The toxicity of political communication

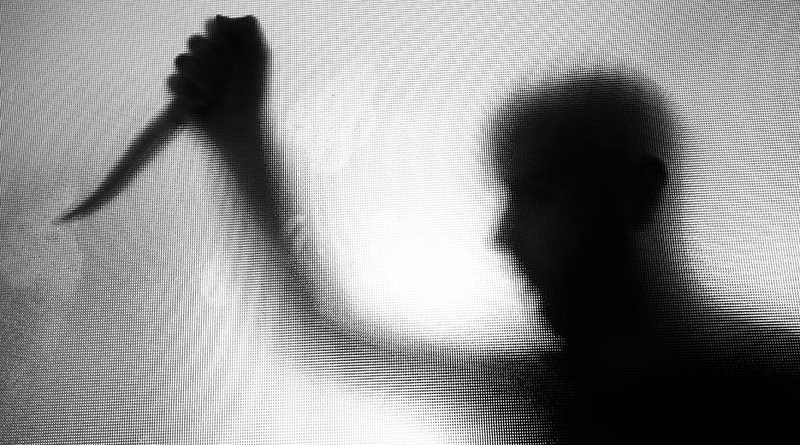

When the BBC’s former political editor Nick Robinson tweeted last week that people who you disagreed with weren’t “enemies or traitors” and that they don’t deserve to be “knifed or lynched or hanged” he was clearly passing comment on the toxicity of current political discourse.

The seemingly interminable wrangling over Brexit has polarised and divided opinion and the way in which these opinions are being expressed, has, in some quarters, seen proponents on both sides resort to the language of violence and intimidation.

The Sunday Times of October 21st illustrated this perfectly. It’s front page headline proclaimed, PM enters ‘killing zone’, whilst the adjoining report quoted an ally of former Brexit Secretary, David Davis, as saying: “assassination is in the air”.

Further on in the paper, a full two-page feature devoted to the deficiencies of Mrs May ended with a quote from an unnamed former minister: “The moment is coming when the knife gets heated, stuck in her front and twisted. She’ll be dead soon.”

And, while it would silly to suggest that the business of politics has ever been characterised by deference and good manners – one only has to consider the history of PM’s questions in the House of Commons for a reminder of how juvenile, base and degraded British democracy can be – the binary nature of the emotive Brexit debate has seen an increase in visceral and intimidatory language.

This talk of “knifing” and “assassinations” – though obviously meant in a metaphorical sense- is nonetheless crass and ill considered. We are only two years on from the appalling murder of Labour MP, Jo Cox, who was shot and stabbed to death outside her own constituency headquarters.

Thankfully, there has been some public condemnation. Robert Halfon, chairman of the Commons Education Committee told BBC Radio 4’s World At One that the use of such language was shameful and that MP’s shouldn’t go around “aping the kind of extremist trolls on Twitter.”

It’s a pity that these sentiments are apparently not shared by Stewart Jackson, the former Tory MP who was David Davis’s top adviser when he was Brexit secretary. On the day of the People’s Vote march a week ago, a man called Anthony Hobley posted on Twitter a picture of his hospitalised 12-year-old step son draped in a European flag bed cover.

The accompanying message said: My stepson had an operation yesterday @GreatOrmondSt. He’s incredibly brave but gutted he can’t be at the #PeoplesVoteMarch today with his brothers & sisters.

To which Mr Jackson replied – “what a pathetic cretin”.

It could be that we are, in the words of BBC media editor, Amol Rajan living through the utter collapse of manners and civility in our public domain – and social media appears to be to some extent significantly responsible.

And if we look across the pond to the leader of the free world we see a man whose success has been partially built on the daily utilisation of insulting and violent language. From his routine misogyny (often women are animalised – most recently his former aide Omarosa Manigault Newman, was a “lowlife” and a “dog” and Stormy Daniels has been called “horse face”) to the regular attacks on the media.

As a matter of fact, in August experts at the United Nations warned that Trump’s vitriolic rhetoric could result in violence against journalists. And, as I write, news comes through of A number of explosive devices sent to Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and CNN’s New York offices. As CNN has responded, now the debate has begun (again): what role does violent political rhetoric have on these real-life acts of violence?