Carry On film revival? Britain’s already got slapstick politics

There’s been some talk about a revival of the old Carry On film franchise, Britain’s most famous comedy film series. Unsurprisingly, the country’s most famous tabloid, The Sun newspaper, was enthusiastic at the prospect – although readers were concerned that modern versions might be too “politically correct”.

“Its like alcohol-free beer”, wrote one commenter, while another said that “as most of the original cast are dead it won’t feel like [a Carry On film] anyway”.

The Carry On series spanned 34 years from Carry On Sergeant in 1958 to the panned Carry on Columbus in 1992. In between, 29 films featuring the cream of UK comedy – featuring names such as Kenneth Williams, Sid James, Hattie Jacques and Barbara Windsor – became staples, known for risque double entendres and cheerful smuttiness.

Writing in The Guardian, Stuart Heritage recently described them as “dirt cheap films that highlight our collective national fear of sexual arousal”. I don’t disagree. Nor with his suggestion that their legacy provided those who use them as reference points with an imagined pre-EU Britain “that Leave voters see when they close their eyes”. They were sexist, racist, homophobic and xenophobic.

Yet, as Heritage’s Guardian colleague Fiona Sturges noted in her more equivocal reading of their endurance, “they also highlight much of what we have lost”. She was referring to the way the films highlighted the erosion of traditional social barriers in post World War II Britain and provided critiques of authority and class divisions.

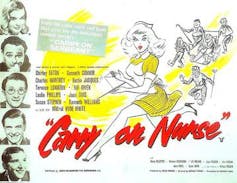

The earliest films: Carry on Sergeant (1958), Nurse (1959), Teacher (1959) and Constable (1960) are also noteworthy as commentaries on post-war British life as lived in relation to public service institutions: the army, the NHS, state schools and the police.

Like Sturges, I wouldn’t dismiss the Carry Ons from British cultural history, or histories of the British film industry. Profitably, they were even popular in America – Carry On Nurse especially was a barnstorming success with gross profits in the multiple millions.

Responding to a scathing review of Carry On Constable in The New Statesman in March 1960, its scriptwriter Norman Hudis addressed the the economic stakes for industry of the financial success of the series (in a piece that is sadly not available online). He believed that:

Money at the box-office … is what keeps cinemas open … I truly believe that it is films like this series which will enable the cinema, ultimately, to ‘Carry On’ – perhaps until the day when the standards of intellectual criticism become those of the general public.

Hudis thus defended their populism in economic terms. Meanwhile, in her recent piece, Sturges argued that “in catering to a working-class audience, the Carry On films offered cinema goers a chance to see a version of themselves on screen”.

Broad appeal

My analysis of data contained in the BFI Reuben Library showed how the early films were received by critics. One of the things that leaps out of those reviews are how many of the comic situations in the films are points of identification for ordinary cinema goers, for example, the depiction of national service in Carry On Sergeant: “Every young sweat doing his service will revel in it.”

Regarding the NHS, one reviewer wrote when the film came out: “If you’ve ever been in a hospital ward … Carry on Nurse will have you in stitches.” And regarding state schools a review read: “The staff-room discussions ring as nearly-true as they are meant to.”

A later turn towards parody of different film genres produced the best remembered and least derided films: Carry On Cleo (1964) – which was a send-up of big-budget ancient world historical epics – and Carry On Screaming (1966) – which lampooned horror, particularly the UK’s Hammer series.

Carry on Changing

Elsewhere the films continued to respond to UK social change. Carry on Abroad (1972) confronted the “Brits abroad” phenomenon emerging from spiking numbers of Britons taking international holidays in the 1970s, as this became affordable to those previously excluded from such travel by socio-economic circumstance.

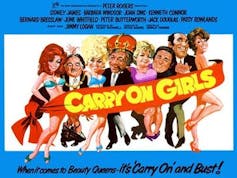

Spanish coastal destinations such as the Costa Brava, Blanca and Del Sol became – and remain – hugely popular with British visitors and migrants (ironically, given the political turmoil that has since accompanied inflammatory British discourse about EU migration). Carry On Girls (1973) depicted the corresponding impact of the proliferation of overseas package deals on the economies of British seaside towns that lost their attractiveness as holiday destinations.

Heritage says the films don’t stand up to scrutiny. I disagree. For example, most who have seen one will likely remember the sexual objectification and harassment of female nurses in the hospital-based films. But does everyone remember the nurses collectivising and intervening to protest this treatment in the denouement of Carry On Nurse? Their pushback culminates in the film’s most enduring visual gag, when Wilfred Hyde-White’s nurse-ogling colonel undergoes rectal examination with a daffodil.

As sexual abuse revenge plots go it’s not exactly The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, but it’s a moment of anti-patriarchy strike back that has been all too easily forgotten amid the lower-hanging fruit that some people have used to dismiss the film.

Cultural capital

A Carry On revival in these polarised times would be ill advised considering some of the sexist and racist attitudes with which the films are associated – some of which have been associated with the prime minister, Boris Johnson, or his reputed slapstick “Carry On” style. But the place of these films in British film history remains.

In 1999, the British Film Institute programmed “Carry on Chortling”, a season of Carry Ons at London’s National Film Theatre. This included a conference spearheaded by British cinema scholar Andy Medhurst who did important work contextualising the significance of the films, and was accompanied by the successful “Ooh! What a Carry On” exhibition at the Museum of the Moving Image.

The Carry Ons remain significant for how they responded to topical social issues. As Medhurst said: “If you want to find out what a culture thinks about itself, look at what it laughs at.”

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.