Voter numbers in the 2019 Euro and general elections in Greece reached an all-time low. What is it that’s keeping voters in the home of democracy away from the ballot box?

The Greek sun is shining and the beach looks like a one-way street to anyone who lives close to the sea. On an island like Lemnos, at the North-East of Aegean sea, elections at a lovely Sunday at the end of May means that the island is going to be revitalized by the locals who live away from the island. Food restaurants’ and shops’ owners waiting for the electorate to turnout to ballot boxes and right after to deal with the heatwave by enjoying a cold beer at the tavern by the sea.

With elections taking place in a day like this, the possibility of people not to proceed to their polling place appears to become a fact.

The next day, the official polls indicate the noticeably high percentages of abstention which hit a new negative record in the history of Greek post war period and they corroborated the pre-elections polls about high abstention from the Euro and general elections. The mandatory character of the vote, according to the Greek constitution, is not enough anymore to bring the electorate to ballot boxes.

“I intentionally refrain from voting because I feel that my vote doesn’t have an impact anymore. It’s not us who decides, it’s the outside Greek powerful organizations who have pre-decided our future,” says Stamatis Limanis, the owner of a Greek restaurant in Myrina, the capital of Lemnos island.

Stamatis actively participated in all the forms of elections until September 2015, the general elections after July’s referendum in Greece. It was that time when he decided that not even going to the ballot box to give a blank or void vote would represent his disappointment towards the political system and the politicians. As Stamatis says, “The government asked for the people’s vote in order to reject it afterwards. That was a joke. Vote only counts when they want to elect people”.

“In 2015, people followed the guy who promised a paradise to them but they soon realized there is no paradise and we can’t go back to the heavenly past we have lived in,” says Theodoros Chatzipantelis, Dr. of Applied Statistics in Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The previous governments’ decisions and handlings, had one common result in people’s mind, that they were responsible for the financial crisis. The political scenery in Greece has been always caracterised by the predominance of two parties, the socialist one (PASOK) and the right-wing, New Democracy. As Stamatis says, “I’ve seen the two parties failing me and I was hoping that the forefront one, Syriza, would be better. It totally disappointed us”.

The 2015 referendum’s decision overturn and the following memorandum voted by a radical left government which was promising the abrogation of memorandums, created a sense of resignation. The election of a party that was standing with the public in protests and rallies from 2009 until 2015, raised hopes that the public voice will be heard. The fact that a left government didn’t take account of the referendum’s public voice, dissolved any hope for a political system’s change. “The day when the government voted for the third memorandum, there was no public reaction or rallies, and that reflects the feeling of public disappointment,” says Minas Konstantinou, journalist at The Press Project. As Minas explains, people’s reflexives didn’t disappear, yet it shifted towards the new issues the society is facing, like the immigration crisis. “This proves that that previous energy people had didn’t go away, it’s just that people engage with political and social issues in a different way now than before,” adds Minas.

“I just hope that one day, they will make me feel regretful for not voting ”.

STAMATIS LIMANIS

Nikos Kibaridis is a 22 years old student who voted for the first time at the referendum in 2015. “Voting at the referendum was important to me. It’s a historical event for my country and I wanted my vote to be part of the result,” he says. Nikos is part of the young generation that has been raised in the memorandums and austerity era. Four years after that vote, he found himself struggling in choosing which ballot paper to put in the ballot box. As he explains, he was trying to make a decision by excluding options, since he didn’t want to vote for a past government that had already disappointed him.

The European Parliament elections in May 2019 were not only an indicative forerunner of the dynamics of the political parties and the reason why the government announced general elections for July. Despite the fact that the elections were held the same Sunday as the regional ones, the participation was strikingly low, like almost always. The institution of the European parliament and its significance appears to be terra incognita. “Greeks consider Brussels too far away from them, that these decisions over there do not have a direct impact on them, ” says Minas Konstantinou.

When the new law for the copyrights issue was voted by the EU parliament, earlier this year, Minas found himself struggling as a journalist on how to present and explain the topic and he had to study a lot beforehand about the institution’s operations. As he explains, “there was no information or references from the Greek European parliament members, even if it was a big trend on twitter, and then people knew about that but only about that, nothing more about the topics that are being discussed in Brussels”.

The political system in Greece, especially during its glorious decades has been marked by the clientism between the politicians and citizens’ vote. As Theodoros Chatzipantelis, Dr, of Applied statistics at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki says, 25% of the votes go to personalities as candidates and all the other criteria, such as the party’s ideology and its program are less important, yet these criteria depend on the different forms of elections. Mrs. Penelope Foundethaki, Professor of Political Sociology and Comparative Politics at Panteion University School of Political Sciences says “that people lost faith in what was called democratic processes such as voting and participating to the commons ”, yet the Greek society got matured and became more self-criticised.

