The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found that the right to culture is fundamental for Indigenous women. How can a return to Indigenous traditions prevent violence against them?

In 1966, a Cree woman’s body was found in the middle of a frozen lake in Northern Alberta. It was Sandra Lamouche’s grandmother, one of countless unsolved murders of Indigenous women in Canada.

“My mother was 10 at the time,” says Lamouche, who grew up in Slave Lake, Alberta. “Her father was a trapper and spent his time out trapping, so she grew up very much on her own. She felt like she didn’t have a lot of support.”

Growing up off of the reserve, Lamouche felt she had lost the connection to her Indigenous roots. “The community, the land, my relatives. And culture.”

It wasn’t until Lamouche began studying at the University of Lethbridge and became involved in the grassroots movement to heighten awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, that Lamouche began to re-establish that connection.

“I didn’t know at the time that my grandma was an unsolved murder,” she said. “I started advocating and it was after that I learned what had happened. The effects of [the murder] continue to be revealed. I don’t think you could ever know all the ways its changed my life.”

Within many Indigenous communities, the right to culture is understood as including the ability to practise and pass on cultural traditions, language, and ways of relating to other people and to the land. For Lamouche, her family’s right to culture was violated through the residential school system imposed by the Canadian state.

“It was the destruction caused by colonization and the day schools my family attended,” says Lamouche. “That destruction was the loss of culture, the loss of family and community ties.”

Kim Anderson, the Canadian Research Chair in Indigenous Relationships and a professor at the University of Guelph, agrees that the right to culture is fundamental for well-being.

“The uptake in Indigenous cultural practices is important for wellness and well-being for the individual as well as the community,” says Anderson. “Reclaiming these practices is critical to well-being on the whole and ending violence against women is part of that.”

Culture, says Anderson, also helps to reinstate gender equity.

“We need to get back to the gender equity principles that Indigenous people practiced and lived by. How do we reinstate those so that we can have more violence-free societies going forward?” says Anderson.

The recently concluded National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls found that violation of cultural rights disempowers Indigenous people, particularly women, through racism, dismissal and heavy-handed state actions that seek to impose systems on them.

“It is also helpful to start calling out what is the breakdown of those traditions that colonialism caused that we need to address,” says Anderson.

On the other hand, the role of culture in healing was a key element of what many Indigenous witnesses to the Inquiry identified as areas in which their loved ones could have found comfort, safety, health and protection from violence.

For Lamouche, her own healing came in the form of Indigenous hoop dancing. Hoop dancing is a form of story-telling through dance. An Indigenous hoop dancer uses hoops to create shapes as they move to music—the hoops represent designs, symbols and animals.

After struggling for years with “identity, self-esteem, making bad choices, alcohol and drugs,” Lamouche began learning about the hoop dance. “Culture has led to my sobriety,” she says. “With the hoop dance, it changed my life.”

For many Indigenous groups across Canada, re-establishing the connection to culture has become a fundamental tenet in preventing violence that is experienced in their communities, specifically violence against women.

This is known as Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK), or “storytelling; ceremonies; traditions; ideologies; medicines; dances; arts and crafts or a combination of these” according to the Native Women’s Association of Canada. ATK is used by Indigenous groups across Canada to help prevent violence in their communities.

