Propaganda and the Press in World War I

Posted by Dr John Jewell

Over the weekend the Government announced that as part of the World War I Centenary events beginning next year, paving stones will be laid in the home towns of every UK soldier awarded the Victoria Cross. The BBC reported that, ‘a total of 28 will be unveiled next year to commemorate medals awarded in 1914 and others will be laid in every year up to 2018. Plans to restore war memorials around the country have also been announced. Help will be given to local communities and a website will be launched so people around the UK can obtain funding and support to ensure all memorials are in good condition by November 2018.’

This is an admirable venture lest no one forgets the horror and scale of death suffered in this most brutal of conflicts. In four years Britain endured 658, 700 fatalities, 2, 032, 150 wounded and 359,150 men missing in action. This adds up to total number of 3,050,000 casualties.

Astonishing isn’t it? And this is before one considers the impact on the home front. The mother’s without sons, the women without husbands and so on. Every village in every British city has a war memorial where we can read the names of the dead and only imagine the impact such tragedy had, and in many cases, still has, upon communities.

When the centenary events begin I hope we begin to examine why it was that so many, many men enlisted to fight so willingly. What was it that made young males the country over march together on their town halls, united in the common purpose of defeating the Hun and defending Britain? I would argue that enlistment and commitment to the war cause was the result of sustained propaganda carried out by the government – aided at every turn by a compliant and enthusiastic British press. During WW1 noted war historian Phillip Knightley has stated, ‘more deliberate lies were told than in any other period of history, and the whole apparatus of the state went into action to suppress the truth.’

When war broke out in 1914, it did so to flag waving and patriotism. Men were promised honour, glory and a conflict over by Christmas. These were times of great social inequality, remember, and these disenfranchised boys from the poorest, most hopeless communities could for the first time be useful. The army offered food, clothing, camaraderie and the respect of the nation. The lure of these things should not be underestimated. Their king and country depended upon them. So join up they did. It became a tribal, collective endeavour – many battalions were made up of men from the same villages, who went to the same schools and clubs. They joined together and a great many died together.

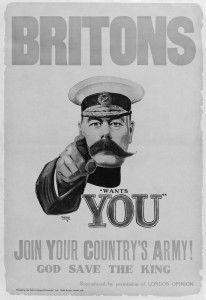

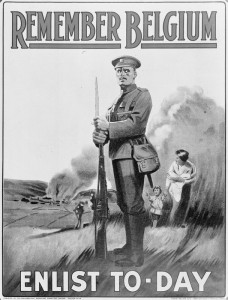

The propaganda posters told these often pathetic young men that they could be part of something special, to serve their country in righteousness. Many posters appealed to individuals personally, they preyed on the insecurities men might feel if they did not join up. Their masculinity was questioned, their fitness to be a father, to be a citizen and above all, to be a man. Not to join was cowardice – a treacherous act which would bring shame upon their family and nation.

The German soldier himself was capable of rape, mutilation and torture. Stories of Hun atrocities in Belgium were front page news despite there being little proof of their occurrence. The Times of 8th of January , 1915 stated: ‘the stories of rape are so horrible in detail that their publication would seem almost impossible were it not for the necessity of showing to the fullest extent the nature of the wild beasts fighting under the German Flag.’

What the government and press were doing was communicating the absolute necessity of conflict. Germany and its leaders were demonised. She was the antithesis of Britain and her values. And as Aldous Huxley wrote in the ‘Olive Tree’ (1937): ‘The propagandists purpose is to make one set of people forget that other sets of people are human.’ Under these circumstances, who in their right mind could stand idly by whilst this evil regime wreaked havoc throughout Europe?

That the press wilfully aided the war effort to the extent that truths were hidden from the public is all too evident. By 1918 Lord Beaverbrook, later the owner of Express newspapers, was Minister of Information. Lord Northcliffe, owner of the Times and Daily Mail was in charge of all propaganda directed at enemy countries. Robert Donald, editor of the Daily Chronicle, was director of propaganda in neutral countries.

Those journalists who actually reported on the conduct of the war (and there were only five) were bound by the strictest of restrictions. Reporters on the front line could not say where they were, refer to regiments or mention any soldiers other than the commander in chief. But they were treated as members of the army – given uniforms, a rank and they were housed well. The point is they were there for propaganda purposes: to provide stories of heroism, aid recruitment and also to protect the high command from criticism.

Indeed, some of the copy that came back from the front seems ludicrous and offensive to us now. Herbert Russell sent a telegram to Reuters news agency on July 1st 1916 about the battle of the Somme on its most calamitous first day: Good progress into enemy territory. British troops were said to have fought most gallantly and we have taken many prisoners. So the day is going well for Great Britain and France.’

After the war, another of the five correspondents, William Beach Thomas wrote in his memoirs of his shame:

‘A great part of the information supplied to us by (British Army Intelligence) was utterly wrong and misleading. The dispatches were largely untrue so far as they deal with concrete results. For myself, on the next day and yet more on the day after that, I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written, for the very good reason that it was untrue. Almost all the official information was wrong. The vulgarity of enormous headlines and the enormity of one’s own name did not lessen the shame.’

World War I was a time of great social change – not in least in the way that people read newspapers. David Jessel, in his wonderful documentary on war reporting, highlighted the fact that this was the first time that ordinary people began to realise that newspapers did not necessarily tell them the truth. What was being written in dispatches or analysis about the glorious progress toward victory was not the experience of those on either the war or home front. Lieutenant Ulrich Burke of the 2nd Battalion Devonshire Regiment wrote in 1916, ‘When we did read the newspapers it made us angry…[Y]oud read in the newspapers, ‘No action on the Western Front’. It didn’t seem to warrant, when you’d lost fifty men killed and an equal number wounded, a mention. …..It used to annoy everybody terribly. Very little action on the Western Front.’

So when we read next year about the heroism of all those dead men, when we pause to consider their bravery and sacrifice we should remember also the course of events which did not let the British public know about the conduct of the war. A system of propaganda which romanticised and demonised, mislead and obfuscated. As Lloyd George, Prime Minister in 1916, told C.P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian as was: “If the people really knew [the truth] the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don’t know and can’t know.”