People add new words to their day-to-day language all the time without even thinking about it, so why does the addition of new words to a language that has missed a decade of evolution receive antagonism, especially from the most unsuspecting of places?

The smell of freshly baked scones permeates the air at 9:15 in Greens Café on the Isle of Man as the students settle in around the table, carefully placing their language papers around coffee cups and baked goods.

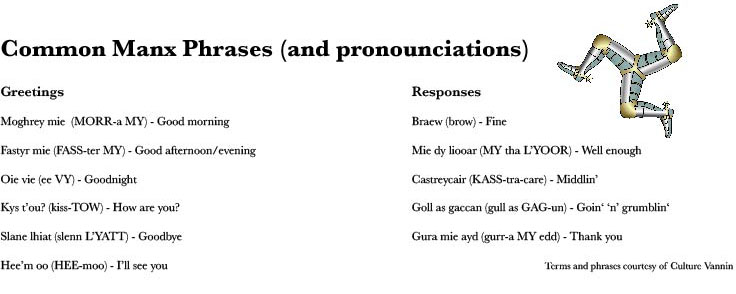

“Moghrey mie, kys t’ou?” asks Jamys O’Meara. (Good morning, how are you?)

Going around the table, each student responds and tells a bit about their weekend, sometimes pausing for a moment to try and grasp the elusive Manx word to describe mowing their lawn or clearing out the shed.

The rhythm of the language starts to fall into place, and the students begin to speak with more confidence until…

“Wait, how do you say WiFi?”

Edward (Ned) Maddrell, the last native speaker of Manx Gaelic, died in 1974, and with his passing, the language that was once spoken across the island dropped into obscurity.

In the last 40 years since Maddrell’s death, languages have continued their evolution with the addition of new technologies and the words to describe them, but Manx has remained in limbo, outdated, and, to some, no longer of use.

Phil Gawne, the current director of Mooinjer Veggey (an educational charity in the Isle of Man that promotes Manx learning for young people), recalls a certain incident when his children were young, and an elderly neighbour overheard Gawne speaking with his son in Manx.

“The great story I tend to trot out was when we were raising our children in Manx and [my son] was about four,” says Gawne. “And we brought the children up in Cregneash, which was great, a fantastic place. There were some other Manx-speaking kids at the time, and two or three older residents, one of whom used to drive around Cregneash of an evening, with the wife just have a peek to see what was going on and seeing them check that everything was still in order.

“Well, we bumped into him one day when we were heading out for a walk and we were talking away. And anyway, [my son] started running down the road. So I shouted something in Manx, you know, to come back. And then Norman, the fellow’s name was, sat in the car, held a pipe. The pipe jumped out of his mouth, ‘What are you doing speaking that language to that child?’ He was furious, absolutely furious. Couldn’t believe that we would do such a thing,” says Gawne. “Other than that, you know, everything else that, all the interaction I’d ever had with Norman was all a clear love of sort of the culture and ways of life and things of the past. But no, not the language!”

A ‘Living Language’

“Historically, people have perceived Manx as being something they’ve associated with the past,” says O’Meara. “Even if people are positively disposed to Manx, they may see it as something like a museum exhibition, or something that, for them, is of value but doesn’t have a part in the modern world.”

Many of the older generation of the Isle of Man hold similar views on the use of the language, though individuals like Gawne and O’Meara are working to change that perspective.

Like many of the other indigenous languages of the British Isles, Manx began to be seen as old-fashioned and a sign of poverty and backwardness in the mid to late 1990s, so when a resurgence of interest in the language and culture of the Isle of Man began, there was a couple-decade gap between when the language was last used and modern-day language needs.

O’Meara worked as the interim Yn Greinneyder, the Manx Language Development Officer, during the summer of 2019. He was responsible for the development of resources for the Manx language, teaching and promoting Manx both in and outside of schools, crafting translations from English to Manx and back again and more.

The Yn Greinneyder works with Culture Vannin, a part of a charity called the Manx Heritage Foundation, with the mission to support and promote Manx culture and language, as well as assist with translation and, when needed, word creation.

“Every language has to coin new words for items of technology, that’s very natural,” says O’Meara. “Whether or not a speaker actually uses them or not is another matter.”

On the Isle of Man, Culture Vannin and the Coonceil ny Gaelgey (Manx Gaelic counsel) have been some of the driving forces behind helping Manx become once again relevant to day-to-day use.

The Coonceil ny Gaelgey is the main translation service on the Isle of Man. Requests for translations come through O’Meara’s position as the Yn Greinneyder, and he sends them on to a translator on the Coonceil.

“If there are any words that didn’t exist in Manx, or any names, or any bits of jargon that didn’t exist, the translator would put forth a suggestion, and if everyone agreed, we would go forth with that,” says O’Meara, explaining the process of coining a new Manx word.

Translators, in creating a new word, will base it on already-existing Manx words, maybe creating a prefix or suffix to modify an existing word to help it fit, or using adjectives to describe in Manx the word.

“If anyone had any issues, they would put forth a suggestion, an alternative suggestion, and then a consensus would be reached upon the official term that would be used,” says O’Meara, but he stressed that no one is obligated to use that word, and if they prefer one of their own making, they can use that in place.

“I think we’re probably one of the few countries in the world that uses a different word than banana to describe a banana, when we talk about corran-bwee, a yellow crescent,” says Gawne. “ I think every other language in the world that I’m aware of says banana.”

The word that is agreed upon by the Coonceil does go down in the official Manx dictionary, and will be used in all official and governmental work, but not necessarily in day-to-day use.

It could be argued that because of the freedom allowed for Manx over the last five centuries since we really lost our links with Irish and Scottish Gaelic, the language has been more able to develop in ways that Irish and Scottish Gaelic haven’t.

