Chinese network literature has become a publishing phenomenon labelled as grassroots fictions posted online, why is this form of literature attracting so many readers?

With a speed of 15Mbps, a barrage of codes is, from the Red East I Satellite, through clouds layer upon layer, pouring into the crowds on 116’E, 40’N.

0100011100…Roaming data is twisted into a brand-new system of literary creation and appreciation – network literature.

The era of Internet has made electronic reading no longer a wonder. But Chinese network literature stands out as something else that doesn’t just highlight the upgraded reading device.

“The basic distinction between network literature and traditional literature lies in the content rather than the medium,” says Liting Zhang, an editor of traditional literature. “The story settings of network literature are usually whimsical and eye-catching, and contents are very market-oriented.”

Fantasy and Romance fictions once manipulated the market in the early age of Chinese network literature. But new subject matters, including Time-travelling, Nirvana Rebirth, Ghost stories and so on, emerged as bamboo shoots after a spring rain within a couple of years.

In the core of these subjects is a void of reality. Network literature sells unrealistic stories to amend the imperfection in reader’s real life.

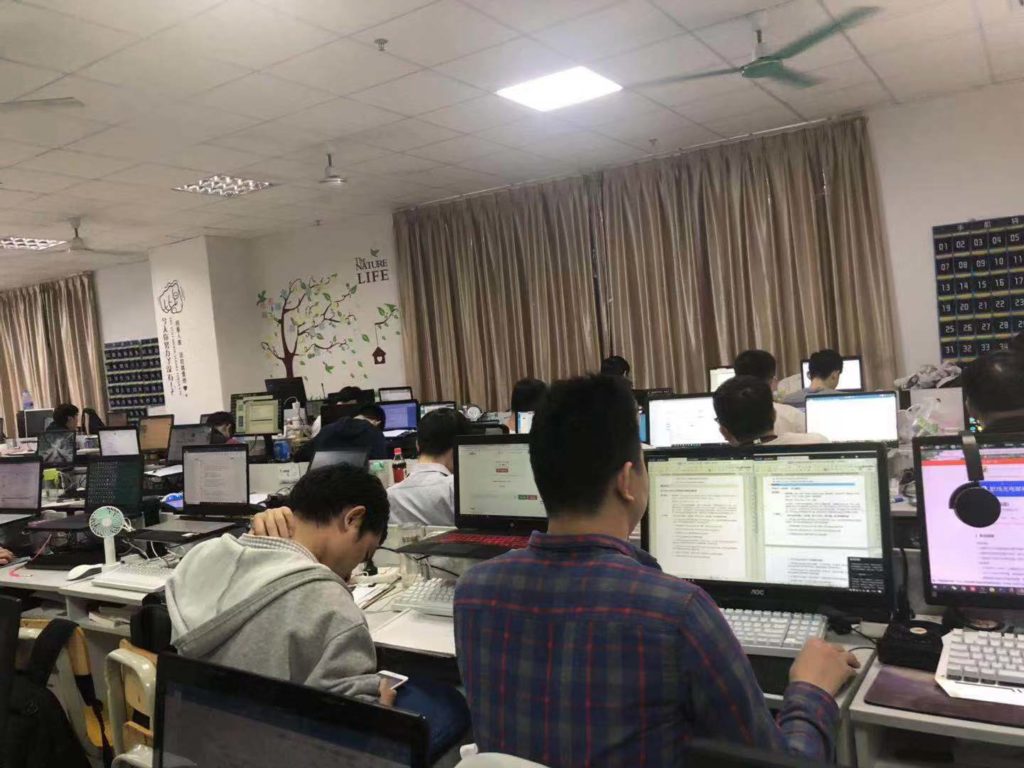

As social class rigidity gets serious, network literature provides desperate ordinary young people with a surreal enjoyment of fantasy where they can be shining protagonists.

Hao Li, a literary critic and traditional writer.

In the world of network literature, an ordinary girl becomes the queen, a miserable orphan is meant to break the curse on him and revenge for his parents, Prince Charming abandons everything for the poor girl he falls in love with…

These turn out to be what readers want. “Every style of writing or content owns its audience base,” says Huanchu, a network literature author. “My readers follow me for my Time-traveling fictions and the Mary Sue style. Most of them are teenager girls, as boys usually prefer Eastern and Ancient Fantasy.”

Network literature in China has become a publishing phenomenon with a huge audience pool. According to Network Literature Development Report 2018, the number of network literature readers has reached 0.4 billion, which makes up 50% of total Chinese net citizens and about 35% of the whole population.

Wuxin is a member of the army. Having read network literature for seven years, she lively remembers her frenzy once, “It did happen a lot when I stayed up till early mornings reading online novels that I found very interesting and engaging.”

Providers exist where demands are. Countless writers are diving into this huge business.

“Network literature is more dynamic and is attracting more talents to the writing career,” says Huiwen Zhang, a freelance traditional novelist, “as the door for traditional literature is usually locked due to its high standards. But network literature opens up infinite roads ahead.”

Known as Tiantian Chen in the real world, Huanchu already has three finished novels published on Yunqi Web, the network literature platform owned by Tencent company – one of the strongest commercial giants in China.

Estimating on the number of her fans, she smiles: “I’m assuming 110,000 loyal readers, and more than 600,000 out there who don’t subscribe my chapters.” However, she only describe that as a mediocre level.

