2020 Vision: Forecasts for the year ahead from Cardiff University School of Journalism, Media and Culture

Four small words; the future of journalism. What should we expect to see making a dent in our profession over the 12 months ahead?

What does social media have in store for a likely devious US Election campaign?

How can publishers rebuild bonds of trust with readers? Do new laws need to be passed to protect our democracy? And which cases in the courts could have an effect on the way journalists work?

These are among the questions we will see addressed in 2020 which, incidentally, is the 50th anniversary of Cardiff University School of Journalism, Media and Culture (JOMEC).

We don’t claim to have all the answers. If we did, we’d be down at the patent office/bookmakers and not typing our way through the Christmas holidays.

But our in-house international experts are continuously monitoring the significant developments in their respective fields and these are the areas they are focused on as 2019 becomes a memory.

Follow us on Twitter @CardiffJomec or at Facebook.com/CardiffJomec

“Finally, the public are getting wise to manipulated emotion.”

Professor Richard Sambrook, Director and Deputy Head of School

“There are two areas I hope people will pay more attention towards this year: value, and information inequality.

First value. As the economics of journalism continue to get harder we need to move away from easy clicks and the attention economy towards providing deeper value for users. I sense, finally, the public are getting wise to manipulated emotion to drive clicks and are seeking greater value from media in return for subscription or just engagement.

The sharing imperative on which much of social media has been built has been a reflection of shallow consumer interest but fails to reflect civic value of any kind. As more online sites move towards subscription out of business need, they will need to develop a richer proposition for users to open their wallets and to earn loyalty — and perhaps that will force open media to raise their game as well.

But one consequence may be information inequality. For those with the disposable income and with the motivation there is more and better information available than ever before.

But those who can’t afford several subscriptions or are not motivated to engage with the wider world are increasingly adrift in a social environment of fake news, abuse and clickbait sites designed to reap your data. Information haves and have nots represent a serious social and political problem which as yet no government is minded to address.”

“I anticipate the emergence of new outlets and voices in Scottish journalism”

Dr Francesca Sobande, lecturer in Digital Media Studies

Ipredict that the future of journalism will involve greater demand for forms of citizen and hyperlocal journalism, often aided by social media and user-generated content. People will continue to critique the so-called neutrality of high-profile media organisations and question whether journalism can ever be free from bias.

Given the current political landscape in the UK I anticipate the emergence of new outlets and voices in Scottish journalism which focus on the possibility of a second Independence Referendum in Scotland. In recent years, various media organisations have chosen to “pivot to video” and strip back the amount of written content that they produce but I believe that the future of journalism will include strengthened support of long-form, independent and investigative writing .

Although there is often an industry emphasis on speed and ensuring the quick production of content to keep pace with news and current affairs, the future may involve rising appreciation of “slow journalism” that does not succumb to the scrutiny of fact-checkers and which offers detailed deep-dives that are worth the wait.

“Do new laws need passing to protect democracy?”

Matt Walsh, Senior Lecturer in Journalism

That the U.S. Presidential election will be one of the dominant stories of 2020 is beyond doubt. As is the question of whether the social media platforms have done enough to prevent a repeat of the electoral interference and disinformation that marred the 2016 campaign.

There have been big changes since then. Facebook’s CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, has endured several uncomfortable appearances before Congress and the platform has been forced to make some big changes. Since 2016 it has announced a raft of changes, including to the algorithm of its news feed, increased transparency around advertising, and disruption of what it calls “coordinated inauthentic behaviour from Iran and Russia”.

Twitter has even gone as far as entirely banning paid political advertising. Facebook has not and has stood by its decision to avoid fact-checking political claims.

But as the UK’s general election has demonstrated suspicions regarding foreign influence have not gone away.

