The Daze of Future Past? The Wolverine, Franchises and Fandom

Posted by Dr Ross Garner

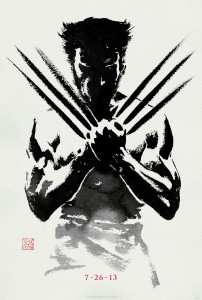

Recently, after a few delays, I finally got around to seeing The Wolverine (Mangold, 2013). Amid all of the hype that surrounds the now-institutionalised summer blockbuster season, this was the film that I’d been looking forward to for a long time. As a film scholar and enthusiast, my interests have always circulated around the more devalued end of the spectrum. Forget Fellini, Bergman or Loach, it’s the genres with dubious reputations (e.g. science fiction, fantasy and horror) and the overly-commercialised franchise blockbusters that interest me. Moreover, as an avid fan of (most) of the previous X-Men movies (just don’t mention X-Men: The Last Stand (Ratner, 2006) and what happens to Rogue (Anna Paquin) and Magneto (Ian McKellen)), as well as other iterations of the X-Universe in comics, computer games and television cartoons, The Wolverine had extra appeal. For the most part, The Wolverine didn’t disappoint.

Recently, after a few delays, I finally got around to seeing The Wolverine (Mangold, 2013). Amid all of the hype that surrounds the now-institutionalised summer blockbuster season, this was the film that I’d been looking forward to for a long time. As a film scholar and enthusiast, my interests have always circulated around the more devalued end of the spectrum. Forget Fellini, Bergman or Loach, it’s the genres with dubious reputations (e.g. science fiction, fantasy and horror) and the overly-commercialised franchise blockbusters that interest me. Moreover, as an avid fan of (most) of the previous X-Men movies (just don’t mention X-Men: The Last Stand (Ratner, 2006) and what happens to Rogue (Anna Paquin) and Magneto (Ian McKellen)), as well as other iterations of the X-Universe in comics, computer games and television cartoons, The Wolverine had extra appeal. For the most part, The Wolverine didn’t disappoint.

Despite pre-publicity interviews and press coverage promising a ‘darker and deeper’ tone, these claims were perhaps overemphasized. Yes, this is a character-driven movie that places Hugh Jackman’s Logan/Wolverine at its core and explores his tortured psychology. Yes, the film goes a little further with the brutality of its fight sequences and use of language than, say, last year’s The Amazing Spider-Man (Webb, 2012). At the same time, the movie’s setting in Japan adds a different visual flourish to the mise-en-scene (something another JOMEC colleague would be better placed to comment on than myself). However, to me these press discourses arguably speak more of branding practices and the need to accrue distinction to a film within another crowded summer season for big budget superhero/sci-fi movies.

After all, The Wolverine’s key pleasures remain its impressive action sequences and special effects (see the fight atop a high-speed bullet train and the eventual reveal of the Silver Samurai) as well as its combination of heroic narrative and performance as Jackman explores Logan’s brooding intensity and acceptance of his true nature to fight the good fight with aplomb. OK, we’re still in the ideologically-conservative realm of the white male American outsider hero here, but this reading shouldn’t cloud other pleasures that a film offers such as performance, choreography, technical achievements or aesthetics.

However, despite immensely enjoying The Wolverine’s 126 minute duration, the movie’s jump-out-of-your-seat-and-punch-the-air moment was, for me, reserved for the post-credit scene. The sequence’s seemingly humorous set-up, where Logan (who, for those not fluent in X-Men, has the metallic substance adamantium fused to his skeleton and results in his iconic claw-like retractable blades) has to pass through an airport security scanner, gradually reveals its bounties. First, we’re treated to a glimpse of the logo for X-Universe uber-villain Bolivar Trask’s Trask Industries and his mutant-unfriendly robot Sentinels. Then, as coins start to mysteriously float through the air, time stops and McKellen’s (presumed sterilised if you believe the aforementioned X-Men: The Last Stand) Magneto reappears. It gets better, though. Finally, we hear the soothing tones of Patrick Stewart’s voice and X-Men leader Professor Charles Xavier (with his iconic wheelchair) makes his entrance (Professor X was also killed during The Last Stand. I told you it was problematic). Cue a moment of decidedly non-academic whooping in the cinema from yours truly. However, after the fanboy moment had passed, the pleasure I derived from this sequence (which was included to set-up next year’s X-Men: Days of Future Past (Singer, 2014) film) made me think about critiques of Hollywood’s increasingly franchise-driven nature and the pleasures that this provides to fans and audiences.

