Local journalism in crisis.

In October 2015, at a cost of £220m, Trinity Mirror, the parent company of Mirror newspapers and the Sunday People, took complete control of Local World – publisher of around 100 local newspaper titles. The purchase has worked out well for the newspaper group – This is Money reported that the company’s share price rose 7% to 80.0p on August 1 following the company’s announcement of a 42% increase in profits for the half year to £66.9m on revenues of £374.7m.

Trinity Mirror’s chief executive, Simon Fox, told the BBC that the acquisition of Local World brought with it sales and profits across a significant number of respected titles. The company’s concentration, he said, was on digital, adding:

There may well be a time when there are no papers … I hope and think papers have a long life ahead of them – at least 10 years.

I suppose this is called hedging your bets and with the latest figures issued by Trinity Mirror indicating that overall print revenue has fallen by 10.3%, the focus is also on tight management. The Guardian reports that the company plans to make savings of £15m this year, largely as a result of newsroom costcutting. Periodic industrial action by journalists across most of the the group’s titles is the new normal.

As is the willingness of certain journalists to speak out against what they see as the traditional local journalism model under mortal threat. Last week, award-winning former Croydon Advertiser reporter, Gareth Davies, posted a series of tweets to articulate his frustrations. The Trinity Mirror-owned Croydon Advertiser, he tweeted, had been reduced to a thrown-together collection of click bait written for the web where reporters had been misled and taken advantage of. Now, he wrote, the paper’s only role was to prop up the website with (increasingly) meagre advertising revenue.

Davies has expressed similar disquiet before – but two years on, his views have even greater urgency. Writing on the consistently excellent SubScribe blog, he clearly outlined a situation where, in his view, he was witnessing the beginning of the end of the Advertiser as a newspaper in the business of news.

He wrote of a journalist of 45 years standing being replaced by “two part-time reporters tasked with writing lists for the website” and an industry so ravaged by cuts and forced changes that it was unable to fully provide a public service and be a vital part of democratic accountability. Such was the situation, said Davies, six trainee reporters now cover an area with a population of 3.5m.

Many of Davies’ claims were quickly rebuffed by Trinity Mirror – a spokesperson claimed in response that every one of his points was either a misinterpretation of basic standard practice or completely untrue. But the landscape which Davies wrote about is instantly recognisable to local journalists everywhere and it prompted Dominic Ponsford, the editor of the Press Gazette, to call for more intelligence from the frontline of local journalism, asking “Are there another 1,000 Gareth Davieses out there?”

To which the only answer is: probably, yes. Local journalism has seen a gradual decline in numbers for decades and in 2015 my colleague Andy Williams recorded that there were just 114 editorial and production staff working for Trinity’s Media Wales, compared with more than 700 as recently as 1999.

So while this may be a familiar story, according to Ponsford, local newspaper journalism is facing a dreadful crisis – at least half the jobs in local newspapers have disappeared in the past decade and sales and revenues continue to decline. It’s important to remember that the cost cutting and practices of Trinity Mirror do not exist in isolation – the other major regional groups, Johnston Press and Newsquest, operate in a similar vein.

So what’s to be done? On a civic level, the rise and success of community journalism and hyper local media has meant that, as Damian Radcliffe has illustrated, in a number of instances local authorities and those in power have been held to account. Where traditional local media has faltered, often “citizen journalism” has emerged to fill the gap. Issues of sustainability aside, this is undoubtedly a good thing.

But the inescapable fact is, to quote Jeffrey Dvorkin, journalism is being “Uber-ized” – and not just at a local level. Dvorkin argues that content isn’t created by salaried journalists anymore. Instead, it comes from freelancers, “citizen journalists”, bloggers and vloggers – and the use of their product occurs at the expense of older, more experienced journalists.

In this environment, existing journalists may become little more than collators of content, chained to their desks compiling listicles to satisfy their bosses who demand stories that generate more than 1,000 clicks and attract advertisers. This is considered the cheapest way to generate revenue. Remember that private news agencies are primarily engaged in the business of making money – not with fulfilling a civic duty. The effect of the digital economy is ravaging the traditional industrial landscapes and journalism is no different.

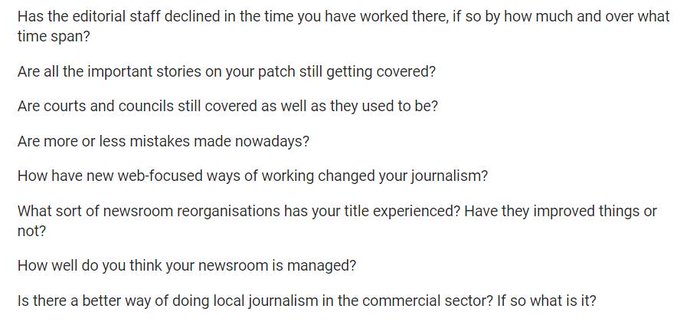

But all is not lost. The “Are there another 1,000 Gareth Davieses out there?” question posed by the Press Gazette is not a flippant one. They are inviting publishable responses from newsroom workers to a number of questions about staffing, workload and new practices. Early feedback indicates an overwhelmingly demoralised and overworked group of people – but the tone of the exercise is constructive, overall: the final question is: Is there a better way of doing local journalism in the commercial sector? If so, what is it?

It is impossible to overstate the importance of local journalism and the people who provide it. Local papers should keep the community informed about key issues while their big stories have always found an audience when followed up by the national press. As the Welsh Executive Council of the NUJ suggested a couple of years ago, regional and local journalism should be seen as community and national assets – their fate is too important to be left to the whims of media conglomerates.

In 2011, the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) suggested a number of proposals which, with some modification, could be workable. Amongst these are tax breaks for local media who meet clearly defined public purposes and direct government support for genuinely local media organisations.

The challenge is for all those involved – Trinity Mirror, its fellow regional publishers, journalists and government – to find a way to keep local reporting alive. We’ll all be worse off if they can’t.