Japan is becoming more understanding to mixed-race people – aka hafu – due to their growing appearance in the media spotlight, though with returnees left out in the shadow.

When I say I’m a returnee, people say ‘No, you’re just Japanese’

says American-born Japanese Makoto Yanagita, who now lives and works in Tokyo Japan.

Makoto spent his formative years travelling the world. He was born in New York in the United States and moved to Canada at the age of two. He then moved to Japan for the first time at the age of three and spent about seven years in Hyogo prefecture.

Because of my Japanese appearance, Japanese people would just regard me as an ordinary Japanese, so I would often have to show my US passport to prove that I was born in the US, explains Makoto.

“People would then stare at me in a bit of surprise – it made me feel like my other half identity as an American was doubted and neglected.”

One of the difficulties he has experienced in Japan is when he struggled with the Japanese language.

Japanese is a very elaborate language that focuses on the social status frequently determined by the age and/or occupation of the person you are conversing with. Millions of different expressions are used in a very subtly way to convey different levels of respect.

However, it was not after he moved to Japan for the first time that he learnt about the complexity of the language influenced by the culture of such reverence.

“When I speak with people senior to me, I think I’m speaking stupidly”, explains Makoto, “Because I rarely had the opportunity to use Japanese growing up, except with my parents. So, I’m often considered kind of impolite by certain people.”

What kind of people are kikokushijos or returnees anyway?

According to a research by Kyoto Women’s University, that the term “kikokushijo” (which means returnees in English) was first coined by the Ministry of Education of Japan back in 1960s.

Kikokushijos are children who were born to Japanese parents either in or outside Japan and have spent more than one year abroad. With globalisation, their parents are mostly expatriates sent abroad requested from the headquarters in Japan.

In many cases, their children claim to have issues adapting to their native home country, which is often attributed to the fact that they are culturally not Japanese when their appearance suggests otherwise.

Some even experience barriers with the language because they somehow became more comfortable with the local language than with Japanese and they even used the local language to their parents at home.

By 1970s, under the concept of Nihonjinron– a theory/study of Japanese – that emphasises the uniqueness of the Japanese society, kikokushijos who were regarded as too westernised and individualistic had been characterised as problematic as they needed to be educated in (re-)adjusting to the Japanese society.

In 1980s, however, the public perception of kikokushijos gradually changed from something problematic to elite, due to their profound language and cultural skills gaining respect as indispensable means for the globalisation of the country.

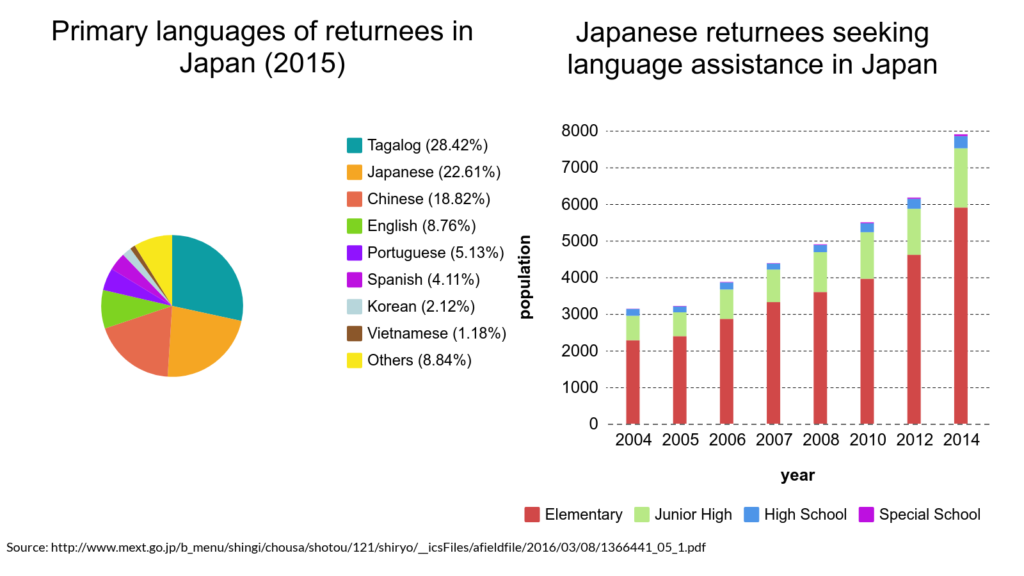

Time after time, nevertheless, kikokushijos are mistaken as fluent speakers of English although in reality many of them lived in non-English speaking countries.

By 2000, over 300 universities had begun to offer lenient admissions requirements for kikokushijos, which had been chastised as a sort of reverse discrimination against domestic applicants.

Personally, I went to an international high school in Tokyo where I met Makoto, and back then there was the word on the street that some parents would even venture to raise their children abroad and bring them back to Japan later, so they would qualify to apply for prestigious universities in the realm of kikokushijos.

Why were the parents so eager about it? Roger Goodman, professor of modern Japanese studies at Oxford University, says it is because a diploma from a prestigious university is like an entrance ticket into a prestigious company.

