Japanese mixed-race athletes are appearing in the media spotlight more than ever with 2020 Tokyo Olympics taking place next year. Kazuki Tsuyukusa is no exception who is just about to shake up the sumo world.

It was a hot steamy day in Tokyo, with the sun glaring out of a clear blue sky. Out of nowhere appeared a six-foot man on a city bicycle – commonly known as mama chari (mama’s bicycle in English) – in bright blue yukata with a knot on the top of his head.

24-year-old sumo wrestler Kazuki Tsuyukusa reached out his hand for a shake and greeted:

“Dzień dobry”

which means “hello” in Polish. He kindly invited me to have ramen for lunch with him and his colleague from the same dojo or stable. Gracefully cooling himself with a traditional Japanese fan called uchiwa, he placed the order in Japanese in spite of having been given the English menu.

“Is this your first time coming here?”, I asked him in mild curiosity.

“No, I actually come here a lot”, said Kazuki.

“So, you’re a regular here, aren’t you?”

“Haha yes.”

He answered with a warm chuckle as if one classic awkward moment for mixed-race people just slipped through his radar. As we chatted on, interestingly he said he was a trilingual of Japanese, English, and Polish in the order of proficiency. After he slurped up a few bowls of ramen, we headed off to a local garden for the interview where he spoke more deeply about what it was actually like growing up mixed-race, aka hafu (from the English word “half” – as in “half Japanese”).

Kazuki was born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Polish father, with whom he moved to Poland at the age of five.

“My father first came to Japan as a student. He used to tell me that there were almost no foreigners living in Nagoya back then although there were some in Tokyo”, said Kazuki, “Every time he was on the train, people would stare at him in curiosity.”

Kazuki spent five years in Poland attending local schools and an international school, and then Prague in Czech Republic for two years. For junior high school, he moved back to Japan where he obtained education under the International Baccalaureates programmes. He then continued his education at none other than International Christian University High School – one of the most prestigious educational institutions in Japan.

“At ICU, there were so many people from different backgrounds. Most of the students there were returnees and hafus, so the Japanese students were a minority”, he said.

He believes that such environment with people from distinct backgrounds helped to a great degree in growing up as one individual of mixed race. Nonetheless, it is often said that mixed-race people are the target of ruthless questioning of their identity and ethnicity. Such identity and race questioning is what hinders their identity formation for many hafus.

So, has Kazuki encountered any obstacle growing up as a hafu?

“In Japan, I know they were not trying to be mean or racist, but I was often asked ‘where are you from?’ and was even told ‘wow you speak very good Japanese’”, said Kazuki.

“I think I am Japanese… and Polish. But maybe because of my non-Japanese appearance, even if they know I’m half Japanese, they still treat me like a foreigner.”

It was not only in Japan but also in Poland that he has had such experiences regarding his race. In Japan, the questioning towards him was a little more subtle with tilted heads as if part of a friendly anthropological case study of some sort whereas in Poland it was more explicit.

“In Poland, there used to be more people who made fun of Asians and I was called ‘Chinese’ and ‘Ching chang chong’ and stuff”, he explained.

“But I thought it was kind of funny”, he said laughingly, “I didn’t really get offended actually, maybe because I didn’t speak Polish very well back then and it was hard for me [to communicate with them]. But when you are a kid, it’s not much of a problem. You can just play soccer and make friends with them.”

In addition to his experience at ICU where he was surrounded by people who have been through similar experiences, his optimistic nature as a person also contributed to himself dealing with issues of identity and belonging.

“I have been through negative experiences growing up, but I don’t remember many because I’m optimistic by nature. Actually, I think being a sumo wrestler in Japan was a good decision for me as well, because people can easily recognise me.”

From his experiences in contact with people throughout adolescence, he says he has also developed an analytical eye to distinguish good people from bad ones and vice versa, so he can now wisely figure out what kind of people he can stay close to and should stay away from. By good people, he meant those who would try to understand his background and accept him just the way he is as a person.

