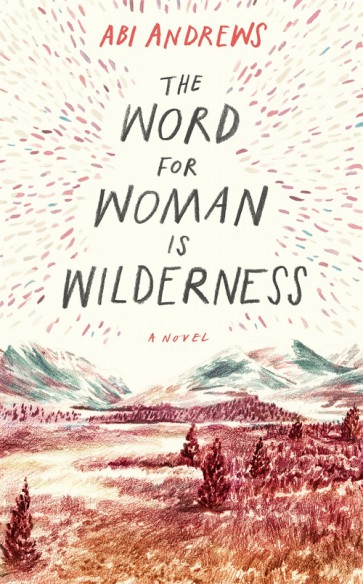

Abi Andrew’s first book, The Word for Woman is Wilderness, tells of the journey of Erin as she ventures North to Alaska. The trip is catalysed by the realisation that the wilderness narrative and the wilderness itself has been monopolised by men, and she is spurred on by a fiery determination to prove that women can do the same.

But as her horizon slips further away the closer to it she dares reach, Erin is forced to confront questions as vast and complex as the sublime spaces in which she contemplates them: what is the wilderness? Why have women been excluded? What is our position on earth, in the universe?

The humorous and ironic question which plagues her trip from the beginning, “am I doing it right?” reflects our saturated world and the way films and books can taint our experience of travel, not to mention our increased ability to watch others doing it via social media. “Am I doing it right?” reflects the hall of mirrors we’ve constructed for ourselves; always watching ourselves doing.

A double weight, since, according to Laura Mulvey women are never in solitude since we have internalised the male gaze and are therefore watching ourselves being watched, always. But that funny, quietly buzzing question which travels with Erin in all she does takes on a deeper resonance the further North she ventures, and in it, finally, is a question that relates to how we view our existence: the teenage “Am I doing it right?” becomes a rumbling: “Have we got it all wrong?”

Exclusively to Go With Me, Abi explores some of the themes of her work and probes even deeper into these questions:

Tell us a little bit about yourself, and how you started writing:

I’ve been a library goer since I was little and have always read a lot, although I have to say that until I reached maybe fifteen my canon revolved around books with talking animals in them. Then I started writing when I was a teenager. I knew I wanted to go to Uni, and my decision was as simple as liking books and writing; I chose a creative writing BA, and it was during my final year that I started the novel.

Was there a particular moment or event that inspired the writing of TWFWIW? How did it come about?

It was much like in the book. I watched Into The Wild the film about Chris McCandless, and it stabbed me in the heart. Then I wanted to go to Alaska, with my two friends I watched it with. But then we started to talk about how it’d be a different film if it was a girl at the centre of the story. So we decided to go to Alaska and make a documentary about what it would mean to do it as a woman. After a couple of hours the dream died; we were going into our third year of Uni, and we had no money. So I started to write it instead, to imagine how Erin would do the trip, and to make the documentary in my head.

It is by virtue of the subject matter full of essential contradictions which are difficult to detangle. For example, the way women at the same time have been cast out into the wilderness (and as wilderness) by men, but are still banished from it. Or how by leaving any imprint at all we are demolishing that which he had idealised as undifferentiated wilderness (that which is outside man, being made man by our presence and persistent symbol-making. Like the Anne Finch Poem A Nocturnal Reverie). How did this make the process of writing?

The idea of a journey and the making of a documentary about it was perfect as a premise to explore these things from. My mind kept changing as I went along and the book had many drafts. It became really important that I actually didn’t do the journey once I realised the problem of writing a wilderness, the documenting of a place that is supposed to be outside of human symbols. It started to strike me as such a tragedy that the wilderness McCandless went to is now a well trodden mecca, not so much because of him, but because of the film made about him.

But I sort of evolved into these ideas as the journey went along and as I was reading more into the themes. I almost went along in tandem with Erin, although of course writing fiction rather than nonfiction allowed me the dynamic of using my narrator to create layers of irony and doubt and things reterospectively, in order that it wasn’t too didactic, and to try to get the reader to participate and draw their own conclusions. It also allowed me to take a step back, with the imagined and fictional world of the novel as a playground for these ideas, holding wilderness as an idea rather than a true physical wilderness, which could be corrupted by writing it.

Did this make writing the book difficult? Especially given the questions is raises about the difficulty of saying anything with sincerity in today’s society but especially as women. Men can say things in solitude, but women are never not being looked at since we have internalised the male gaze and are thus watching ourselves being watched (according to Laura Mulvey, anyway). I noticed this in the way Erin will say something deeply moving about the shifting landscape, but qualify it by saying there should be cinematic music etc, thus distancing herself from it by referencing films she’s seen before.