Without a doubt, the fiscal austerity and the memorandums era, followed by the 2015 year of changes have transformed political and social engagement of the Greek society which can be described in one clear word, apathy. “I just hope that one day, they will make me feel regretful for not voting, ” says Stamatis and he gets dressed to go and open his restaurant, earlier than usual. Elections day is always a busier day.

Vote from abroad

The high percentages of abstention do not indicate only a political disengagement of the public due to the last decade’s situation inside the country where about 11 million people live. According to the General Secretariat for Greeks abroad statistics, published in 2016, over 350.000 people left Greece to live abroad during the crisis period of 2010-2016. With Greece being one of the few European countries where postal vote from the diaspora is not applicable, the thousands of people who have the right to vote for the Greek elections can’t actually participate in them, unless they travel to Greece for the elections day.

“It is totally unaccepted for a European citizen not to have the right to vote for a government at any place of the world and to ask people to book a last-minute plane ticket of 500 pounds to come for two days just to vote,” says Nikos Stampoulopoulos, founder of the ‘New Diaspora’. Nikos, along with many other people both in Greece but mostly outside the borders of the country, are the voice of the Greek diaspora and its right in participation in direct democracy. ‘’This is a deficiency of democracy. All these people who can’t practically vote are part of the abstention’s percentages,” says Nikos.

The issue of postal or electronic vote for the diaspora has been discussed for many years yet, in 2019 elections these options were not available except for the elections for the European parliament. ‘’It’s totally unacceptable in 2019, with the progress of technology, not to have the willingness to use it for the people who live abroad, ” says John Ketsogiannis.

John has been living away from Greece for 14 years now but he is still trying to arrange his holidays according to the elections’ day in order not to miss it. The disengagement of the people towards politics in Greece is not a phenomenon eliminated inside the country. As Nikos explains, the younger diaspora generation, is more willing to travel to Greece to vote, they are still connected to the country. However, the people who live away for a long time, are continuously disappointed by the promises of the Greek politicians for the vote from abroad that they have distanced themselves from actively participating in Greek politics .‘’There’s the feeling that politics is mocking the Greeks who live abroad, ” says Nikos.

Political engagement has lost its past glory, or at least it has lost the glory of the populous rallies, the famous, populist leaders and the ‘politically coloured’ old traditional cafés, where political arguments and discussions were pushing the buttons. “As a nation, we have the mentality of arguing with anything that doesn’t agree with our view, ” says Nikos and as he explains, especially on social media, political discussions are still on the trends, yet for different reasons according to each group of people. “You see older people, especially on national issues, like the Macedonia one, expressing their view on comments, posting a photo with a national symbol… The political opinion always exists but not to such an active and loud way unless elections come,” adds Nikos.

Greece’s problem is not only the so-called ‘brain-drain’. The disability of a democracy to implement the law about the vote of its diaspora is a callus for the home of democracy, even that home is a plane away for some of its citizens.

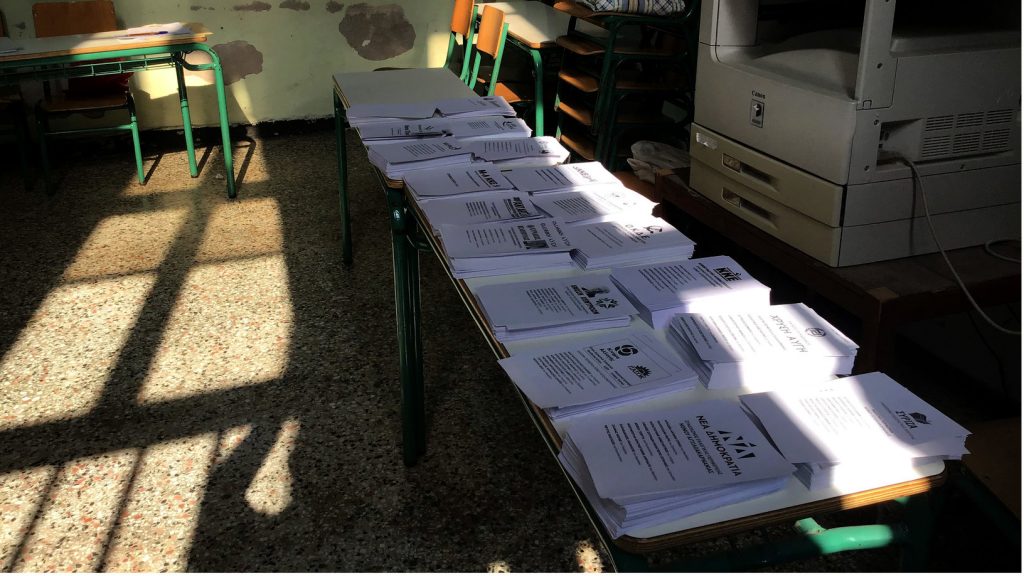

Featured image: Artemis Giannakopoulou