The return of Spitting Image

Photograph: Avalon/Mark Harrison

At the end of last month, it was announced with some fanfare that the seminal 1980’s ITV puppet show satire, Spitting Image, was returning to our screens.

In its heyday the show was watched by 15 million people and it can be reasonably argued that the latex representations of politicians such as Norman Tebbit (as a skinhead bovver boy), Kenneth Baker (half human, half slug) and Michael Heseltine (a wide eyed and feral Tarzan) filtered down into popular consciousness rendering the fictional far more memorable than the actual.

Apparently, the first episode of a proposed new series has already been filmed and Roger Law, one of the show’s original creators, confirmed to the Guardian that the producers were in talks with US TV networks about bringing the programme to a global audience.

This is significant because the primary target of the newest incarnation of Spitting Image is going to be, unsurprisingly, the so called leader of the free world, Donald Trump. In a tempting taster for what’s to come, Law, who describes Trump as “an absolute monster” says the President will be seen (or rather his puppet will be seen) composing his much criticised tweets from his anus.

If this is too cartoonish for some, let’s hope the programme is more hard hitting. One of the main criticisms first time round was how comfortable it all became in the end. Former Deputy Leader, Roy Hattersley was happily pictured with his puppet – a particularly drooling, savage caricature. Whilst the afore mentioned Norman Tebbit wrote in 2008 that he rather liked his portrayal and, in his view, “it never did me any harm”.

But the new show is unlikely to feature much in the way of British caricature – In Law’s words: “If you’re going to go after the b***ards, you may as well go after the biggest b***ards there are, hence America.” Which is a shame, because if the first incarnation of the show was known for one thing overall, it was its portrayal of Margaret Thatcher, whose puppet was voiced by comedian Steve Nallon. And even though the ingenuity of the puppetry and the quality of the voice mimicry was often more noteworthy than the standard of the jokes, I sincerely hope Boris Johnson receives a similar level of attention. The opportunities for satirical treatment are surely there, despite the current PM’s unstoppable and inglorious descent into self-parody.

Therein lies the issue. In these confused and uncertain times, where the leader of the free world can be justifiably described as delusional, duplicitous, frequently terrifying and frankly ridiculous, does satire have a role to play?

Some commentators have been proclaiming satire as moribund for years. In 1973, US critic Tom Lehrer mourned its passing when the Nobel Peace prize was awarded to President Nixon’s Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger. These days there are those who contend that satire, that is to say the act of criticising those in power through the medium of humour, is dead (again) because the likes of Johnson and Trump, in their ridiculousness, are simply impossible to satirise.

Journalist Sean Moncrieff argues that for satire to be effective, conventional norms have to be subverted. But in Trump and Johnson we have politicians who “revel in their buffoonery” and have sabotaged their respective roles (and the conventions of their roles) to a level almost beyond recognition. Hence, satire’s traditional usefulness is negated.

This is not a view shared by one of the UK’s greatest satirists, Chris Morris. In an interview to promote his latest directed film, The Day Shall Come, Morris told CNN’s Christiane Amanpour that anyone who says satire is dead is “handing in their cards and essentially telling the world that their imagination had ceased to function. Trump is a “field day” said Morris and satirists should “keep calling them out on what they do”. This is surely correct. A Johnson or a Trump may be ridiculous, but satirists need to not only criticise who politicians are but also, crucially, what they do.

What is without doubt is that Morris is one the great figures of British satire with a truly impressive back catalogue of work. His 1994 BBC2 series, The Day Today created and performed with, amongst many others, Armando Iannucci and Steve Coogan , is note perfect. As a critique up of a typical news and current affairs programmes in the manner of the BBC’s Newsnight, it manages to satirise the whole production of news – concerned as much with form as it is with content.

Morris occupies centre stage as a supremely confident, eloquent and disdainful Paxman type figure. Using what academic James Leggot refers to as the “heightened speech pattern that echoed the cadences and odd emphasis of well-known news presenters” he dutifully introduces stories of varying levels of absurdity. All the while the conventions of this type of news programme – the portentous music, cutting edge graphical displays and evasive politicians – are replicated and amplified with such skill as to have the viewer question momentarily whether they are watching the real thing. Even after all these years, Newsnight still relies on the tropes The Day Today managed to skewer so successfully.

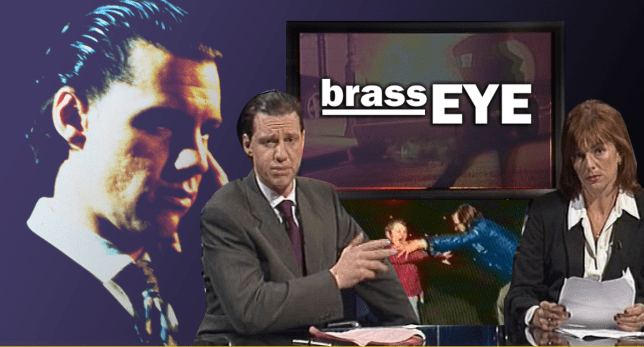

It was through Brass Eye though, that Morris cemented his reputation. Ostensibly another current affairs satire, this time for Channel 4, Morris satirised, amongst other things, the willingness of politicians and celebrities to utter palpable nonsense for the sake of public approval.

The most notorious episode, Paedogeddon, broadcast in 2001, was a critique of the media’s, in those days quite pronounced, fascination with paedophilia. The set up exactly resembles a current affairs programme and then an audience participation show. There are meaningless graphics, archive footage, outside broadcasts, staged interviews and underpinning the sense of absurdity are the celebrities and politicians spouting the most ridiculous platitudes in the name of public information. There’s Gary Lineker telling us of the charity “Nonce Sense” and Labour MP Syd Rapson telling us that that paedophiles were using “an area of internet the size of Ireland”. What Morris was satirising here was the willingness of public figures to say anything if presented to them in the right way and the willingness of the general public to believe anything that came out of their mouths. Not because they were experts in any particular field, but simply because they were in the public eye, on television and therefore important.

In this sense maybe Morris foresaw the rise of Trump. Here’s a man with no political track record spouting absurdities on a daily basis yet still lauded by his ever loyal base support who first saw his potential as the host of the American Apprentice. But, Morris in mind, we should be aware of what Trump does as much as what he says. Let’s hope the new Spitting Image will “keep calling them out on what they do”. As the editor of Private Eye, Ian Hislop, has written, there is cause for optimism in regard to the future of satire: “we should be resolutely positive and ignore the doomsters and gloomsters and naysayers, and look forward to, yes, the golden age that is coming up shortly”.