We should expect, then, a volatile and febrile atmosphere in the run-up to the election. Incumbents tend to do well, but Donald Trump is historically unpopular for a sitting U.S. President. The economy tends to be a key factor in vote-choice decision making and currently it remains in Trump’s favour. In 2016 Clinton won the popular vote, while Trump won the electoral college. And not forgetting the impeachment proceedings. That process looks set to dominate the news agenda through at least the opening months of 2020.

All in all, it looks like the election will be a tempting target for either state actors looking to cause confusion or fraudsters acting for profit. For the social media platforms, the question will be endlessly asked: “have they done enough or do new laws need passing to help protect democracy?”

“The future for magazines is basically going to be much more in your face”

Jane Bentley, Course director Magazine Journalism

The indie magazine sector, mostly in print, is quietly but solidly stealing a march and this will continue in 2020. Dual forces are shaping this progress.

First, audiences are getting sick of how much time they spend on screens so the concept of ‘JOMO’ (joy of missing out) is seeing eyeballs pulled back into high quality print products, with small circulations but specific points of view, in order to escape from the MSM (mainstream media) and generally have a reading experience that is more slowed down, unique and, frankly, cool.

Second, business models for magazines have had to be radically reinvented in the last decade, so now it’s commonplace for a title to have between four to eight revenue streams. This means if one model fails, as print advertising did, a title still has money coming in via other channels. This rapid adjustment has been challenging for all the mainstream, indie and business publishing sectors, but the indie market is also waking up to the idea that IRL (‘in real life’) events and opportunities to interact with readers help drive that ‘reader revenue’ concept and put money in the bank and drive loyalty.

The magazine as a measure of self-identity or being in a particular ‘club’ is therefore coming back. And we all know what happened in the ’80s when a proliferation of alternative culture, music and lifestyle titles eventually came to shape what we now know as the consumer lifestyle market. Even The Face came back in 2019 (and sold out immediately) which tells you that another cultural revolution is bubbling away. Only this time it will serve much smaller audiences. The ‘mass market’ is over.

