Private messaging apps could push eyewitness media under the radar

Posted by Damian Radcliffe

As newsrooms get to grips with finding and verifying stories shared publicly on social networks, a new set of challenges are beginning to emerge as users prioritise privacy and simplicity.

Two new social phenomena got the technorati buzzing last year.

The first was the rise of anonymous social networks manifest in channels (with wonderful URLs) like Secret and Whisper; and the seemingly ubiquitous Snapchat. Such has been Snapchat’s ascendancy that it’s now being spoken of as a $15bn dollar company, up from $10bn in August.

The second, was the emergence of FireChat, which achieved global notoriety after being used by organisers of the umbrella protests in Hong Kong. What was particularly noteworthy about this case is that protestors purloined usage of their network for their own purposes.

These developments throw up a whole host of issues which lie at the heart of the work being done by Eyewitness Media Hub and others (including me). In particular, they highlight how new networks are being used by communities in different and at times unexpected ways. This in turn presents both challenges and opportunities around issues such as content discovery, verification and publication.

I saw first-hand over the past couple of years how these traits manifested themselves across the Middle East, where channels like Instagram, BBM and WhatsApp are increasingly being used by social media users as far more than simple SMS replacement services. Alongside more expected outcomes such as connecting with family and friends, these services are also harnessed for everything from e-commerce activity, to debate and discussion on a wide range of topics.

The reasons behind this growth requires more research and exploration, but arguably it’s part of a global trend which is seeing private messaging networks like WhatsApp, Snapchat and Line, continuing to grow rapidly. Research by the agency We Are Social reveals the global popularity of these services.

And although these are primarily designed as messaging apps, you can easily make the case to say that they have become so much more than that. Users are meeting new people, posting pictures and status updates, debating issues du jour and engaging with brands; many of whom are experimenting at how to best get into these new social feeds.

So what’s driving this growth of messaging apps?

In part, I believe that the simplicity of these services and their interfaces is a factor. Usability matters, especially for busy social media users with accounts across a variety of networks. And whilst churn is a factor for some demographics, many social networkers are simply adding more services to the suite of social channels that they use. In a time-pressed digital environment, ease of use becomes increasingly important.

The other major consideration in this arena is privacy. There is a perception that messaging apps are more private, and that this can encourage the types of conversation and behaviours that would not necessarily be engaged in on more open networks.

In the Middle East, this is already happening, with private groups being used to share and debate rumours and items in the news. New research published at the end of last year by Qatar’s Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ictQATAR) revealed that WhatsApp was the primary source of news for Qatari internet users.

The importance of having a forum to discuss the veracity of what’s being discussed online is also reflected in ictQATAR’s study (disclaimer: I led this project, before relocating to the UK at the end of 2014), given that 85% of internet users — from a sample of 1,000 — felt that social media is “helping to spread rumors and false information.” This was the most negative aspect of social media identified by the study, with minimal variance towards this issue across different demographics.

However, these services need to be used responsibility, as manifest in last summer’s report that an Israel family discovered about the death of their son via a WhatsApp message sent to a large group of people across the country.

But given stories like the recent case of a US expat recently being imprisoned in UAE for a “Facebook rant” about his Abu-Dhabi based employer — a tirade which he posted whilst on leave in the US — is it any wonder that many social media users increasingly prefer the relative privacy of closed groups on messaging apps; groups where your identity can be kept private and the usage of fake names and identities is prevalent.

For journalists and media organisations, this emerging trend presents a number of new and on-going challenges.

The first is the realisation that a substantial amount of eyewitness media is offline, and may become increasingly so. This includes images, video, status updates and discussion related to that content. As outsiders looking in, how do we access and engage with these communities?

Alongside this, how do we trust the accuracy of these channels? Verification in the social age is a constant challenge for news organisations, and the plethora of services being used by social networkers simply adds to this complexity. This is especially the case with channels, like messaging apps, where real world identities can easily — and often purposely — be by-passed.

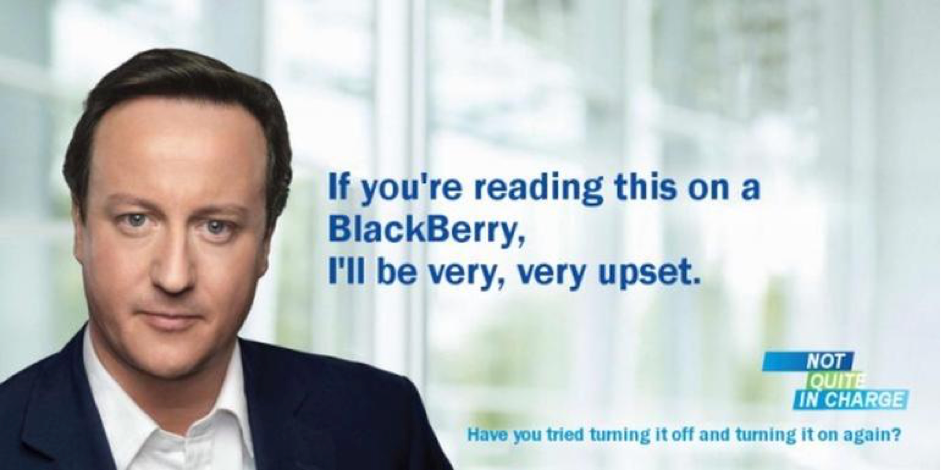

Finally, there’s also the challenge for policy makers about how to manage this phenomenon. David Cameron’s knee-jerk response to the UK riots of 2011 to close down BBM, or to ask social networks to share information with the authorities, was proved to be unviable.

Meanwhile, as advocacy groups like Global Voices have shown, Government authorities around the planet are frequently threatening to ban services like Viber, WhatsApp and Line as a result of their potential as a tool for politically charged discourse (nevermind their potential impact on the revenues of state sponsored telcos).

One thing’s for sure, messaging apps are here to stay. Until the next big thing comes along at least. As a result, how we can best harness these channels to tell important stories -whilst at the same time ensuring journalistic standards of accuracy, consent and safety, are upheld — is a discussion we need to have. And keep having.

This post was originally published on Medium for Eyewitness Media Hub.