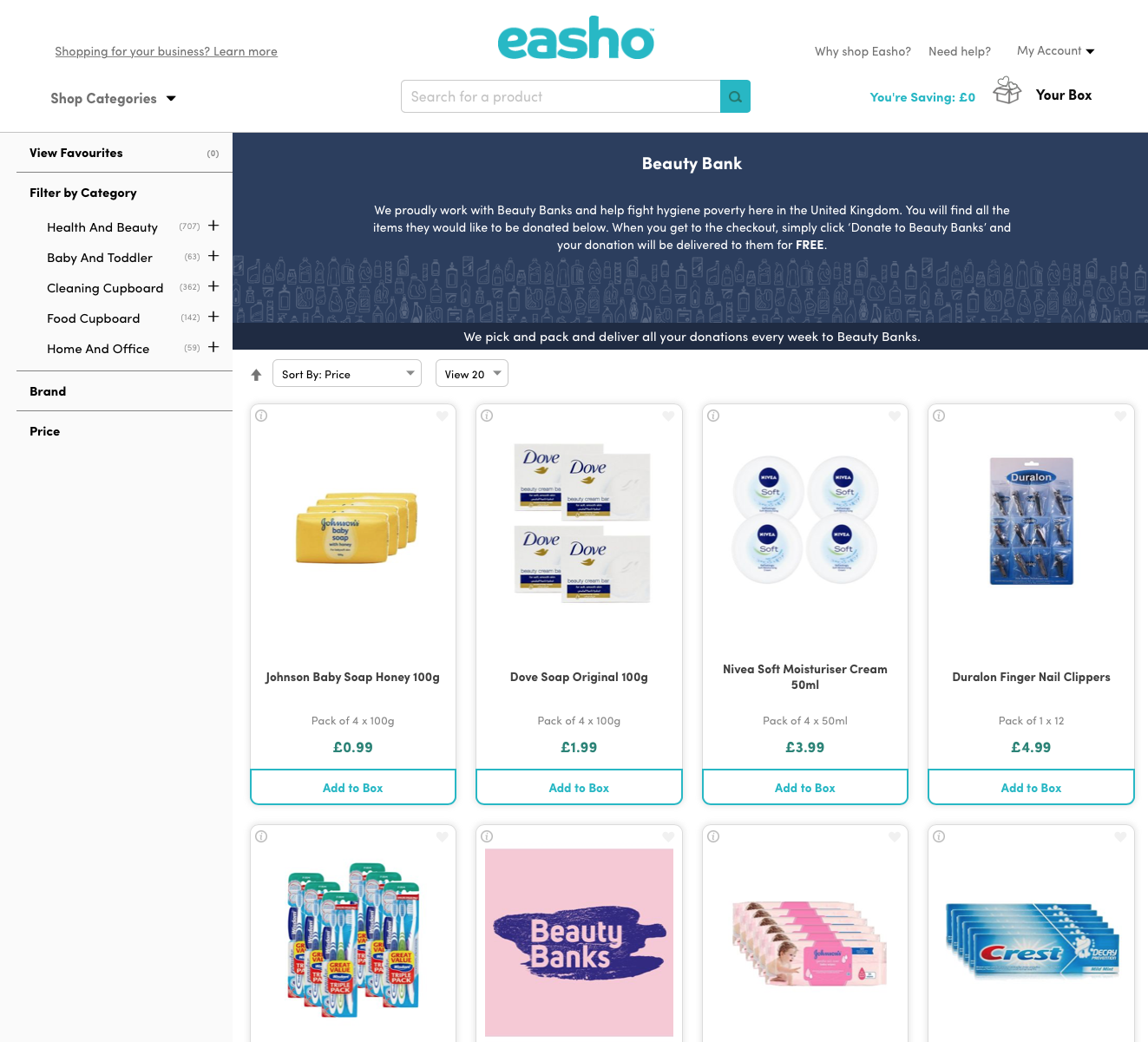

To cut out the middle man, sites like Easho pick, pack and deliver your donations direct to your chosen charity

When millions in the UK are living below the breadline, what value can a beauty product hold?

Sali Hughes, The Co-Founder of Beauty Banks, sorting donations to be sent to shelters, schools and charities across the UK, photo credit @thebeautybanks

At this time of year, as the weather becomes colder and the needs of those in poverty become more severe, it only takes a trip to your nearest supermarket to stumble across collections for your local foodbank. At the front of many big-name stores across Wales and the rest of the UK, masses of canned goods are collected and distributed across the country to feed those who cannot afford to eat during the winter months- a time when a hot meal becomes all the more crucial.

It may seem surprising, therefore, to find that in many locally run collections this year, the usual tinned goods and other long-life foodstuffs are not at the top of the list of desired donations. Instead, many churches and other charitable organisations across Wales are now asking people to count up and contribute their unopened toiletries; calling for razors, shampoo and shower gels, rather than baked beans or dried pasta.

These types of collections are operating on a larger scale too. In Kind Direct, for example, is a charity who has been operating since 1997, and over the past two decades has donated what they refer to as ‘consumer goods’ to those in need, ensuring that no usable product is wasted.

Similarly, at just the beginning of this year, Sali Hughes – who is the resident beauty columnist for The Guardian – and her colleague Jo Jones launched a project called ‘Beauty Banks’; a nationwide collection of toiletries and cosmetics which are sent to shelters across the country for those who cannot afford to buy them.

Why donate products?

When looking at the statistics about poverty in the UK, the numbers surrounding hunger are clear. In the September of this year, The Guardian published an article which claimed that 14 million people in the UK are ‘living below the breadline’, with more than half of those people having been stuck in the same cycle of poverty for over a year.