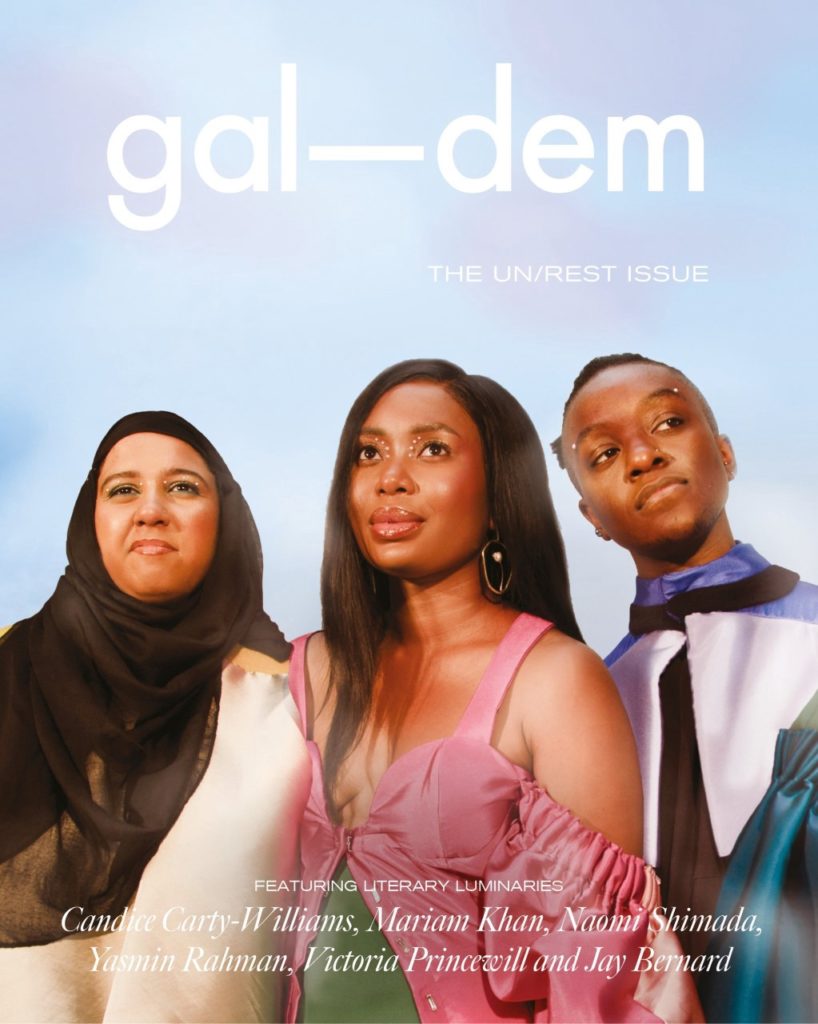

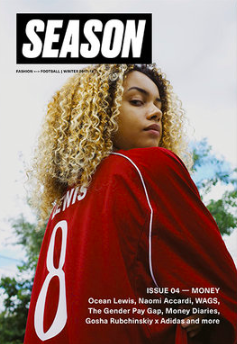

Diversity is another massive area where indie mags are making gains while mainstream consumer titles and publishers simply struggle to catch up, as they are just not on the same page. The rise and rise of gal-dem, a website and print magazine by and for women and non-binary people of colour; the female footie-fan mag Season Zine; or Anxy, which covers mental health issues, are ones to watch. So expect even more niche titles springing up that speak to very specific audiences that have been simply ignored by most media till now.

Look at Vogue UK still struggling to find its way under Enninful’s new, more inclusive direction. There are some promising developments in sustainability coming from Condé Nast in 2020 — but will it be too little too late?

There’s also going to be more publisher sales and consolidation, with Future’s purchase of TI Media at the tail-end of 2019 an indicator of this. The CMA can hardly object any more to large publishers with similar interests joining forces when their combined size commercially is still only a drop in the ocean compared to Facebook, Amazon and Google.

More axes will fall during these consolidations, with inevitable print closures and staff losses. But as the various revenue models are examined for growth potential, tricks like ecommerce will come to dominate and even resurrect some titles, plus launch new ones.

The mainstream publishers like Bauer, Hearst and Condé Nast are already looking to some of the successful indie products and social media influencers making waves and learning lessons. Therefore, I predict a much more emboldened editorial landscape in 2020.

This will mean more innovative combinations of stunning imagery and storytelling, which is what magazines do best. More commissioning of quality visuals in print and on digital platforms will enable brands to stand out. I expect more investment in illustration, photography and immersive media in order to elevate standout storytelling that’s unique and shareable. Check out PinkNews on Snapchat, for example.

Grazia editor Hattie Brett is already championing more political coverage and campaigning in its pages. Recent reader research showed Grazia’s professional, female readers believe the world is a confusing and scary place right now, and while they are prepared to take action, they need to be better informed than ever before. “It is evident that the role of magazine brands is evolving,” the research states. “In a sea of digital content Grazia offers curated, trusted editorial and inspiration that cuts through the noise. Magazine brands go beyond the rolling scroll, offering more considered, reflective opinion on subjects that face this audience in this new normal.”

And it’s about time beautifully curated, provocative, original storytelling was back, serving up brain food rather than braindead scrolling. The future for magazines is basically going to be much more in your face.

“Editors who see their roles as community co-ordinators and co-creators are going to be the ones who unlock new opportunities for growth.”

Matt Swaine, Course Director, MA International Journalism

Asa former magazine editor, I’ve always been interested in the role that readers can play in the publications they read.

The internet and mobile technology allows them to create far more content that can be shared instantly and easily. I don’t think we are going to unleash an era of full-on citizen journalism, but I do think we are going to see more titles experimenting with ways that they can become not just content providers but community co-ordinators, bringing their readers closer to the editorial process.

And building community can be incredibly potent. On specialist publications shared enthusiasm and passion for a subject can engage readers more deeply and unlock new revenue streams. It can even increase print sales, as my former colleagues on Country Walking have shown.

