Cap and Gown – Cardiff University’s student newspaper in WW1

Posted by: Dr John Jewell

Gair Rhydd (Free Word) is the newspaper of Cardiff University’s students with a potential audience of nearly 29,000 readers all expecting to read a paper which can cover local and international news, provide incisive commentary on a range of social and political issues and cater for the lighter side of college life.

It was partly the success of Gair Rhydd and the realities of life as a modern student, which made me consider, as we approached the centenary of the beginning of World War One, how the Cardiff student of 100 years ago communicated and dealt with the life changing events which began in 1914.

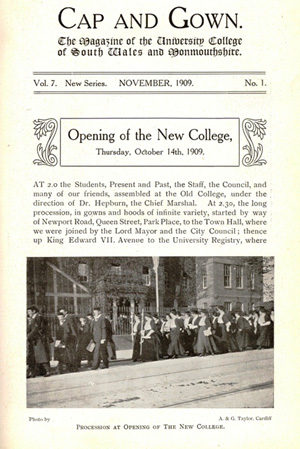

For scholars of a century ago Gair Rhydd was Cap and Gown – the magazine of the university college of South Wales and Monmouthshire (As Cardiff University was then known).

The first edition I looked at was from May 1914 some three months before the outbreak of war. And, apart from a brief mention of the lack of an officer training corps in Cardiff, there is no mention of the prospect of encroaching war. Indeed, there is, to my eyes at least, an air of whimsy and celebration about the whole edition which makes the knowledge of what is to come even more affecting. The editorial could have been written yesterday: ‘everyone who has taken even the smallest interest in the life of the college cannot but look back on his or her sojourn here as one of the happiest periods of life and it is natural to suppose that everyone will want to keep in touch with the institution that has afforded such happiness.’

And it’s this 21st century tone which most striking. Consider these lines from the poem,

‘Behold I am not one who goes to lectures’:

I am not one who greatly cares for experience, soap…or a graduated income tax.

The coercion of Ulster, Lloyd George, Mexico…or College conversaziones

For none of these do I care…

Myself only do I sing

Me, envied, popular, tremendous, colossal, titanic, stupendous

Ego! Moi-Meme! ME.

A terrific satire lampooning the narcissistic tendencies of privileged youth? Probably, but one can’t entirely discount the possibility that Cardiff was nurturing its own prototype Morrissey.

Elsewhere, there are essays on nature and art, a genuinely funny article on the quality of student ‘digs’, letters on suggested examination reform and a jokes, which, with a little modernising, you could imagine being told in the the union bars of today:

Scene: A professor’s private room

Time: April 16th

Student: I am very sorry, sir, that I could not get back on the 14th, but-

Prof: So you had two more days of grace did you?

Student: Well, sir, not exactly two more days of Grace; her name was Phyllis.

I was a little surprised by the lack of reference to rising tensions in Europe , but the fact that the issues which concerned, or didn’t bother, the student body of a 100 years ago are replicated so similarly today was oddly reassuring.

How would things change by the next issue of December 1914, the war being underway for 4 months?

War is present from the beginning now as the reader is presented with a picture of a Dan Jeffreys – the elected president of college who has relinquished his role because ‘when the choice had to be made between the robes of office and the khaki uniform, he chose the latter’. Later in the magazine we are told that the editor elect, Mr George Thomas, had also decided to ‘cast aside the academic robe for a time and put on the uniform of the British soldier’. The magazine, we are told is, ‘proud of him – as soldier and a gentleman.’

If this manner is reverential or matter of fact I was not prepared for what came next. It’s a ‘War Guyde’ written by an anonymous writer who nevertheless has ‘unrivalled military experience, having been the owner of a pair of military hairbrushes for many years.’

The tone of the guide is mocking and satirical. It was rather shocking to see such open scorn and criticism of how the war was being presented. The reader is told that the war is a, ‘fierce struggle’ and ‘the most terrible cataclysm that has alarmed the world for centuries’. Indeed, the German crown prince has been ‘killed on 7 different occasions’, ‘besides being fatally wounded 23 times.’

But not for this student the deferential attitude to war poetry that shapes our attitudes to WW1 nowadays: we are told that, and remember this is Cap and Gown from 1914, ‘no fewer than 17, 643, 279 war poems have appeared in newspapers and periodical since the war commenced’.

Yes, the article states,’this is a terrible war – but unfortunately its one of the best we have at the moment.’

Newspapers are the subject of much derision – ‘possibly more terrible than the war are its results: among them, the newspaper accounts. The newspapers hash up the same news day after day and you decide to give up taking any until you remember how useful it is as a firelighter.’ This is truly remarkable given the existence of the Defence of the Realm Act which forbade the publication of material expressing criticism of the war effort.

But the war had truly come to University college of South Wales and Monmouthshire in December 1914. There appears a list of students past and present who have enlisted for the war…but, the point is made, ‘though no effort has been spared, it has been difficult to find the names of past students who have joined the colours’. Even with this caveat there are 129 names listed. This is December and war broke out in August.

We learn of Wilf Watkins once a lecture of education who, having enlisted, went to France and was wounded in two places by shrapnel. Cap and Gown reports, ‘he is now fortunately on the high road to recovery, so much so in fact that he has taken unto himself a wife’. Undeterred by his experiences, ‘when fully recovered he hopes gain to take his place in the regiment’.

Elsewhere we learn of the college staff, ‘many of are now giving the whole or part of their time to work in connexion with the army. Here is Professor Barbier who has ‘no less than six members of his family serving with the French army.’

The college staff who stayed behind are supportive and speak in the language of the age. An address by Professor Norwood to students who would become ministers in the Church in Wales is printed in full. He is no doubt about Britain or its response to Germany. He says

‘We have heard much in the past about the British spirit….now in this supreme hour it has shone forth magnificently. There has come a fearful crisis, a loud appeal, and a glorious response. And with it all how little heady jingoism or mere acrimony…’

And amidst all this is a pithy epistle to the ‘freshers’ from a seasoned undergrad, the message of which seems to predate the summer of love and the hippy 60’s by some 50 years. The thrust of the advice can be can be adequately described thus:’ be ye not troubled, take things as they come. Above all things, be cool’.

Be cool!

Of final poignancy is an article by a member of the University’s and Public Schools brigade who writes of his time billeted in Essex with a 1,000 (200 from Cardiff) other men. Whilst not yet fully one of the ‘tommies’ the correspondent writes of the, ‘thrilling military atmosphere’. There is an air of melancholy about the idyllic life described, though and acceptance that their fate is out of the hands of these young men. The correspondent writes, ‘we have been here eight weeks and as to our future know nothing, or next to nothing.’

I was moved by the simple prophecy of these lines, ‘for our subsequent fortunes we must politely refer you to the newspapers, perhaps the casualty lists in particular’.

It was not even 1915.