Objectivity and impartiality in digital news coverage

Posted by: Professor Richard Sambrook

Cardiff’s Director of the Centre for Journalism, Professor Richard Sambrook, asks whether traditional journalistic disciplines are relevant in a digital environment, in an essay from the Digital News Report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Are the traditional journalistic disciplines of objectivity and impartiality relevant or wanted in a digital news environment? Many practitioners and commentators argue that they are not – that editorial approaches suited to the middle of the last century, with a scarcity of bandwidth and in an age of media concentration, are now redundant in the digital age of plenty.

Broadcasters in many countries have been regulated to deliver impartial news. Print journalism has never been regulated in the same way, but the professional codes, standards, and norms of journalism, which developed in the early 20th century, delivered similar standards in the news pages for many decades. However, in the 21st century, much has changed.

As the American software entrepreneur, Marc Andreessen, recently argued:

The practice of gathering all sides of an issue, and keeping an editorial voice out of it is still relevant for some, but the broad journalism opportunity includes many variations of subjectivity. … the objective approach is only one way to tell stories and get at truth. Many stories don’t have ‘two sides.’ Indeed, presenting an event or an issue with a point of view can have even more impact, and reach an audience otherwise left out of the conversation.

Andreessen is reflecting the popular growth in online opinion, advocacy, or activist news and ‘news with attitude’ in services like, Vice, Buzzfeed and numerous YouTube channels.

But advocacy, of course, is very different from objective newsgathering. What might have been left out to strengthen a case? What evidence is there to support a subjective view? Can we believe everything we read?

A biased source is just that, and cannot be relied upon to be accurate.

Male respondent 45-54

Verbatim comments from UK only

Who and what we trust in the digital world, awash with information and opinion, is an important issue. It’s not a new problem. The English poet John Milton, arguing against the licensing of pamphlets in the 17th century, believed market forces would drive out falsehoods: “Who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?” he wrote (in Areopagitica).

However, some believe in today’s environment the truth can be outnumbered in an unfair fight. Wall Street Journal columnist, Peggy Noonan, commenting on conspiracy theorists after President Obama announced the death of Osama bin Laden, wrote: “Here is the fact of the age: People believe nothing. They think everything is spin and lies. The minute a government says A is true, half the people on Earth know A is a lie. And when people believe nothing, as we know, they will believe anything” (Wall Street Journal, 11 May 2011).

As journalism reinvents itself in the digital age, the issue of trust – and brand – is crucial. Can a new trusted brand be built from the ground up (as Pierre Omidyar and Glenn Greenwald are trying to do with First Look Media)? Can old trusted brands like Reuters or the New York Times successfully reinvent themselves for a new generation and stay true to the values that they were built upon 100 years ago?

Or, as Clay Shirky, Emily Bell, and CW Anderson argued in their Tow Center paper, “Post Industrial Journalism”, is the individual journalist rising above the organisation as the key driver of trust, engagement, and consumer loyalty?

This year’s research offers some important insight into these questions.

First, the consumer appears to be more keen on traditional approaches to trusted journalism than many commentators.

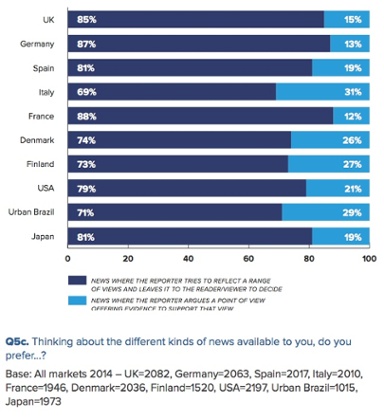

Among those surveyed there was strong support for the idea that a reporter should present a range of views and allow the consumer to decide what to think about them. This suggests that diversity of opinion, a key element in the old approach to impartial news, is still valued.

I want the full range of facts to work with, not just the select few that someone else decides I should know.

Male respondent 25-34

There are some cultural differences: the UK and Germany seem particularly keen on this approach, Italy and urban Brazil the least keen with close to a third preferring a reporter to argue a particular point of view.

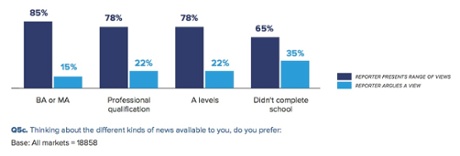

It is clear also that education and economic prosperity play a role as well – with this survey confirming previous studies which show that those with higher education, and higher incomes, prefer to make up their own minds about issues rather than have a single point of view given to them.