Shared ideals and the opportunity to get more involved with editorial decisions can deliver new ways to fund journalism, as Guardian membership schemes have shown at a national level and titles like the Bristol Cable are proving locally.

Editors who see their role as one of community co-ordinators and co-creators are going to be the ones who unlock new opportunities for growth and find new ways to fund genuinely important content.

“Documentaries have an increasingly important role to play in 2020 and beyond”

Dr Janet Harris, Director of Digital Documentaries

What defines documentary is its relationship with the truth. Documentarians acknowledge and grapple with the constructed nature of truth, and this recognition means that documentaries can not only investigate it deeply, but also fight for it.

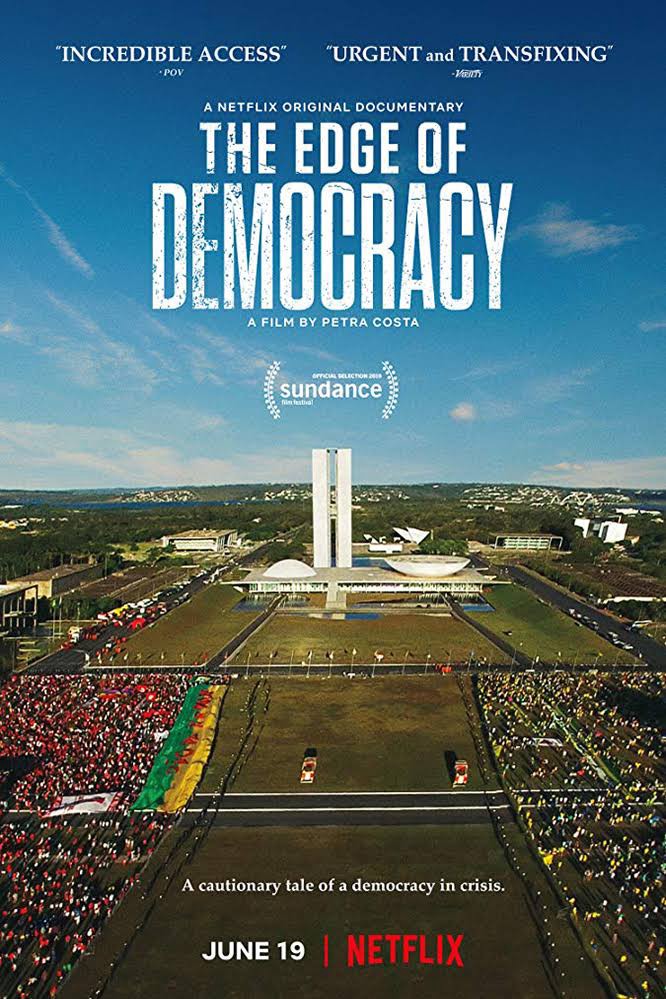

2020 Oscar nominated documentaries such as The Great Hack (Jehane Noujaim), an examination of Cambridge Analytica and its impact of global elections; The Edge of Democracy, (Petra Costa) which looks at the rise of the far right in Brazil, and The Dissident (Bryan Fogel) about the murder of Khashoggi, investigate human behaviour, its association with structures of power, and the search for a truth.

This search and a close collaboration between the director and the people on camera, demonstrated in The Cave (Feras Fayyad), is a quality that seems present in many recent documentaries and perhaps a mark of future documentaries. As journalism struggles with fake news and changing markets, documentaries have an increasingly important role to play in 2020 and beyond.

“You can only dance between the raindrops for so long before your black turtle neck gets wet.”

Gavin Allen, Digital Journalism Lecturer

“If you can’t see the angles no more, you’re in trouble, baby,” says Carlito Brigante (Al Pacino).

In Brian De Palma’s 1993 gangster classic Carlito’s Way it doesn’t end well for the sharp cookie who thought he had all his geometry sorted.

