Have 24-hour TV news channels had their day?

Posted By: Richard Sambrook and Sean McGuire

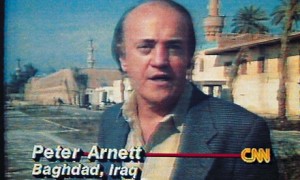

It’s January 1991. Peter Arnett is reporting from the Al-Rashid hotel in Baghdad as the first air strikes of the Gulf war hit the Iraqi capital. He’s live on CNN. Audiences around the world are gripped. The 24-hour news channel has come of age.

Fast forward to January 2011. Tahrir Square, Egypt. Citizen journalism ensures that pictures of demonstrations and the resulting crackdown are beamed directly to a global audience.

The next year, 8 million people tune in live to YouTube to watch Felix Baumgartner jump from outer space. Many times that audience log in to watch it over the next few days. Spin on to April 2013 and the Boston marathon bombings. CNN stumbles in front of a huge and anxious audience claiming an arrest had been made when it hadn’t. Live blogging – with its speed, transparency of sources, and pared-down format – comes into its own.

The past two decades have seen a revolution in every aspect of the media industry – technological change has enabled consumers to develop sophisticated and subtle patterns of behaviour, constantly being updated from a variety of sources. Cable news established the 24-hour news habit, but today social media and mobile phones fulfil the instant news needs of consumers better than any TV channel can.

Yet around the world hundreds of millions of dollars continue to be invested each year in news networks. Is this money well spent? Or has the time come to rethink the TV news business? Were live channels simply the product of the satellite age which is now all but over?

Did 24-hour news have its moment in the sun – quite literally – in the deserts of Kuwait?

Whose needs are news channels meeting?

24-hour TV news broke the audience away from the daily news cycle, focused on a flagship primetime newscast. But should linear satellite channels still be the focus of so much attention in the interactive internet age? They don’t quite give us news when we want it – we often have to wait 15 or 30 minutes for the story to come around – so it’s news-not-quite-on-demand. If we want it now, we will go online and get it instantly.

Twitter – and increasingly live blogs of breaking news events – consistently beat 24-hour TV channels. And on those defining moments that bring the nation together the multichannel broadcasters will, and regularly do, clear their main mass-audience channels.

So that makes a news channel perfect for those quite big, but not really big, stories for people who want information quite fast – but not immediately. By anyone’s judgment, that’s a small (and slightly weird) segment. Beyond that, it’s great for people stranded in hotel rooms, office foyers or trading floors. But even that doesn’t provide a huge audience – and probably not one in need of an entire network.

Rolling news imposes too many costs on the system

The infrastructure behind a 24-hour news channel is impressive – and formidably expensive. A studio, with two anchors and a steady stream of contributors and guests who all have to be booked and taxied to the studio. Behind them a shift system of producers, graphics designers, crews and editors. Reporters and camera crews around the clock. And underpinning them, continually open satellite links, transponders and digital terrestrial TV channels.

All in all, that’s an incremental cost of £40m to £60m each year.

Vamping dish monkeys can’t gather news

The biggest cost comes from having created a machine that has to be fed. Every 15 minutes we go back to our reporter in the field for an update on what’s happened since the last time we visited them. Most of the time the answer is “nothing”.

But even if something had happened, the chances are we wouldn’t get to hear about it – as all they’ve done is stand in front of the camera waiting to go live. “Dish monkeys” as they are unflatteringly known. To actually go and get the news they’ll need to send – and pay for – a second crew.

Newsgathering becomes a sausage machine, dedicated to filling airtime. Hours a day are spent on live feeds waiting for something, anything, to happen. “Vamping” it’s called in the business. A correspondent talking to fill empty airtime until the press conference or event begins. The editor can’t risk broadcasting a different report or going live somewhere else in case he misses the start and a rival channel can claim to be “first”.

24-hour channels warp news value judgments

The need to fill airtime – and particularly the need to be seen to be live – means that in the heat of the moment questionable editorial judgments can be made.