While this shows that some people do not necessarily struggle with such issues of identity and race like Kazuki, many others still do. This leads to the question: what is the predominant factor in making the life of hafus in Japan so complicated in the first place?

“For example, in the United States and many countries in Europe, there are people of all races and there is no such thing as pure race especially nowadays”, Kazuki explained, “But in Japan, people can tell if you are purely Japanese or not straight away. So, sometimes you can stand out in a good way, but you can’t really fit in.”

He also pointed out that when you are young, the more different you look from others around, the more likely you will attract unwanted attention which will eventually lead to the receiving end of bullying.

On the contrary, once you have grown up, you will find yourself in the spotlight of admiration and jealousy from people saying “Oh I wish I was born as a hafu as well” and putting you in a stereotypical frame of a cool foreigner, leaving you feel subtly alienated or “other-ed”.

Kazuki feels that this cultural and societal contradiction can be attributed far back to the history of Japan as an island. So, who and what is to decide that someone is Japanese or not Japanese?

What It Means to Be Japanese

From the late 1960s to the 1980s, a study called Nihonjinron (theories of the Japanese or Japanese-ness in English) became prominent within both academic and business circles. Typically, Nihonjinron supports ethnicity as a basis for national identity and emphasises the alleged uniqueness of the Japanese culture and social consensus.

This is closely associated with the time when the emperor of Japan in the Meiji period idealised cultural and racial homogeneity as the foundation of the country in 1868.

Such measure implemented by the Emperor had a destructive impact on the life of the Ainu – an indigenous people of Japan and Russia. The Ainu were automatically granted the Japanese citizenship, “legally” dismissing their status as an indigenous group which had been an integral part of their identity. They were forced to learn Japanese and adopt Japanese names. Such marginalisation of the Ainu manifests the long history of cultural and racial exclusiveness of the country.

So, is the population of the mixed-race in Japan increasing or decreasing?

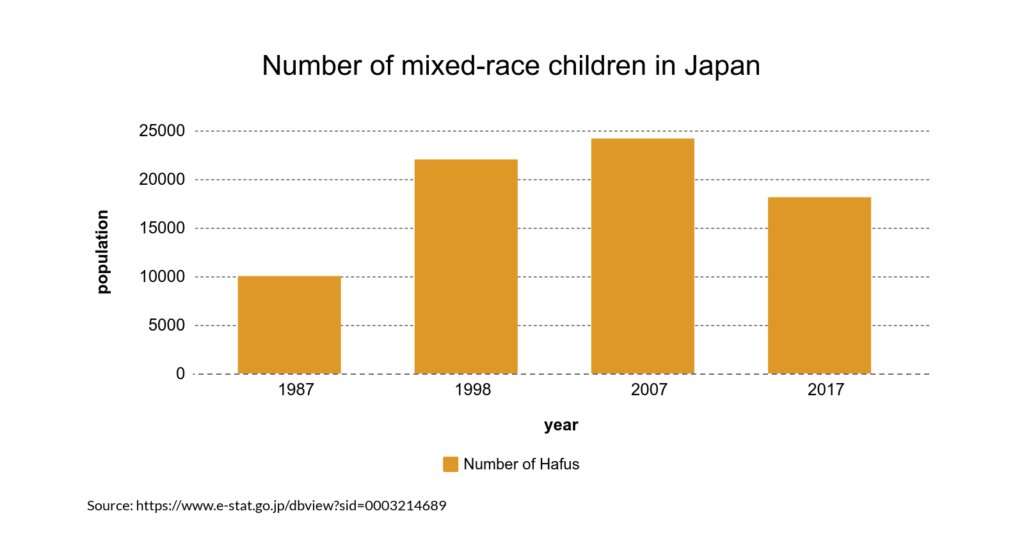

A demographic study by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare shows that the number of children born to a non-Japanese parent has risen with fluctuations over the last 20 years. However, the number has been dropping since its peak in 2006-2007.