And that’s the bizarre analogy I’m applying to social media and the platforms — where change may finally be coming.

Whether that change is led by government intervention and break-up (the US anti-trust investigations), the platforms themselves trying to control said regulation with limited reforms or even the rapid growth of emerging new players (TikTok) to unbalance the current giants’ dominance, one thing is certain — we’re closer than ever to that breach point.

You can only dance between the raindrops for so long before your black turtle neck gets wet.

Facebook and Donald Trump currently have a fireside relationship — and we all know he’s obsessed with tweeting. However, if a change is made in the White House in November we may suddenly see a cleared path towards holding the platforms accountable over some key issues. Where the US leads the Western world will follow. We know strong intent towards regulation exists across international boundaries — with moves against Google in Europe and in the UK via The Cairncross Review recommendations.

Yet darker alleyways need navigating if the platforms want to escape 2020 unscathed.

Facebook is being sued by one of its former moderators, Chris Gray, who alleges his work viewing up to 1,000 pieces of flagged content per night caused him to suffer Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

The moderation issue is a potential powderkeg and Gray’s case, were he to win, could light the touchpaper on a significant class action. Landing a punch on Facebook under workplace Health and Safety regulation might sound a little like getting Al Capone on tax evasion, but here’s the point.

Might users who unwittingly see unmoderated content — such as whatever proves to be the next hideous iteration of the live-streamed Christchurch massacre — be similarly traumatised and seek legal redress? Gray’s case also opens the way to legal action from the platforms’ user-base — and that might be more significant.

None of the above issues alone will disrupt the power structure.

But pressure is now coming from all angles and it may be an unexpected knife that inflicts the deepest wound.

“The creative storyteller who seeks solutions and comes with a different, if not original perspective”

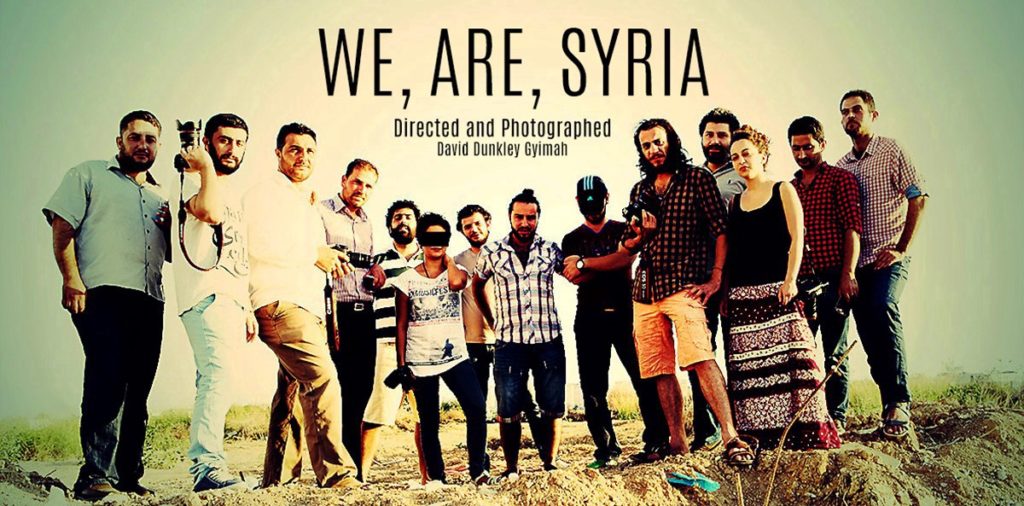

Dr. David Dunkley Gyimah, Emerging Journalism & co-investigator

Predictions can often follow an extrapolated trend of commercial-tech interests in which players gather around tech to support burgeoning journalism forms e.g. VR, Mobile, AI (read Carolyn Marvin’s When Technologies were New).

