Facebook: it’s the advertising, stupid

Professor Leighton Andrews’ research seminar will focus upon the complex role of online advertising in the General Election and the dominant player, Facebook.

As we head to a UK general election, political parties in the UK are ramping up their spending on Facebook and its subsidiary Instagram.

UK election law on social media usage remains out of date. Parties and candidates have to report their social media spending but in many other respects social media electioneering remains largely unregulated, with proposals for reform languishing in the Cabinet Office.

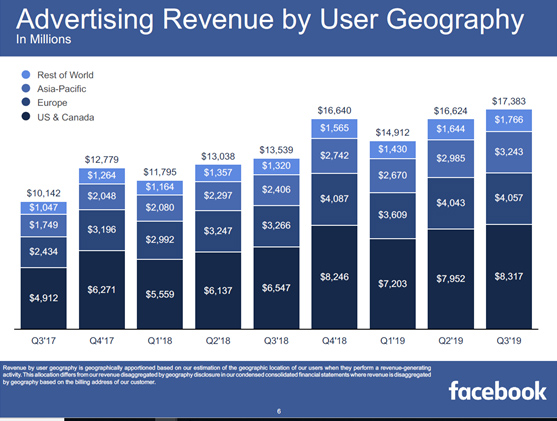

Advertising provides the overwhelming bulk of Facebook’s profits – over $48 billion in the first three financial quarters of 2019, and growing in all geographic markets.

Facebook’s ability to target users by microscopic demographic segment makes it appealing to advertisers of all kinds, from small businesses to large. But this micro-targeting has its downsides too. It undermines the concept of a public sphere in which political arguments can be argued out before all. It also opens out the opportunity for discriminatory advertising which breaches equality laws and has already got Facebook into trouble with the Housing and Urban Development Corporation and state attorneys in the United States.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) had warned that discriminatory practices outlawed in the 1960s and 1970s were now resurfacing in the digital era thanks to Facebook.

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner is investigating the practice of micro-targeting and whether it might contradict the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Earlier this year, the German competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt ruled that Facebook’s data collection practices were illegal, preventing it from combining data from different sources without permission. Facebook has challenged this, initailly successfully though further action is pending, in the German courts.

Facebook offers a free service in exchange for people’s data and their attention, which enables Facebook to charge advertisers for user engagement. Facebook has said it never sells users’ data, but the release of Facebook e-mails as a result of leaks of evidence from the Six4Three court case in California led the House of Commons DCMS Select Committee to say in 2019:

We consider that data transfer for value is Facebook’s business model and that Mark Zuckerberg’s statement that “we’ve never sold anyone’s data” is simply untrue.

Further emails released show that Facebook conceived a ‘dollars for data’ programme; and that Zuckerberg thought of Facebook as an information ‘bank’. These issues have been contested by Facebook.

Facebook’s advertising model has developed over time but only became turbo-charged in the period around its IPO in 2012. Facebook moved rapidly to work out how to link data from different sources, including from data brokers, in a way that was valuable to advertisers and also political campaigns.

Facebook advertising is based on the programmatic advertising model which has evolved over the last twenty years. Mark Zuckerberg told the Senate last year:

we basically calculate on – on our side which ads are going to be relevant for people, and we have an incentive to show people ads that are going to be relevant because we only get paid when it delivers a business result, and – and that’s how the system works….we get paid when the action of the advertiser wants to – to happen, happens.

The majority of online advertising is now sold through automated real-time ‘programmatic advertising’ or ‘behavioural targeting’.

Many advertisers may be bidding for access to an individual as they land on a website. An advertising exchange consists of Supply Side Platforms (SSP) and Demand Side Platforms (DSP). Publishers make their content available to advertising exchanges via the SSP. Advertisers decide which audiences they wish to target via the DSP. An individual visits a webpage. As it loads, information about the individual and the content of the page is gathered and reported back to the ad exchange. Algorithms process the information, and the advertiser is entered into an auction with other advertisers also bidding for the individual. Publishers get paid for the content shown on their sites. This all happens in milliseconds.

According to one former Facebook advertising manager, Facebook’s advertising system is a complex model that considers both the dollar value of each bid as well as how good a piece of clickbait (or view-bait, or comment-bait) the corresponding ad is. If Facebook’s model thinks your ad is 10 times more likely to engage a user than another company’s ad, then your effective bid at auction is considered 10 times higher than a company willing to pay the same dollar amount.

At the time of its Initial Public Offering in 2012, Facebook’s ‘like’ and ‘share’ buttons were on half of all US web-sites. The system also serves ads into Instagram, and now Facebook Messenger. Facebook ads are known as ‘promoted’ or ‘sponsored’ content – they will often include a note that your friends have liked a specific page or item and possibly ask you to like as well, which may mean content from that site subsequently appearing in your News Feed without being sponsored.

Facebook allows advertisers to micro-target an audience based on 98 or so characteristics including demographics, location, interests and behaviours, including purchasing and device usage. Facebook may use up to 52,000 different attributes to categorise Facebook users, provide some 29,000 categories on Facebook users to ad buyers, and hold 1,500 data points on average on non-Facebook users.

The real power centre of Facebook is its vertical integration as a social media network, a media distribution company, a media buying company, an advertising exchange or platform, an advertising agency, and a data analytics company; its horizontally integrated data exchanges between Facebook, WhatsApp, Messenger and Instagram; and the ability of advertisers to sell across the Facebook companies. Structural separation of Facebook’s advertising and editorial functions (e.g., in the News Feed) might be one solution.

It would be entirely possible for regulators to take action to restrict Facebook’s freedom of manoeuvre in a number of these areas; preventing it from operating its own advertising exchange; preventing the cross-company sharing of data or cross-selling of advertising; forcing its advertising operation to operate as an external buyer against competitive operations also granted access in a form of regulated unbundling and no doubt in other ways. Competition authorities in Australia, the U.K. and elsewhere have Facebook – and Google – advertising models under scrutiny.

Professor Leighton Andrews’ seminar is open to all Cardiff University students and staff, and will take place on Wednesday, 20 November 2019, at 16:00 in Room 1.10A, Two Central Square.