Since 2010, the Chinese government has launched a series of policies to support children in rural areas through education, has this government initiative really helped the lives of poor rural children?

One old, primitive adobe house with two layers. The biggest crack has been blocked by rags and straw. When the rain outside has stopped, it is still seeping through the wooden roof. Appliances in three rooms are quite simple. They are beds, tables and the small light hanging on the roof. No computers, no televisions.

This is Hufeng’s home in Shannxi province, Chenggu, on the hillside of China’s Qinling Mountains, the geographical dividing line between Northern and Southern China. Last year, the annual family income was lower than £300, typical of a poverty-stricken household in the area[1]. Poor rural families are defined as having an annual family income under £331 (2875 RMB), according to latest provincial standards reported by TenCent media.

Hufeng’s mother has lived in this mountainous area decades of years. She regards education as the only way which could help her children step outside the backward place. “We parents did not receive any education. We hope he is able to get into the high school. Schooling is my child’s last chance of getting rid of mountains and poverty,” she said.

In China, mountains often have connections with poverty. In 1992, the leader of the Communist Party of China, Deng Xiaoping put forward that the development of coastal areas including Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang is of a high priority. Thirty years passed, China’s coastal areas have thrived a lot, while the rest areas, especially those with geographical complexity are left behind.

The Qinling Mountains is one of China’s major mountain ranges. It runs west to east and is more than 1,600 kilometres (994 miles), stretching across China’s three main provinces, Gansu Province, Shaanxi Province, Henan Province. Per capita disposable income of these provinces is around £600 lower than China’s average level. In 2018, rural residents’ per capita disposable income in Shanghai Province is nearly three times as much as that in Shaanxi Province, according to annual report from National Bureau of Statistics of China[2].

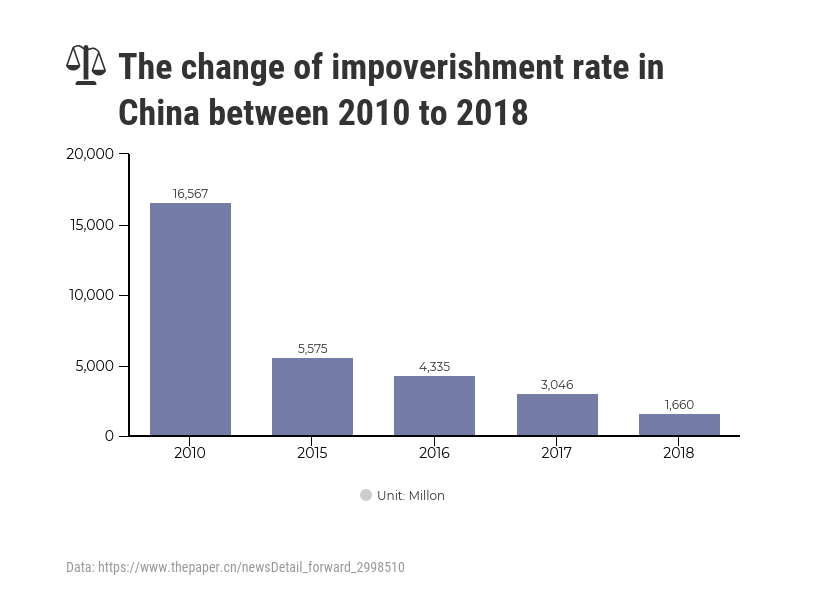

By the end of 2018, there are still 16.6 million poverty-stricken population, like Hufeng’s families, according to statistics from National Bureau of Statistics 2019[3]. The Chinese government aims at eradicating extreme poverty population by 2020 and one of slogans said, “before breaking through poverty, get rid of illiterates.” From this idea, the state has launched an education-based poverty reduction project since 2010 for helping children in rural areas through education.

Now, Hufeng is a 15-year-old student in Grade 8 in Chenggu Shuiwei Central School. Next year is the time for Hufeng to attend the high school entrance test (Zhongkao). However, “He is at the bottom of the class ranking and could hardly pass the high school entrance examination,” said Hufeng’s English teacher as well as the principal of the school, Wang Yun who has been working here for seven years.