Maybe “110,000” wouldn’t sound intimidating anymore if one had a look at the ecology of fans in network literature community. Young readers willing to spend time and money on network literature have shown an amazing consumption capacity.

The average monthly subscriptions for an online novel reached one million by 2018, which means each online novel had more than one million readers paying for it.

I think, in essence, it was technology and commerce who had changed human’s lifestyle that eventually stimulated network literature to occupy the market. Reading online with countless dazzling options is indeed much easier than picking up books in bookshops.

Huiwen Zhang, a dedicated traditional writer

Convenience is put forward by many online readers as their chief considerations for choosing network literature. “Online reading is convenient; you don’t have to bring a heavy book with you everyday,” says Wuxin.

The modern society has crumbled a fast-food lifestyle into people’s mouths. Then “traditional literature which demands time to contemplate and appreciate seems too slow for the fast-paced society,” says Huiwen, who has devoted herself in traditional literature creation for years.

Network literature showed up as the paradigm of an adaptable literature, with its amazing accessibility and productivity, where writers offer customised products to given readers.

But how could writers know what readers want?

Sharing a close relationship, readers and writers do know each other very well in network literature.

“Network literature manifests itself probably in writer’s way to communicate with reader,” says Huiwen. “Online authors hold constant conversations with their readers, while traditional writers rather stay quietly behind their words. ”

On network literature platforms where writers publish their works, chapter by chapter, day by day, readers sign up and comment whatever they feel like. Writers then recognise their preferences and give responses.

Conversations between readers and writers within network literature set up a stage for the market to play on, when writers start to consider readers’ demands seriously during literary creation.

“Literature has been commercialised too much online,” says Liting Zhang, not only in the way it engages the large group of readers, but also in that the capital is expanding into other areas.

Chinese network literature is a highly value-added business magnetising investments from all directions. Apart from payments for reading itself, money comes from various peripheral products, such as online games, advertisements, and literature exports to TV and film industries.

“Being linked with television is another network literature’s embodiment of commercialisation,” says Huiwen. “Television is the entertainment that highly caters to the market, which doesn’t match the artistry that traditional literature emphasises.”

Money versus artistry. Yes, right here, it is where all the “pride and prejudice” comes from.

“To be honest, I’m not familiar with network literature,” Huiwen sinuously expresses her impunity on the literary value of network literature. “I tried to read some, but as a literary creator, I felt difficult to engage with empty contents and raw uses of language.”

“But surely there’re some good ones,” she adds. Yet some others are more straightforwardly critical.

“I don’t want to be any biased against network literature, but I’m saying, it is indeed off traditional literature’s league,” says Liting, an editor holding high standards of content selection.

Arguments also arise from unbalanced treatments. Grassroots online writers nowadays are earning a lot more than traditional writers who are seen as intelligent elites.

Throughout the creation of Huanchu’s three network publications, she earned averagely $1,500 per month whose maximum could reach $4,500, which far surpassed Chinese monthly per capita of $325 in 2018.

Yet Huiwen Zhang, with tens of novels published on famous literary journals and four collections published in hand, can’t guarantee a number like that. “I’m far behind,” says she.

However, “network fictions are actually quite cheap and more affordable for the young, because you can choose whichever chapters to buy and cancel subscriptions at anytime,” says Wuxin, a loyal reader of network literature.

“Each of my readers only have to pay 0.05 yuan for 1,000 of my words,” says Huanchu. “But the large number of them and my daily outputs sum up to a big business.”

High profits often come with high risks. Network writers’ incomes are usually unstable and unpredictable. That’s why some online writers don’t consider their writing as a proper job, and secure themselves with other jobs instead. According Xinhua Net, more than a half of total registered network work writers are doing part-time, while full-time writers only count for 47%.

Graduated from Tianjin Industrial University in 2018, Huanchu is now striving for a job in the IT field. “That was my major in the university,” says she,“hard to say I enjoy it though. You have to make your life with a stable job.”

“There is an interesting phenomenon today,” Huiwen brings up another contradictory fact, “that popular online writers take getting published in traditional print literature as an ultimate honour. That is to say, irrespective of economic successes, they still want the approval from traditional literature.”

Online writers sometimes deprecate themselves. Huanchu shows a lack of self-confidence in her writing skills, “I think traditional literary creation focuses more on craftsmanship. I’m not proficient in using beautiful language or protean methods to create atmosphere in stories.”

Like a kid striving to grow strong enough to be independent, network literature compromises with traditional literature. But in any mother-and-son alike relationship, son’s growth won’t threaten mother’s future.

“Traditional literature doesn’t have to change,” says Liting. “Because as I mentioned, It is the content rather than formality that matters. Traditional literature works can be put up online as well, but it will still be the traditional literature that we know. Only if it doesn’t lose its nature, the market won’t go.”

Huiwen admits certain impacts but doesn’t believe serious literature creation will be pushed to precarious situations: “I’m sure some people will give up this career considering money, but many writers like me prioritise passion for literature.”

20 years ago, network literature was dismissed by highbrows as a cancer for Chinese literature, but now it is leading Chinese young generations to the NEO age of reading.

Maybe not just Chinese young generations are immersing themselves in network literature. Go check out WuxiaWorld, the biggest English website of Chinese network literature, you will see an ever-expanding oversea market. Ancient Fantasy network novels have successfully caught foreign eyes.

Network literature is the market’s choice. Taking traditional literature down or not, it has put its name on the history page.