I wanted to make this a thinking point in the book. Erin’s narration enacted how it might be very different for a woman, in order that we might start to think about why. Erin is often uncomfortable and doubtful about her authority as a voice and as a documentary maker, in the sense of being aware of her view-from-a-body. She knows the itch of being under the male gaze, as a woman. This makes her uneasy without awareness at first, and then once she realises it, makes her ashamed that she in turn reflected the gaze onto others, onto other less privileged women, and onto the natural world. Women are watching themselves being watched, and so Erin is watching herself watch others watch themselves being watched. Which is a rather disorienting volley of gazes.

Her uncertainty was important to me in terms of decolonising narratives of both the white and the western, the male, and the human, as centre of the universe. It was important as a resolution; that no man is an island, and although men have been saying things in solitude, they haven’t really, because they said them, in words, which tie them up in their humanity elsewhere from the island.

Have you made that journey to Alaska before, or is it all in the imagination? Have you yourself managed to find some wilderness as far as that’s possible?

I haven’t done the journey, which was important to the writing of it like I’ve said; that it was a fiction. To try to avoid as much of the ‘colonisation’ of the space entailed in writing it, by not actually writing it from personal experience. I tried to put myself there imaginatively, to use the particular concept of wilderness, with a character in it with a particular worldview, as a petri dish to see what would grow out of the combinations. I wanted it to be as convincing as a travelogue as possible, in order to engage with that genre and its problems with an objectifying gaze. I’ve never been far into any big ‘wilderness’, aside from some hiking trips, nothing on the scale of Erin’s journey. I’d still absolutely love to go to Alaska though.

Is it important for you that the book reaches a male readership as well as a female?

Yes! We accepted that in naming it ‘The Word for Woman…’ that it might be pigeon-holed as a book for women, and it mattered most to me that it reached women, putting it forward almost as its own secret club, like the masculine boy-scout ones we’ve always been kept out of. But really the title is a provocation, and I hope it does invite as many men to read it, as a challenge. Because at the heart of it it’s about 4th wave feminism, which wants to do away with gender reductionism for everyone, to the benefit of everyone, men included. I’ve had quite a bit of good feedback from men who’ve read it and didn’t seem to think that it wasn’t for them, and took a lot away from it still, which is fantastic.

What is your absolute favourite moment in Erin’s journey, and why?

When she’s coming down the mountain, because in a way I was coming off the mountain too. We both got to a place of no return; her realising that her documentary would ruin her wilderness, and me wondering how to even write if symbols corrupt and colonise and all of language is symbols. So talking her down off the mountain was also me talking myself down a little, and that part I really enjoyed writing.

It’s her homecoming, her coming back to herself. And I thought I found something to salvage from writing the wilderness, in that the symbols allow us to conceptualise how we feel about it, in order that we can feel, in order that we then want to enact care. The sharing of stories is a way to connect with others and the world, and a way to combat the nihilism of accelerationist environmental rhetorics, that tell us humans have corrupted and will go on corrupting the natural world, so we might as well let humanity implode and nature will rebuild from bacteria or something.

If readers could take away one thing from the novel, what would you have that be?

A thoughtfulness towards their place in the world, a body homecoming, a recognition that their body is theirs, and an awareness of how it is placed in relation to other bodies, human and nonhuman.

Who is your all time feminist icon / role model and why?

I mean I have many, and I tip my hat to a few brilliant female writers and thinkers in the book. But right now with having just bought the book into the world I have to say Rachel Carson first and foremost. First for writing Silent Spring, which was the book that woke me up to the way we relate to nature, dichotomising it as ‘other’ and apart from us, to be utilised for our needs or discarded. I think it’s significant that it was a woman looking closely at her home environment, and talking about responsibility towards preserving it, that kick-started the modern environmental movement, rather than someone on a colonial quest into a separate and pure wilderness.

She also wrote a trilogy of books about the sea, and has me thinking a lot about how to imagine subjectivities that are other to us, and how to word them, in order to get people to care about them. It’s amazing that she wrote these vivid and poetic books about the sea at a time when scuba diving had only just been invented and people really didn’t have much of an idea of what it was like down there. To me a true feminist has to be inclusive of not just other women, but other nonhuman allies too, and she did great work to expand our wonder and compassion to the worlds of ocean creatures.

What are you reading right now? What’s your favourite novel?

I don’t know about a favourite. I don’t think I’ve ever re-read a book before or could swear a single favourite. I love anything by Maggie Nelson. Recent things I’ve read that I really loved were Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk, and Catherine Poulain’s Woman at Sea, about a woman on-board a deep sea fishing boat, which has the first line ‘you should always be trying to get to Alaska, but getting there, what’s the point?’ which is basically my book in one brilliant line! We had quite different ideas come out of what was, I think, a similar premise, but it’s a great book.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers? Especially women trying to find a voice?

I would say, find a writers group near you or if you can’t then start one in your living room. Make it female-identified only, even! Create a nourishing place in which to share your writing and talk about it with others. The support and creative criticism you can get in these kinds of places is invaluable, and is the first step perhaps before you are confident enough in your writing to share it with the wider world.