Over 1/2 of Chinese Internet community is consuming original fictions published online, known as network literature, just how is its development threatened by the strict censorship in China?

Reposted for 95,000 times on social media, Jinjiang Literature Community posted: “As a response to ‘Jing Wang’ Action, Jinjiang hereby declares that we are closing our website temporarily to operate a thorough content self-censorship and and technology upgrade.”

Jinjiang Literature website, serving more than 3.4 million daily active users who view its web page for 0.3 billion times everyday, was then shut down for 15 days.

“Winter is coming – for the whole network literature industry,” says Yanming Huang, the CEO of Jingjiang, on 1 August 2019, three days after the website’s back to operation.“ Now we have to think twice before leap and hold each other together for warmth.”

Network literature is a new form of literature which, within 20 years, has grown from unsystematic online-published amateur fictions into a big publishing business in China, read by a half of Chinese Internet population.

Hundreds of thousands of contents are posted on network literature platforms. From romantic love stories to dark revenge plots, readers immerse themselves in the fictional world created by hard-working online writers from unknown backgrounds.

Jinjiang Literature Community is a leading powerhouse of network literature in China. Launched in 2003, it has published 3.23 million online novels that are made up of 7.82 billion characters.

Yet under the particular post of Jinjiang declaring its closure, the ZERO comment seems a terror of silence. Jinjiang Literature community probably blocked all comments out because “Jing Wang” Action was involved. Although censorship has been an accepted fact among Chinese literature communities, this action is definitely an upgrade move.

“Writing, no matter what kind of writing, should obey the public order and respect good customs,” says Hao Li, a famous literary critic in China. He believes that “the review of literature is necessary”, while the basic rules should be “not to insult any particular groups or races, and not to do malicious incitements.”

Network literature, as a literary formality, is no exception under the burden of censorship ever since its birth.

The principle is: no porn, no violence, no politics. For example, if you mentioned a historic figure in your story, even though it was just a name without any descriptions, it is possible that the whole chapter would be blocked.

Huanchu, an experienced network writer

This kind of censorship was mainly conducted by computer systems. Programmes were written into the design of network literature websites, which would automatically filter key words in the texts for editors.

But “artificial intelligence makes mistakes”, according to Huanchu’s writing experience. Even the most advanced IT can’t be completely protected from bugs, which leaves a space for network literature to breathe.

“The system can’t recognise all targeted contents from the numerous updated chapters,” says Huanchu.

It was widely agreed that network literature was under a looser control than traditional print literature where a mature system of censorship had been established.

“Censorship in traditional literature was stricter,” says Wuxin, a reader of network literature for nearly a decade. “Organisations like the State Administration of Radio Film and Television focused more on traditional literature rather than on network literature, in the past.”

Administration of Radio Film and Television in Beijing. It contributes in watching and managing cultural and creative contents in China. Photo: Public Domain

But what happened to Jinjiang is clearly a signal, warning the industry to behave itself in the upcoming new age of censorship. The line is now pushed forward more and more.

Back when a stable structure of censorship hadn’t been developed yet, self-censorship was the chief mean for network literature to defend itself in front of legislations.

However, self-censorship in the past was to certain degree problematic, as unspoken strategies to avoid restrictions whispered among online writers still worked.

“Because government is tightening up its control on the creative industry recently,” says Huanchu who constantly keeps an eye on pop culture. “Some so-called unhealthy content selected by the system while neglected by online editors previously can not slip through anymore.”

This clever self-protection from the official watch cooperated well with the low thresholds of network literature creation to burst network literature in its early age.

“Network literature gives many people the opportunity to create and publish freely,” says Huiwen Zhang, a traditional writer, while “there are more standards and thresholds on traditional literature’s way of seeking publications.”