Everything seems to be “breaking news”. In the last 12 months we’ve seen the BBC showing live pictures of an empty courtroom in the US, eagerly anticipating the sentencing of already convicted kidnapper Ariel Castro – a story of interest to few if any in the UK.

In the US itself, we’ve had terrible misjudgments in the aftermath of both the Boston marathon bombing and the navy yard shooting. Al-Jazeera America – keen to make impact in the US market – follows the lead of the other news channels and vamps for 20 minutes or more until the president’s press conference begins.

When a presenter feels compelled to say “Plenty more to come, none of it news. But that won’t stop us” (BBC News’s Simon McCoy, waiting for the royal birth ), then there really is a problem.

The world has moved on

The genesis behind the news channel was the advent of global satellite links. News could be transmitted from anywhere, repackaged and then delivered to people’s homes. When CNN launched in the 1980s the live capability of a satellite network was breathtaking and transformative.

Now, technological developments mean that for the most part the internet has replaced satellite links for capturing and distributing the news. At the same time, consumers have broadband links to home, office, tablet and phone. Yet the industry remains wedded to the idea of a single, linear channel. Audiences have never been convinced. Viewing figures for news channels have always been low – spiking when a big event happens. The justification for broadcasters was to have a rolling spine of coverage that could be turned to at moments of need. Increasingly, however, we turn to the internet.

News channels prize being first – a race that they can’t win, and nobody else cares about. “Did we beat CNN?” is a phrase often heard in a newsroom. But in the digital age social media will always win the race to be first (if not always the race to be right). And who, other than the inhabitants of newsrooms, is watching enough news channels simultaneously to know who was first anyway? Those 30 seconds might be important for commodity traders – but for news audiences?

In today’s media environment any broadcaster is first for minutes at most – by which time Twitter or the competition will have caught up. Being first – the primary criterion for 24-hour news channels – is increasingly the least interesting and effective value they offer.

What is ‘live’ anyway?

What do we mean – and what do consumers expect – from “live”? Some news events are clearly reported truly live – the second plane hitting WTC2 on 9/11 or Sky News’s Alex Crawford broadcasting live as she entered Tripoli with the rebels. But beyond this, very few news events are covered as they happen. Press conferences are edited and reported; two-ways with reporters often cut away to pre-recorded package where the real storytelling takes place.

News editors have conflated on-demand with live – and in doing so have added costs for very little audience benefit.

Live pictures only rarely tell a thousand words

Television news can be powerful, moving and informative. It can, in the space of a few minutes, change the outlook of an entire nation. Walter Cronkite on Vietnam; Michael Buerk on Ethiopia.

Yet the number of stories that are conveyed by live “as it happens” pictures is vanishingly small. Many stories – the economy, climate change – aren’t best served by pictures; others (inside Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan or Zimbabwe) often don’t have pictures available until days after the event; many more work better with a well crafted, tightly edited package rather than a live feed.

There is some great journalism on the news networks – but seldom live and often in spite of the platform, not because of it.

News channels have their own narrow agenda

Outside of big breaking news, one of the lost opportunities of all that airtime is coverage of under-reported places or issues or providing more analysis or depth. The reason is that all the resources are tied up, waiting to “go live” on the same narrow agenda as everyone else.

Global news channels have their own parallel world of timeless, rootless programmes that work as well at 2am in an airport as at 2pm in a jet-lagged hotel suite.

Their agenda strains to find common ground for a global audience so is full of pictures of middle-aged men getting in and out of cars at international summits. Plus the live correspondent two-way confirming that although it’s a very important event, nothing much has happened.

Global news channels are the old ‘new imperialism’

Most of the rash of global news channels that have been launched in the past 10 years are in some way state-backed and – although this is frequently denied – are there to reflect a particular set of values to the world.

These channels seldom if ever make money – they are not commercial propositions. It’s about “soft power” – which at least is a purpose. China has invested more than $7bn in international broadcasting and talks of laying “cornerstones to underpin a de-Americanised world”.