They have purpose. The noise too they generate (shiny object syndrome) can easily drown out the multiple attention deeply warranted in journalism as politics and nationalism corrode society. Cognitive reflection is required. A conscious debate, local and international, between tech and journalism is needed. Journalism has found no conclusive answers yet.

Politicians have zealously re-discovered the seam to game populations; lies now elicit a chuckle and a shrug amongst a huge swathe of the electorate; the surrealists have found and dug their heels into journalism. AI will save us all, we’re told. This is where we are.

Imagine if Christopher Nolan, or Spielberg did journalism? What might they do differently, which was one of the questions behind cinema journalism. 2019’s well deserved multiple winner Waad Al-Kateab’s For Sama, as I have written previously is an example of this rejuvenated form. There are others. Innovative, camera-agnostic, creative storytellers will continue to untether their moorings from past formulas.

What if more people that looked liked me, your sister (diversity)etc. were in positions to contribute in impactful ways to bricks and mortar journalism? Having a different perspective isn’t a bolt-on to innovation, let alone journalism. It’s what creativity thrives on; it’s how journalism should function.

What would it take for journalism to invest more in understanding the pragmatics of psychology, depth manipulation and behavioural economics to spot alt right traps and dead cats? Celebrated US journalist Walter Lipmann flagged up our current woes in the 1920s.

There exists a long tail of practitioners now exploring Codiprops:

- Collaborations — greater crossing of disciplines

- Diversity as a solution involving different approaches (e.g. Marcus Ryder)

- Problem finding via design thinking to solve stories in journalism

- Psychologies and behaviour science in presentations

- Storytelling, critical and creative e.g. Adam Westbrook

There’s what the industry follows as a convention in the status quo, and what could be moments or reckoning that bring about radical progressive changes, inviting fresh ways of doing things.

Could 2020 be synonymous with great vision? Momentous change, from incremental shifts, would come about in the 1890s in Art, in the 1900s in literature and physics, and 1930s/60s in cinema. The US’s pending election will be a barometer for “if we keep on doing what we’ve been doing, we’ll keep on getting what we got”. The change is there to grasp, but that means, “You have to start looking at the world in a new way” (quote from Tenet, Christopher Nolan’s next film).

“Closed Facebook groups are building membership numbers specialist publications would be proud of.”

Tim Holmes, Associate Director PGT

Closed groups on Facebook will continue to make inroads into the specialist magazine market, but only carefully moderated groups will thrive.

For example, British Motorcycle Mechanics has nearly 15,000 members, which would be a tidy print circulation figure at this level, each one of whom has been vetted by the administrator.

Vetting means bots and bad actors are excluded, and the admin is not averse to shutting down threads that get caustic. Members include many of the experts whose wisdom print magazines such as Classic Bike draw on, as well as the people running businesses that (used to) advertise in print. Topics are constantly generated by members (who come from literally all around the world), there is a freely available archive of how-to documents and a lot of nice photography. It’s like an always-on magazine and generates a strong feeling of community.

Important democratic gaps at local level will increasingly be filled by local and hyperlocal Facebook groups. The main group for my city is lively, varied and politically pluralist. The leader of the council frequently joins in the threads and can be held to account by members, with varying degrees of success (just like mainstream media). The group is also an important point of contact between permanent residents and the large but transient number of students in the city, at least as represented by a university co-ordinator. Interestingly, the hyperlocal group for my locality is much less politically diverse — I’m sure there is some interesting research to be done around that.

Podcasts will develop shorter forms. The norm of circa 30 minutes is a considerable commitment that works well for longer bus, train or car journeys but I predict there are plenty of people who would like something shorter and less committing.

“Worrying example of a wealthy person singling out an individual journalist”

Sandra Loy, lecturer in Media Law

I’m not the only journalist who’ll be keeping a jittery eye on what happens next in the Carole Cadwalladr v Arron Banks case. The investigative journalist is being sued by the businessman and pro-Brexiteer over the meaning of words in two tweets and two public talks.