From 1987 straight to 1998, the number of hafus never ceased to rise and more than doubled from 10,022 to 22,021. Until 2005, the population witnessed a fluctuation between 21,000 and 22,000. From 2006 to 2007, the figure reached its peak of over 24,000, making it the record high in history. But there has been a gradual decline in the number since the peak in 2006-2007 up until today, currently at about 18,130.

The side note here is that the actual population of mixed-race children who were born to a Japanese parent and a non-Japanese parent is uncertain because the figure of those born outside Japan is not included. This means that the actual population of hafus will exceed the figures compiled by the government by far.

In addition, the Ministry began collecting data on international marriages in 1965, but the nationality of father and mother was not presented from 1947 to 1986, except for the case that the father was a foreign national and the mother was a Japanese citizen. It was only from 1987 when the nationality of parents started to be universally classified.

The Impact of New Immigration Policy

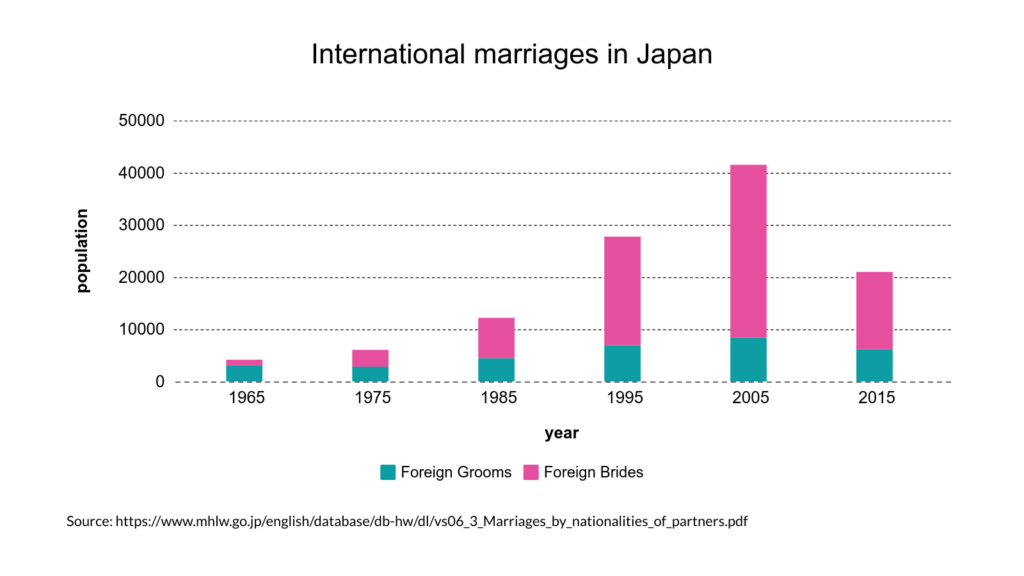

The dip in the number of the mixed-race children may as well be in parallel with the dip in the number of international marriages in Japan. According to another study by the Ministry, the country had a total of 620,531 couples tying the knot in 2016, and 21,180 of which were international marriages. This means that one in every 29 couples was between a Japanese citizen and a foreign national.

In 1965 when the Ministry began collecting data on international marriages, there were only 4,156 cases of international marriage between Japanese and non-Japanese citizens. The annual total had reached 10,000 by the early 1980s and continued to increase by 10,000 almost every decade, reaching 40,000 in 2005.

In the following year, it peaked at 44,701 only to start heading downwards to below 30,000 in 2011.The proportion of international marriages has practically halved from its high point of 6.11% in 2006 to 3.4% in 2016.

Revisions made to the Immigration Policy in 2005 have been addressed as a major cause for the significant decline in international marriages. The measure came at the time when Filipinas came to Japan as “entertainers”, illegally obtaining visas through fake marriages with Japanese men so that they could financially assist their families back home.