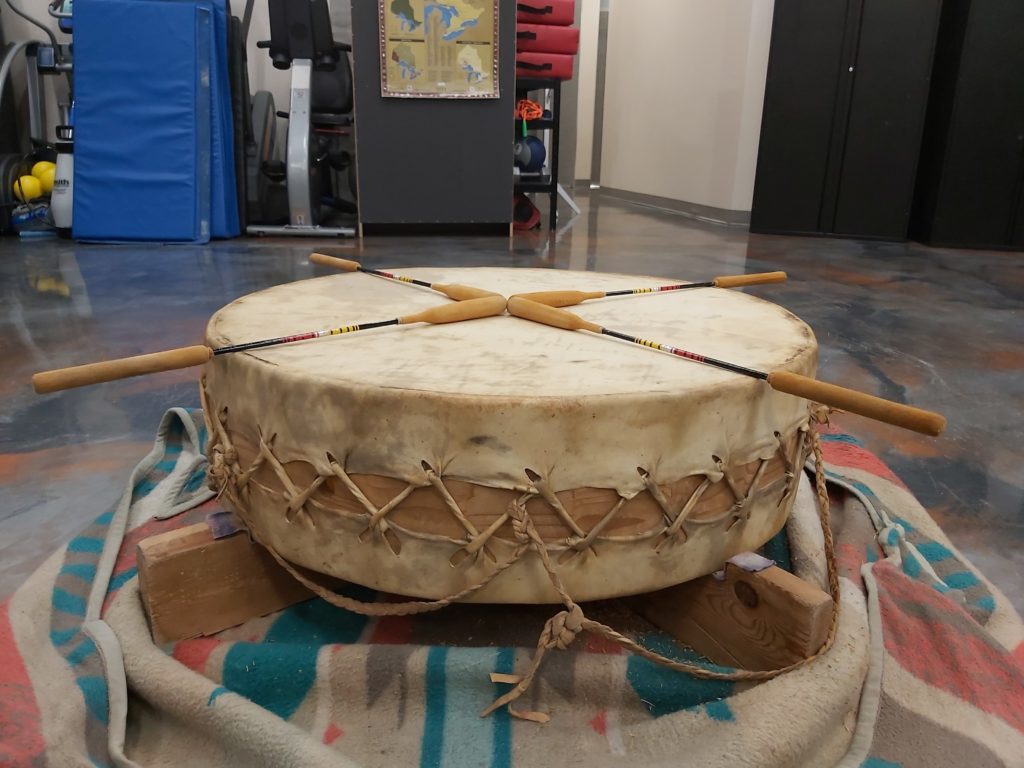

At the Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre in Windsor, Ontario, a traditional drum circle is practiced every Wednesday for Indigenous men and youth in the region. Each week, Indigenous men and youth burn tobacco over the drum and smudge sage in order to cleanse themselves of negativity. The program is called Kizhaay Anishinaabe Niin, which is Ojibway language for “I Am a Kind Man.”

The program helps “engage men to take action to end violence against Indigenous women.” It is offered through the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres and is a guided approach to healing “that recognizes the distinct histories, unique cultures and shared traumas of all Indigenous people negatively impacted by colonization.”

According to Brian Gray, the facilitator of the drum circle at the Can-Am Indian Friendship Centre, the drum is used to teach youth the Seven Grandfather Teachings, which of all Indigenous teachings in North America are most commonly used from coast to coast. The Seven Grandfather teachings are Dbaadendiziwin (humility), Aakwa’ode’ewin (bravery), Gwekwaadziwin (honesty), Nbwaakaawin (wisdom), Debwewin (truth), Mnaadendimowin (respect) and Zaagidwin (love).

“The thought behind it is to be a more preventitive measure against violence against women,” says Gray. “To instil these beliefs in our youth so we nip it at the bud.”

The program, says Gray, teaches youth values that they “might not be getting at home” because of intergenerational trauma that has been inflicted upon them by the residential school system.

Of residential school survivors, 69.9% cited loss of cultural identity as having nearly the same negative effect on them as did verbal and emotional abuse (70.7%).

“Our culture was stripped away and it’s kind of to bring more life back into the culture with the youth so that they are exposed to it and they will spark interest and curiosity and they can find guidance later on,” says Gray. “It’s for all Anishnaabe people just so that they can get in tune with themselves.” Anishinaabe is the name of culturally related Indigenous people located in Canada and the United States which includes the Odawa, Saulteaux, Ojibwe, Potowatomi, Oji-Cree and Algonquin peoples.

In a recent drumming at the Friendship Centre, men of all ages gathered around the drum. A nine-year-old boy who attends with his father appears to lead the group in song while boys and men aged up to 60 recite songs from the Ojibwe language. The drum is considered to hold the sacred spirit of the grandfather and helps foster a connection to spirituality, says Gray.

“I was told before that I used to be into the culture in my younger days,” says Gray. “Then I stopped for a little while and every time I heard the drums I’d get shivers up the base of my head. An Elder told me that this was the ancestors calling me back to the culture. It’s powerful, it’s very therapeutic.”