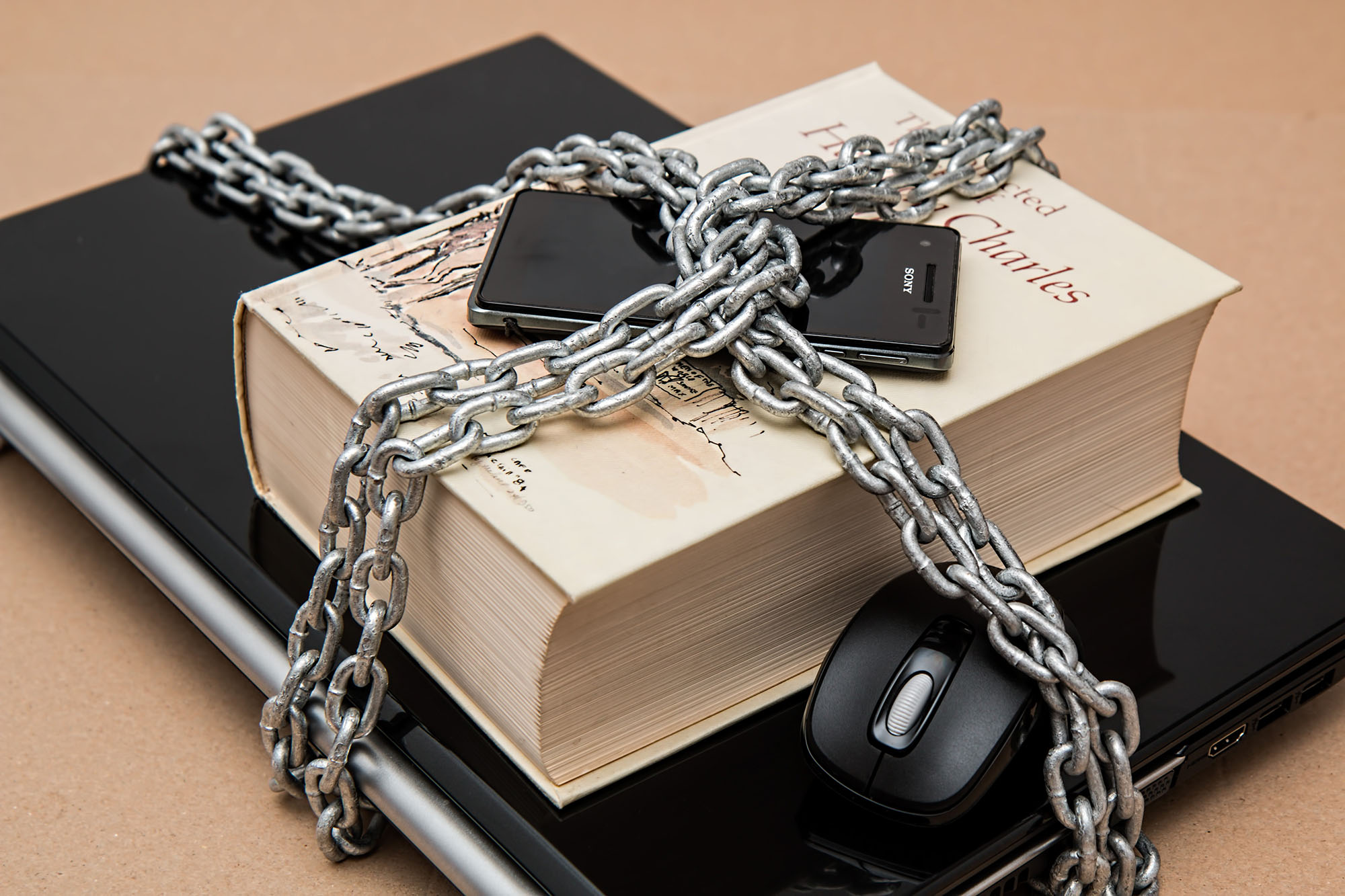

An irony came when free creation, the fertility for network literature, was taken away. Chinese network literature clearly feels the chains on it tightened.

Legislation is now targeting network literature.

Liting Zhang, a literary editor

Network literature is like a piece of polygon paper, being cut off a bit, then a bit more, finally into a standard square, by the visibly-sharpened knife of censorship.

At this particular moment, the whole literature industry, not just network literature, starts to feel an aching beneath the skin. Red light on – censorship shouldn’t go any further.

“It should not go beyond the limit,” says Hao Li, “especially should not be the restriction to imagination and creativity, either for traditional literature or online novels. Censorship system should preserve a boundary that is open to discussion.”

Frozen air has been felt from different spaces and on different levels. Complaints strongly flow on the social media. Hashtagged as “Jinjiang Literature Community” are some posts on Weibo:

-“The censorship on Jinjiang is completely a rigid uniformity.”

-“It is just ridiculous to accuse the word ‘groaning’ of conveying sensuality if it is used to describe two kids playing together.”

-“The environment now is bad. My chapters could be locked for groundless accusation of pornography.”

It’s not clear whether writers or readers posted these, but only the tricky situation network literature is currently facing.

Strict censorship “largely reduces the enjoyment of reading,” from Wuxin’s perspective as a reader. Yet with no signs of stopping, censorship is even encroaching the TV industry, as network literature accommodates TV dramas with countless story bases.

Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace was one of the most popular Ancient Palace Intrigue story on Jinjiang Web. In the TV drama adapted from it, shots of characters being tortured by a cruel death penalty in the palace were all edited off.

“This was supposed to be a highlight moment of Ruyi’s revenge!” Says Zhanshi, a fan of the novel Ruyi’s Royal Love in the Palace. And this obvious jump cut confused the audience who hadn’t read the novel before.

Just as the highlight moment of Ruyi taken off from screen, the highlight moment of Chinese network literature is likely to be erased. On the canvas of free creation, network literature is losing its last colour block.

After the administrative punishment, the web page of Jinjiang seems no different from its previous look. And the comment section of that Weibo post declaring its temporary closure remains a blank space.