Revisions were introduced in the attempt of improving public safety by tightening requirements against them. As Filipinas account for a large proportion of foreign spouses in Japan next to Chinese, the stricter immigration policy resulted in the overall decline in the number of international marriages and thus the number of hafus likewise.

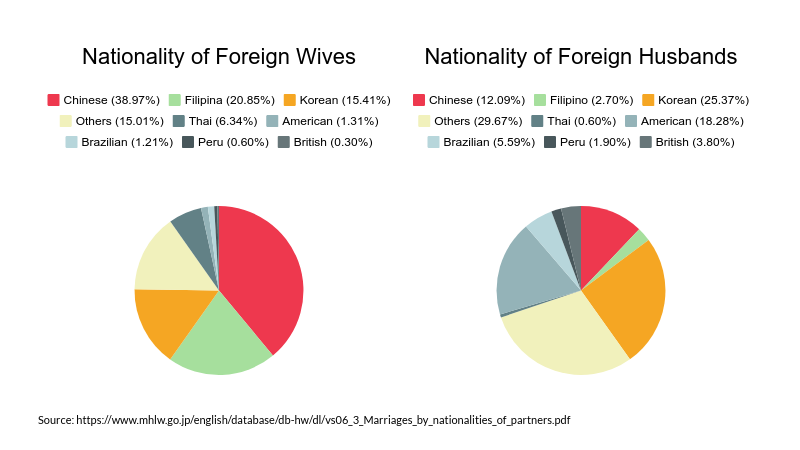

The Ministry also reported that about 80% of international marriages in 2015 were between Japanese grooms and brides from other Asian countries such as China topping at 38.7%, the Philippines at 20.7%, and Korea at 15.3%.

Interestingly, however, in the same year, observing the annual trends of first-marriage rates between Japanese grooms and non-Japanese brides by nationalities, brides from the UK demonstrated the highest rate at 88.6%, followed by brides from the US at 82.4%.

In comparison, the first-marriage rates of brides from China and the Philippines saw a decline from 67.9% and 93.8% in 1995 to 48.6% and 66.7% in 2015, respectively.

These statistics demonstrate how many of the international marriages back in 2015 involved foreign brides who were already married before or at the time of the marriage with the Japanese grooms, and the proportion plummeted after the new Immigration Policy came into effect.

The statistics also suggest that, for first-time marriages alone, there are increasingly many more Japanese grooms choosing to marry brides from the UK and the US over those from China and the Philippines. This means that there will be even more mixed-race children who would be visually distinct from what is described as “ideal” in Nihonjinron.

Japan in the years and decades ahead

While the government has been trying to build healthy, multicultural and multiracial communities since 2005, the image of homogeneous Japan ‘accepting’ or ‘welcoming’ foreigners still remains a strong element around this discussion.

There are many more issues that hafus are more aware of than others, which can also be a source of negative experiences for them. Nevertheless, in quest of their own place and their own sense of belonging in society, hafus in Japan may have the capability to be a great force to shape a new Japan.

“I think the society is becoming friendlier to hafus as well as foreigners”, pointed out Kazuki, “For example, now you see a lot of foreigners working at convenience stores.”

He also referred to the growth of Japan’s ageing population and said that the country would have to start accommodating even more foreigners in the years and decades ahead, which will likely increase the population of hafus as a consequence.

This month, famous TV presenter Christel Takigawa – who is half French and half Japanese – made a public announcement that she got married to politician Shinjiro Koizumi, one of the sons of former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi. If Shinzo Koizumi took office as Japan’s Prime Minister, this would certainly open the country’s doors even wider to racial diversity.

With a growing number of mixed-race celebrities, TV personalities, and athletes in Japan including Kazuki himself, when hafu children today are in their 20s and 30s, we will then really start to see how far we will have come.