A crude response would be to use my reaction to The Wolverine’s post-credit sequence as an entry point for repeating established aesthetic judgements about the ‘quality’ of Hollywood’s blockbuster output. After all, if the most enjoyable thing about a movie is what is technically an advert for another Hollywood blockbuster, the actual film can’t be up to much, can it? Such a reading overlooks both the industrial role that these promotional items fulfil and the affective dimensions these potentially provide (fan) audiences with. Extra scenes are but one example of the increasing range of paratextual elements produced by the media industries to sustain the visibility of, and build hype for, forthcoming films, TV series, albums and so on.

As Jonathan Gray explores in his book Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and other Media Paratexts, our contemporary media landscape is now awash with a range of promotional paratexts that includes websites, action figures, computer games, DVD extras and so on. Part of the role of these paratexts is to help frame audience expectations for either future installments of ongoing franchises, alternate iterations of established characters (e.g. franchise reboots or versions of a text intended for different target audiences such as more child-focused cartoons) or new TV programmes and, despite their rarity due to the industry’s predilection for ‘pre-sold’ elements such as comic books, Hollywood blockbusters (e.g. Inception (Nolan, 2010) or Looper (Johnson, 2012)).

This is undoubtedly the intended function of The Wolverine’s post-credits sequence. My reaction to this paratext is framed from a fan perspective as excitement is generated from both the first glimpse of how important characters from the X-Universe (Trask’s company and the Sentinels) will look on the big screen and the reappearance of favoured characters/actors that indicate the franchise’s continuing nature (and hopefully a return to its former glories). For non-fans, however, the scene works to raise awareness of the forthcoming Days of Future Past movie as well as generically framing expectations (what type of sf/fantasy plot devices have occurred for previously-deceased characters to have returned?) and providing familiarity to audiences via iconic stars such as McKellen and Stewart. Audiences can then, should they be so inclined, further their interest in the forthcoming movie via the internet as, not only can detailed production information be found via established sites such as the Internet Movie Database or Twitter, but professionally-designed websites such as that for Trask Industries can be explored to either fill in knowledge gaps or obtain sneak glimpses of key characters.

On the one hand, yes, promotional paratexts such as The Wolverine’s post-credit sequence and the Trask Industries website constitute an extension of the ‘high concept’ marketing strategies that Justin Wyatt explored in relation to blockbuster cinema as they establish recognisable logos and aesthetics that can be exported to other merchandise for future commercial exploitation. However, as scholars of media fans have pointed out, reducing our understanding of these practices to the commercial bottom line overlooks how audiences affectively engage with favoured media franchises.

Fans moving across websites for fictional brands, or wearing t-shirts/bags emblazoned with their logos, are not simply being co-opted into commercialised and commodified spaces (electronic or otherwise) and identities. Fans can instead use paratexts as opportunities for entering and maintaining the consistency of the ongoing narrative world – what Matt Hills calls the hyperdiegesis – of their favoured franchise and employ these to extend the affective pleasures that they obtain from their fan objects via blurring the lines between fiction and ‘reality’ and allowing the former to seep in to the latter. Rather than using my reaction towards The Wolverine as a way of bashing Hollywood’s output, or demonstrating how fans are duped into the commercialised spaces of media industries, we instead need to address how the franchise-driven nature of Hollywood opens up possibilities for the continuation and maintenance of identities and affect.

I’ll see you next summer. May 23rd. In a Trask Industries t-shirt.