Hufeng’s hopeless academic performance seems not the responsibility of financial obstacles. Actually, his mother almost does not need to invest in child’s schooling before higher education. Since 2008, the Chinese government has universalized the free compulsory schooling (primary school and middle school). Meanwhile, as part of the education-based poverty reduction project, students in rural areas can have state-funded free lunch. All typical poverty-stricken households can receive extra £144 (1250 RMB) from the local government annually. When poverty students step into the stage of high school, they are still exempted tuition fees, textbook fees and receive subsidy £354 (3000RMB) every year, according to a piece of news from local government[4].

All these policies are undertaken effectively but they could just guarantee a quite basic life. Hufeng today’s lunch is stir-fried pork with vegetables and spicy Tofu. He is not a picky eater and he eats up. Each free lunch is with two greasy courses and rice, all in a large bowl. “Meals are generally OK but sometimes a little bit overcooked or undercooked,” said Hufeng. After lunch, he goes back to the school dormitory and shares a single bed with one of his classmates. Each room has five bunk beds and some of them are even shared by three students.

All financial aids are necessary for Hufeng’s mother and she thinks these have been enough. “Money has not been a problem. His education does not cost too much. It is different from my time,” Hufeng’s mother said. As a person born in 1970s, Hufeng’s mother did not receive any education because of poverty. The government gradually adopted the market reform after 1978 and gave up totally fee-free education. As a result, at that age, education opportunities of part lower class were deprived directly because of the unaffordable expenditure.

Now, the situation has become different. “Less and less dropouts are directly due to financial difficulties. However, economic support is just the first small step. The problem has turned to the low educational quality and outcome in rural areas,” said Cai Fang, the researcher of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of Rural Development.

Last year, only half of students in Chenggu Shuiwei Central School passed the high school entrance examination. It has been the best performance they have ever made. This is partly consistent with the figure of 40% high school admission rate in rural residents, which shows 20% lower than the rate of urban’s[5], according to statistics from China’s largest education information website, China’s Education Online.

The imbalanced educational development is the result of uneven resources. “We lack teachers,” said Wang Yun, with a deep sigh. She is responsible for English courses of Grade 3, 4, 8, 9 and has to bustle around different classrooms throughout the whole day. Her table piles students’ English spelling homework, textbooks, and timetable of several classes.

The Shuiwei Central School gathers students from surrounding four villages and provides courses ranging from kindergarten to Grade 9 (middle school). “We have a wide range of students and thus we need teachers who could teach different levels,” said Wang Yun. Under this situation, every teacher in Shuiwei Central School has got used to being multifunctional.

Actually, the shortage of teachers in rural compulsory education in China has been alleviated. According to the China Rural Education Development Report 2019[6], the ratio of teachers to students in rural schools has increased continuously. In terms of the percentage of teachers with bachelor’s degree in middle school, the gap between urban and rural areas has lower 2.5% than 2016 but it is still 10.3%.

The majority of qualified graduates are unwilling to teach in disadvantaged places. Statistics from ScienceNet[7] shows that the average percentage of the graduates from China’s top six normal universities who chose to teach in rural schools is only around 4%. Their preferences are highly homogenous, that is leading urban schools. Other graduates will not regard schools in remote ears as the first choice either. Meng Xin, a recent undergraduate from a leading normal university, chose to be a teacher in the capital city. She said, “I born in a township and I am not willing to live in less developed areas any more. Working in the city, I can earn more money since I have more opportunities to do part-time private tutoring. Meanwhile, the career prospect is promising.”

In order to increase the number of teachers and satisfy needs of rural schools, the state cooperates with China’s 170 universities for selecting students to be volunteer teachers and allocating them in remote areas[8]. These ten years, nearly 10,000 undergraduate students went to more than 400 rural primary and secondary schools in 20 provinces.