Phil Gawne

Some language preservationists view any modifications to languages as altering the purity and authenticity of the language – thereby in some senses invalidating language preservation efforts like that of O’Meara and Culture Vannin.

“We just want to make sure there’s a constant presence of Manx,” says O’Meara. “Not just for Manx speakers, but to encourage other people as well to kind of, take control of the language.”

“Words in a language come and go, but it’s the fact people are using the language that is important,” says Gawne. “Even if they use English every now and then, as long as they are speaking Manx, that is what’s important.”

Overall, most people on the Isle of Man are supportive of Manx revitalisation efforts, but they have met with their fair amount of opposition. Trying to shift and change perceptions, especially those that have been passed down through generations, is a challenge for any organisation. One of the ways Culture Vannin is working to combat this perception is by providing language classes, like the one O’Meara runs at Green’s Café, for adults who wish to learn Manx.

“In the Isle of Man, similar to Ireland and Scotland and Wales to some extent, there has been a lot of antagonism towards the Manx language and the Manx culture for a lot of really complex reasons,” says O’Meara. He explained that a lot of this stems from a colonial mindset when the Isle of Man was first beginning to be settled by English settlers and has been ingrained in the minds of Manx people since.

“It’s kind of an internalised thing,” says O’Meara, “a lot of people, old Manx people, have these internalised views of antagonism towards the Manx language and Manx culture.” Individuals would be punished for speaking the language in pubs or in schools, and emphasis was placed on English as the language of sophistication and education.

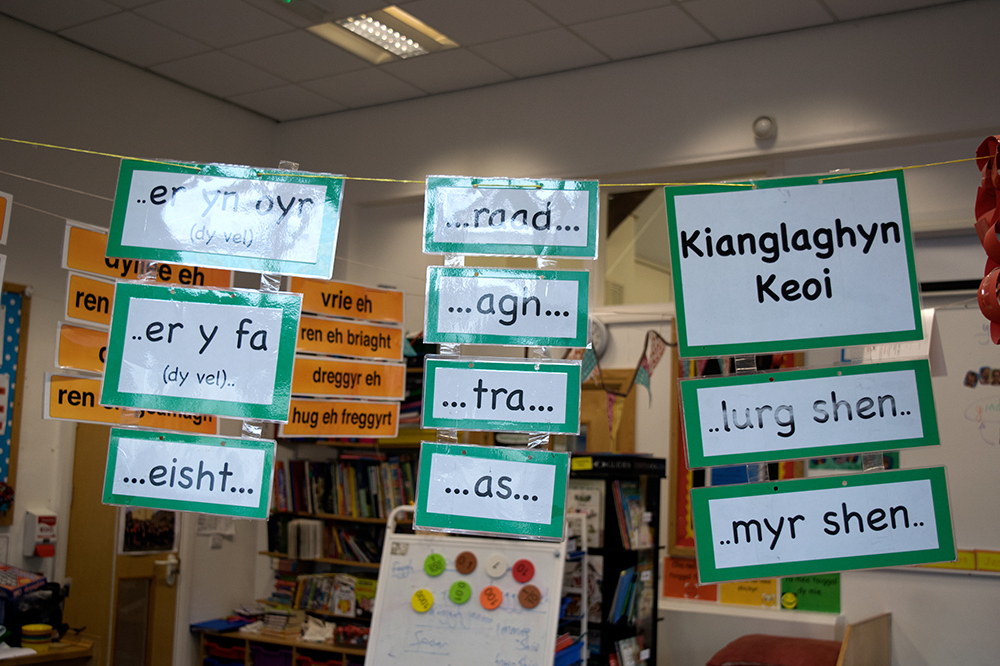

O’Meara, in his role as Yn Greinneyder, offers classes like those at Greens Café as a way to help re-introduce the language, and the newly added words, to adults. Gawne, with Mooinjer Veggey, founded Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, a Manx-medium primary school on the isle, as well as providing other nursery programs and language enrichment for younger people on the island.

There is also the challenge of explaining why learning and maintaining Manx language and culture is important to people who maybe feel as though the efforts and money put towards Manx may be better used elsewhere.

“A lot of things that seem intuitive to a language activist or someone who works with language is very unintuitive to people who don’t work in that field,” says O’Meara. “For example, we have Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, the immersion school, [and] if you work within the language, intuitively, you understand that as something that is beneficial to the children, to the culture. But to a lot of people, most people, that’s unintuitive for them.”

Manx Language Evolution

In the last decade or so, however, many of these perspectives have been addressed, and there has been a significant change in the way most people approach Manx.

“The government has started to recognise the importance of Manx as a part of cultural identity, as part of the branding of the Isle of Man, if you will,” says O’Meara.

The Manx language, while still very much a minority, is slowly gaining traction once again, and individuals like O’Meara and Gawne are working hard with their different organisations to continue the growth of the language. Already, their efforts are paying off. In 2009, Manx was classified as an extinct language by UNESCO, but in 2013 the language was reclassified as ‘critically endangered,’ the first language to be so according to The Guardian, and the Manx speakers are not done.

“[With

the] challenges we’ve faced, we’ve come a long way,” says O’Meara. As for the

future of Manx? According to O’Meara, it will come in the form of expanding

Manx outside of the classroom, back into homes.

As for the morning classes at Greens? While some might come for the free

scones, others are there to learn the language and make it the norm in their

homes.

When

people don’t know a word, O’Meara tries to enlighten them. WiFi, well, that’s

the same as in English. But if one wants to use Manx, eddyr-voggyl for

internet, culleeyn gyn-streng for wireless. Culleeyn gyn streng

eddyr-voggl (wireless internet).