Ofcom research in the UK has shown nearly double the interest in news from those categorised as in the higher AB demographic group than C2s or DEs. Pew research in the US shows nearly twice the level of knowledge about news and current events among college graduates compared to other groups (Ofcom, New News, Future News (2007); Pew, What Americans Know 2007).

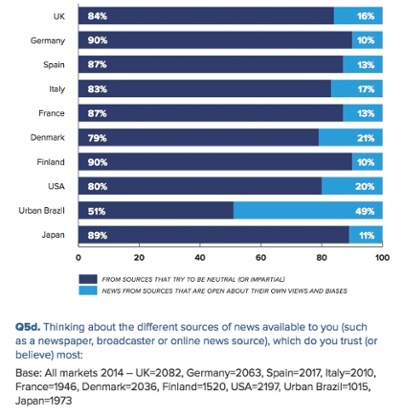

The same holds true for brands, with most countries preferring sources of news that try to be neutral over those with clear bias.

Again urban Brazil is an exception with an even split – and they also have a clear view that brand is important to trusting the news. So even if they are not keen on the traditional editorial drivers of trust – objectivity and impartiality – their choice of brand determines what they trust.

I object strongly to newspaper proprietors trying to manipulate public opinion for their own political ends by requiring their staff to adopt given lines.

Male respondent 55+

The figures also support those who argue for the rise in importance of the individual journalist over the brand. In the US more than half those surveyed said it was the individual reporter they trusted. In an age of social media and declining deference, it seems individuals may offer more credibility than institutions.

There may be a number of factors at work here. First, homophily – or the echo-chamber effect. Do consumers simply prefer, and therefore trust, news brands which accord with their personal views? In the US, Fox News has regularly come top of the most trusted cable news networks – while this year simultaneously, in the same survey, being the least trusted (with about a third of those surveyed opting for one polarised position or the other). Fox News, of course, has a clear right-wing agenda which viewers seem to either love and trust – or hate and distrust.

But if viewers trust those brands which simply accord with their own views and prejudices, are they necessarily well informed? Perhaps not. Again surveys in the US suggest Fox News viewers to be the least well-informed among cable viewers.

This indicates that there might be real risks to public understanding from the growth of subjective or advocacy news without an underpinning of more objective information.

Secondly, if there is a significant level of distrust (eg 50%) of some types of news sources it may be a straightforward barometer of opinion – or it may be that public expectations of quality and trust run ahead of performance and those news sources are effectively being ‘marked down’ due to public disappointment in them. We have been through a period in the UK where the media’s performance and standards have undergone intense criticism – with the Leveson inquiry into the UK’s tabloid press and successive editorial crises in the BBC, the UK’s dominant public broadcaster.

I would trust a source that tries to be neutral or impartial because I believe you get a better more balanced view

Female respondent 45-54

Finally, the solid support for objective news may reflect a public who do not yet recognise the arguments about the changing media ecology and offer answers simply reflecting what they have traditionally believed news organisations should represent. Plus there could be an attitude–behaviour gap between what people say they want from a news service, and what they choose to consume.

Questions of who you trust, and why, are complex. Greater qualitative research into the attitudes underlying these figures is needed to fully understand the dynamics of trust in a digital news environment, but cultural, educational, and economic factors clearly influence consumer choices.

If you are British or German you will have a stated preference for more traditional approaches to news. If you are Italian or Brazilian, you may prefer subjective news.

If you have a university degree and a good income you will prefer to have evidence set out for you to make up your own mind. If you are less well-educated or less well-off you may prefer a journalist to interpret the news for you.

If you know what angle they’re taking, you can interpret/understand their news accordingly. If they’re trying to please everyone, they’re appealing to no one. Being middle of the road is never inspiring.

Male respondent 35-44

Some commentators suggest that “transparency is the new objectivity”. In other words, if a news organisation or a journalist is open about their biases or personal views then the consumer can take them into account and trust the source as a consequence. This research suggests there is still an appetite for diversity of views and for evidence on which to base opinion – in other words, transparency alone is not enough.

Although the news landscape is changing rapidly with exponential growth in the sources, styles, and types of news available, audiences appear more attached to the traditional norms of balanced and impartial news than some might suppose. The question going forward is how well that sits among the growing range of digital services seeking to establish themselves by adopting a point of view to maximise impact.

This post originally appeared in the Guardian (12/06/2014)