This isn’t about a big media organisation finding itself in a costly defamation case. Cadwalladr alone is in the firing line. It’s personal. The very fact that the action is taking place has been called a “worrying example of a wealthy person singling out an individual journalist and using the law to stifle legitimate debate and silence public interest journalism”.

It’s also been described as an attack on all journalists’ ability to report on how our elections are funded. A preliminary High Court ruling in December has been taken by some to have gone the defendant’s way. 1–0 to Cadwalladr. But libel trials are notoriously difficult to predict.

The stage is set for a fascinating trial, the outcome of which could well have an impact on how many journalists operate. Without wishing to sound flippant, am I wrong to feel disappointed that Meryl Streep is too old to play Cadwalladr in the movie some day?

“Photojournalism’s 2020 Vision”

Professor Stuart Allan, Head of School

With allegations of ‘fake news’ continuing to spark acrimony across the breadth of public life, photojournalism’s privileged status in the pictorial mediation of the world around us is increasingly open to question — indeed, some would say it is poised to unravel in the weary, cynical swirl of ‘alternative facts’ associated with a ‘post-truth’ society. Accordingly, this blog post aims to encourage efforts to revitalise the visual authority of the news photograph — and with it the photojournalist’s claim to reportorial integrity — in the search for positive ways forward.

In considering several factors at stake, it is necessary to first recognise the harrowing personal risks confronting photographers in crisis situations — professionals and ordinary citizens alike — striving to capture and record imagery of newsworthy significance. Acutely aware they may well be deliberately targeted in warzones, imprisoned for documenting human rights abuses or, closer to home, forced to cope with intimidation, legal censure or fear of arrest, she or he will likely set forth an impassioned defence for visual truth-telling in the public interest. Placing themselves in harm’s way to bear witness is a demand consistent with their role, particularly when media freedoms are being violated.

Turning to more everyday news environments, photojournalism’s once sharply cast priorities are blurring under intense commercial pressures, its social responsibilities in danger of succumbing to the chimerical charms of click-bait infotainment. To the extent an ethical commitment to dispassionate relay is deemed to be an impossible achievement, the professional may well stand accused of imposing a selective, self-interested narrative to advance a prefigured editorial agenda. Impartiality will be derided as a contrivance in the eyes of some, a deceptive pretence which fares badly when compared with the raw honesty of the smartphone-equipped amateur who happens to be on the scene.

At the same time, we are all too aware of how the shifting, uneven imperatives of a ‘photo-saturated’ lifeworld engenders its own perils, with the glut of compromised images streaming through social media feeds inviting a corrosive scepticism regarding what can be verified as credible or authentic. Familiar platitudes that ‘seeing is believing’ because ‘the camera never lies’ seem anachronistic, if not touchingly naïve, even when the ‘acceptable limits of Photoshop’ are being respected rather than transgressed. Meanwhile the algorithms driving sharing platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Snapchat, Pinterest or Tumblr are inscribing new visual sensibilities, the participatory logics of which embedding an ethos of acquiescent consumerism over active citizenship.

Identifying these and related factors is the first step in reversing them. Quality journalism demands proper investment, yet most news organisations deny it the resources required to foster cultures of experimentation and innovation. This when public trust in ‘mainstream’ reporting appeared to be reaching a crisis point even before the scourge of ‘fake news’ rhetoric began contaminating perceptions. Photojournalism has not been immune from sustained criticism, making it all the more important lessons are learned (the partisan manipulation of visuals by the popular press during the recent national election campaign being a case in point).

Now is the time to create alternative conditions of possibility for new forms of dialogue and debate over how best to recalibrate photojournalism for a digital age. We need evidence-led analyses bringing together diverse, challenging perspectives to inspire progressive change. To rethink longstanding responsibilities will not be easy, particularly when engaging publics less inclined to believe photojournalism is fit for purpose than previous generations, but all the more necessary for its future viability in 2020 and beyond.