The way Chinese government used to mobilize undergraduate students’ enthusiasm of being volunteers is not limited to financial benefits. Additionally, if undergraduate students are qualified to be volunteer teachers and spend one year on teaching children in remote areas, they can obtain the admission of being a postgraduate directly and do not need to pass the entrance examination. “Making infrastructural change is easier. However, people are hard to be manipulated and they need such incentives,” said Cai Fang.

Finally, the mechanism works, volunteers come to these tiny, quiet, poor schools. There are two volunteer teachers in Chenggu Shuiwei Central School at the moment and they are going to leave this September for pursuing master’s degree. Tang Jiayin, the undergraduate in Aircrafts Design from Northwestern Polytechnical University and is the teacher of Grade 9 Physics, Grade 3 Math. He said, “I love these lovely children, but I have never thought I would stay here and be a real teacher.”

Despite these volunteer teachers are temporary, they are able to open a window of more possibilities to students. “Tang is my favorite teacher since he can always bring new lecture modes, teaching materials to us,” said Hufeng. He rose in pitch suddenly and smiled happily.

These young, creative volunteers are keen on helping children know more about the outer world. This semester, Tang Jiayin invited 25 lecturers, professors of aerospace from his university and one colonel from the air force to the school for teaching basic knowledge of aerospace, airplanes, military to children. They also donated more than one thousand model airplanes and hundreds of books to the school. “Students are very interested in these knowledges and they are quite excited. Without us, teachers here will not and are not able to hold such event,” said Tang.

Another volunteer teacher from Northwestern Polytechnical University, Li Landi, is children’s Music teacher now. “Every time I get into the room with my guitar, their eyes are shining,” Li said. The school has never had a Music teacher before.

However, what these students needs most is not abstract “horizon” but the improvement of academic performance. “Professional things still should hand over experts,” Cai Fang said. Volunteers have never been trained professionally. Tang has found teaching courses of Grade 9 is a little bit difficult. He said, “I need to spend a whole night on preparation. Sometimes, when students asked me questions, I did not really know. I would say, I was busy at the moment and I would help you later.” In addition to this, these volunteer teachers just stay the school for one year. “The mobility of teachers is quite high. Students need to get used to them continuously and it is hard to help students form long-term studying habits,” said Wang.

In some places, school heads as well as parents think volunteer teachers are redundant and a waste of money[9] since the local government needs to pay for their basic expenses, according to a piece of news from official news agency, People CN. Actually, after Tang and Li’s leaving, the Shuiwei Central School will not have volunteer teachers any more since the local government refused to cover their expenditure. The university decided to quit the cooperation.

It is a piece of bad news for the Shuiwei Central School and Wang Yun has begun to worry about students’ future. “Without volunteer teachers, things become worse. I have not known where students’ Physics and Math teachers are,” she said.

After all, what the state has done is better than none. “The government is trying to compensate the inequality during the social rapid development. Things are getting better but it is a long-term battle. Also, changing children’s life chances need the joint effort of parents, schools, the local government, the national government,” Cai Fang said.

For Hufeng, without his favorite teacher, Tang, he feels more hopeless, but he could just live and study as usual. He goes home every Friday, taking one-and-a-half-hour coach and walking along sinuous mountain roads for 30 minutes. The first thing he needs to do is cooking dinner for his mother and grandma. On Saturday and Sunday, he climbs to the mountain for picking a sort of Chinese traditional herbal medicine, which could be sold to the government. However, the price of this year has been half lower than that of last year.

Hufeng’s mother is still looking forward to that Hufeng’s academic

performance could improve and pass the high school entrance examination. However,

both Hufeng and his mother do not know how to achieve it.

[1] https://xian.qq.com/a/20141225/013902.htm

[2] http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexch.htm

[3] http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-02/15/content_5365994.htm

[4] http://www.li-xian.gov.cn/zwgg/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=53680

[5] http://chuzhong.eol.cn/sx/sxzk/201311/t20131128_1045475.shtml

[6] http://www.sohu.com/a/293038936_498142

[7] http://news.sciencenet.cn/htmlnews/2018/8/416754.shtm

[8] http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/201905/t20190514_381926.html

[9] http://paper.people.com.cn/mszk/html/2012-08/13/content_1099415.htm