Similarly, Lamouche believes that Indigenous performance can be used as a wa y to create spiritual and mental well-being and provide a form of healing from intergenerational trauma.

“Now we are able to practice our culture and our spirituality but we also carry these wounds,” says Lamouche. “We have to take responsibility for our healing. We can recreate what that looks like for ourselves.”

This connection to her culture also means, for Lamouche, a connection to spirituality and safety.

“I find in the culture and the ceremony there is positive thinking and positive psychology,” she says. “Through ceremony we’re taught not to think negatively.”

“I find myself in safe places like powwows and community events where I can work in education,” says Lamouche, “But it shouldn’t have to be that way.”

Still, she says, when she walks outside or goes for a run by herself she fears for her safety. This is the reality for many Indigenous women in Canada. Lamouche thinks that the present moment is a time of recreation for Indigenous women.

“I think it’s happening more now,” she says. “We have more choices than we did during the time of colonization.”

This year, Lamouche was awarded the Leadership in Education Award from the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women.

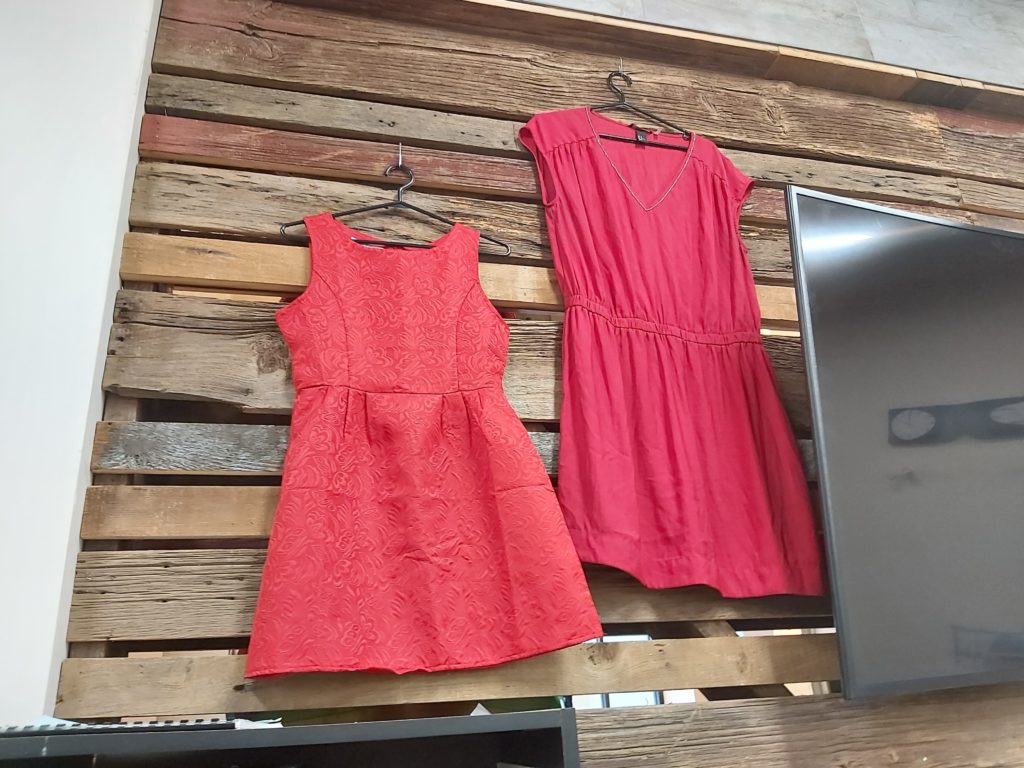

In its final calls for justice, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls challenged “all governments to ensure that all Indigenous women… are provided with safe, no-barrier, permanent, and meaningful access to their cultures and languages in order to restore, reclaim and revitalize their cultures and identities.”

It also calls for all governments to acknowledge, recognize, and protect the rights of Indigenous Peoples to their cultures and languages as inherent rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. This view echoes what was said at the outset of the Inquiry by the Elders, “stay grounded in culture, which represents the strength of Indigenous women and their communities.”