At the same time, The Trussell Trust, a leading charity which aims to tackle UK hunger, saw its foodbanks provide over 600,000 emergency supplies to people in crisis between April and September 2018. This was a 13% increase on the same period in 2017, and the charity suggests foodbank use is only set to rise further during the winter months as the wait for benefit payments is elongated.

This then begs the question: when so many people in this country cannot afford to eat, why are people choosing to donate a seemingly superficial product like a makeup compact?

The evidence is more substantial than you think.

“Greater earning potential”

Research has suggested that access to cosmetics is not only linked to improved mental health, but connected to employability- something which the Welsh Minister for Lifelong Learning, Eluned Morgan, defines as ‘the most sustainable route out of poverty.’

“Women who wore cosmetics were perceived as having greater earning potential and more prestigious jobs”

In a recent study by Nash, Fieldman and Hussey, for example, it was found that women who wore cosmetics were not only believed to be healthier and more confident, but were perceived as having greater earning potential and more prestigious jobs by the onlookers who were evaluating them.

Another similar study found that people who struggled with depression expressed ‘enhanced self-evaluations’ and participated more frequently in social activities after they had been made up with cosmetics, suggesting that the value of a beauty product extends far beyond the superficial benefit.

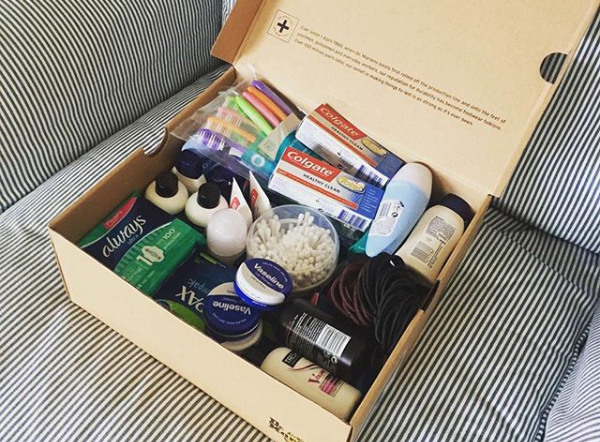

A box of toiletries ready to be sorted and dispensed to those in need, photo credit @thebeautybanks

“A Fundamental tool”

And, while clinical research shows clear evidence of a link between beauty products and employability, those with first hand experience of ‘beauty banks’ suggest that the correlation between access to toiletries and self esteem is undeniable.

Sian Elliott, a volunteer at Magor Baptist Church, South Wales, frequently donates toiletries and cosmetics through the UK charity Street Life Sarnies, and argues that while these products are often viewed as a luxury, they are also a fundamental tool for fostering a sense of wellbeing in people in poverty. This, she believes, in turn can improve the prospect of people getting into work. Sian explained,

“I am aware that there are many families who need to feed and clothe themselves and when food becomes a priority, toiletries and beauty products are last on the list.

“It seems incredible that some women are having to stay at home because they either can’t afford or don’t have access to sanitary products. This is wrong.

“I like to donate beauty products, as I think it is important for women’s self esteem and mental health. I feel better when I put my mascara on and smell nice, and I want all other women to be able to feel the same.”

Shannon Chittendon, 18, from Cardiff, similarly suggested that beauty bank resources should be considered as ‘key essentials’ after discussing her own experiences of poverty in a recent short film by the BBC. Shannon explained that access to makeup reversed the negative impact that poverty had on her self esteem and allowed her to partake in society, saying:

“It can help me go out, it can help me socialise, it can help me be a better person.

“Without makeup, I couldn’t present myself to society. I couldn’t show a strong individual, because I felt so low about my appearance.”

Makeup, Shannon explained, allowed her to reach her potential socially, and gain the strength to become an active member in society.

But what does this all suggest?

When a trip to your local supermarket leaves you viewing the donations that are ready to be sent to the foodbanks, the concept of a beauty product can seem like a superficial and unessential luxury.

Yet, both research and first hand experience indicates that access to these products not only lifts the self esteem of those in need, but improves employability prospects.

This, at a time when five percent of the Welsh population are unemployed, and a great 24.3 percent are ‘economically inactive’, suggests that toiletries and cosmetics are not simply a luxury, but a valuable political tool.

Beauty Banks: The Dos and Don’ts of donating

View this post on InstagramLoads of amazing donations! Thanks so much. ❤️❤️❤️ #beautybanks

A post shared by Beauty Banks (@thebeautybanks) on

The Dos

Sanitary products

Big brand supermarkets often sell these on offer, keep one packet for you, donate the other

photo credit @always_uk_ireland

Savlon / Germolene

This antiseptic essential is less than £2.00 in Superdrug

Lipsticks

Lipsticks can act as a pick me up, and can be found for under £5 in supermarkets like Morrisons

Hotel Minis

Travel size shower gels, shampoos, conditioners and body lotions are useful, and don’t have to be from a hotel- Sainsbury’s sell packs of Nivea travel essentials which include body wash and makeup wipes

Deodorants

These can be purchased for a pound or less in shops like Savers

deodorant and lipstick – two of the products that can easily be donated, photo credit @niveauk

The don’ts

While Beauty Banks are always grateful for donations, there are certain products they are not able to receive

Hairdye

FakeTan

Medicines

Anti-Ageing products

Perfume

Nail Polish

When you have gathered together your donations, you can visit Drop Point to find the nearest place to leave your donations, or find out how to post them

To cut out the middle man, sites like Easho pick, pack and deliver your donations direct to your chosen charity