Exposing the world to our political and social values may be the strongest justification for global news channels. But in the meantime much of the audience, including in developing countries, are looking at their mobile phones and posting to Facebook. Those are the new arenas for global influence.

News channels feed partisanship and the echochamber

This is particularly true in the US – where TV is unregulated – and a consequence of the undeniable success of Fox News. Talkshows and argument fill the airtime more cheaply than on the ground newsgathering. To create impact and get noticed both hosts and argument become more partisan and more extreme.

People choose the channel that agrees with their views and become less exposed to other viewpoints – encouraging partisanship, political polarisation and a political echochamber that ill serves open democratic debate.

The problem isn’t the consumer

At heart, the problem is a closed, linear technology failing to keep pace with the growing on-demand, interactive expectations of the public.

News channels suffer from low audiences – at times vanishingly small. These audiences were boosted by a switch to multichannel and digital TV; now they are at best flat and in many cases declining.

This isn’t a sign of a lack of interest in news. In every major market, well over 80% of consumers read, watch or listen to the news each day. But they are becoming increasingly discerning – using multiple sources to create their own news agenda, many of them online.

So what’s the answer?

A news service for the next two decades

The legacy of 24-hour news channels is holding back broadcasters in adapting to the potential of the digital age. If you gave a digital news operation even a fraction of the tens of millions of pounds currently spent annually on a news channel, just think of what you could achieve.

A truly news-on-demand service, with no heritage – not reusing TV material, nor reusing print – could be genuinely ground-breaking, reconstructing a news operation and creating a new relationship with audiences and consumers.

This is starting to be recognised in the US:

• CNN’s Jeff Zucker has planned major changes recognising there is “not enough news” to fill a news channel

• CBS is reported to be developing an online streamed news channel, separate from broadcast channels

• Al-Jazeera in the US has developed AJ+ as an online-only source of video news

• Yahoo has recruited one of America’s biggest news names in Katie Couric to “anchor” their news home page

• Digital companies such as Vice and Buzzfeed are recruiting significant numbers of foreign correspondents and opening global bureaux – built around the web, not satellites

Elsewhere there are fewer signs of experimenting with continuous TV news. ITV, unhindered by a news channel, reconfigured their website into a live stream that is both innovative and regularly beats the competition. The BBC’s director of news, James Harding, has acknowledged the need for more R&D by creating a “Newslabs” team looking at data and visual journalism. But perhaps the industry needs a bolder vision.

What might a reconfigured on-demand news service look like?

Integrating TV feeds into the web (and remember all TVs will soon be internet connected) could save cost, free resources and provide improved speed and depth of coverage. No need for a channel, or satellite space, or a DTT slot. More journalists gathering news, fewer filling space.

Give consumers what they want, as much as they want, when they want it

A menu of on-demand packages that can be assembled into a personalised bulletin, with the ability to go into as much depth as you want, accessing comment, pulling in charts, data and analysis from specialist sources as part of the experience. The bulletin waiting for you on any device, learning from you as you go, or interrupting you with the things you really need to know about right now. Look, for example, at Watchup TV aggregating and curating news video across the web.

Let newsgathering gather news

Return newsgathering to what is says on the tin – a service that goes out to speak to people, investigates, considers and then files packages as needed, with updates and commentary, freed of the need to fill empty space. When something happens, or new information comes to light, a new story can be generated. A package can be updated and be ready to go as soon as the consumer needs it.

Spend money on what matters – and ignore what doesn’t

It’s not two bodies in a studio waiting, hoping for something, anything to happen, or a miserable guy under an umbrella filling empty time. It’s both far more, and far less, than that.

Satellite news channels have played a hugely important role in the development of 24-hour news and information over the last 30 years. But technology, and consumers, have moved on. Might 2014 be the year we recognise that, like the emperor’s new clothes in Hans Christian Andersen’s tale, news channels are not all they pretend to be?

Richard Sambrook is professor of journalism at Cardiff University and former director of BBC Global News; Sean McGuire is managing director of media consultants Oliver & Ohlbaum and a former BBC News head of strategy

This blog was originally posted in The Guardian