That being said, admissions criteria for kikokushijos vary from university to university, leaving the true definition of the term ‘kikokushijo’ slightly opaque.

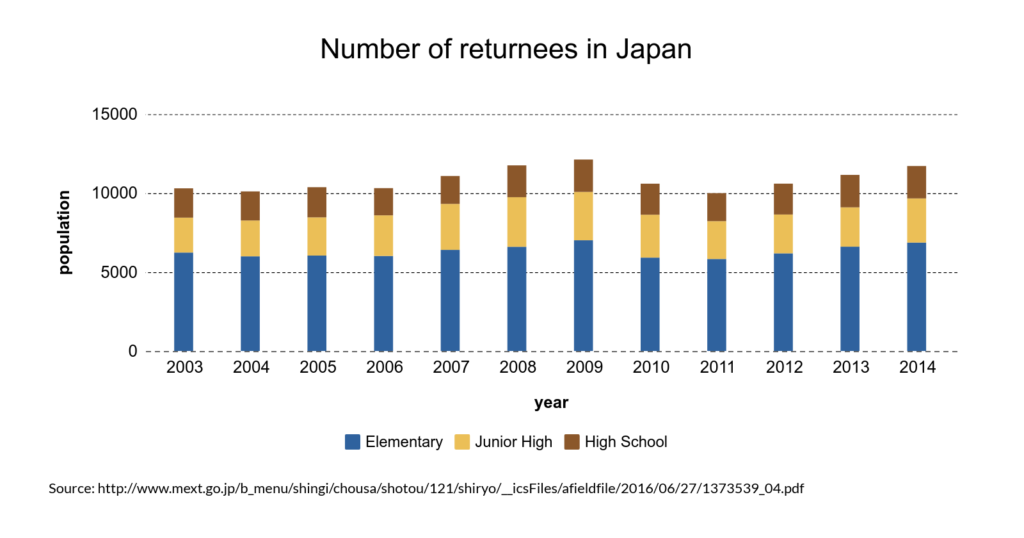

Nowadays, according to the Ministry of Education, the number of Japanese children who have spent more than one year abroad and returned to Japan reaches approximately 11,000 every year and the number would amount to as many as hundreds of thousands including those who are now grown-ups.

More than half a century has passed since the term came out, and yet some negative image of and neglect towards returnees in Japan still appears to linger on to some degree.

“For example, when you take a job interview the very first thing Japanese people check is your appearance. I am Japanese, ethnically, so I somehow pass the appearance check”, explains Makoto.

“But the minute I tell them that I’m a kikokushijoand so I speak English which is part of my identity, they just start assuming badly of me like I can’t mingle with other people because all kikokushijos are too self-assertive or something.”

This suggests that the language seems to be not the only obstacle that is perplexing the life of returnees in Japan. Makoto points out that it is something deeply embedded in the culture that defines your identity as Japanese.

So, what is identity?

According to a study by Stanford University, personal identity consists of a set of aspects or attributes of a person. These may be physical attributes, membership in social categories, person-specific beliefs, goals, desires, moral principles, or matters of personal style; all of which has to be something that the person is conscious of and which distinguish the person from some others.

In the case of Makoto, he is well aware that he was born to Japanese parents in which part of his personal identity lies as a Japanese, and yet he was born in New York and grew up being surrounded by people from a number of distinct backgrounds in Germany, whose very experience he cherishes today is what has formed his identity as a returnee.

Stanford University also explains that occasionally people speak of their personal identity as consisting of aspects of themselves that they feel powerless to change or which in their experience they cannot choose.

For better or for worse, Makoto himself did not have the choice to be born in New York as it was either a decision made by his parents or a consequence of a series of events that occurred naturally. This clearly sheds more light on the fact that this aspect of himself is incapable of being changed even by himself and let alone by others, as well as how his identity as a kikokushijohas been established organically.

While identity is spoken of searching for a sense of belonging in society in most cases, Stanford University points out that personal identity could also be conceived in terms that deliberately eschew group affiliations.

The reality is that there are a number of “silent kikokushijos” – people who do not reveal the fact that they are returnees usually in fear of standing out and consequently being the target of bullying.

In a country like Japan that regards conformity as a virtue and being “different” as eccentric or weird, standing out is the last thing you want to do. So, they would want to find a sense of belonging by trying to fit in rather than trying to be individualistic like in the west.

Makoto, on the other hand, turned his fear of standing out around (if he had any).

“Maybe they are scared of being isolated, but those who don’t come out as kikokushijos are probably more Japanese deep down inside because they choose to blend in as Japanese rather than being their true selves”, says Makoto.

Personally, I would rather be judged for who I really am than judged for who I’m not, and I think this is because I am a kikokushijo.

While a vast majority of returnees in Japan find it really difficult to fit in, some others including Makoto somehow manage to get by with their lives in Japan with minimum hassle.

So, how did he deal with issues of identity and belonging?

“To be honest, it would have been really, really difficult for me if it were not for friends who also come from similar backgrounds”, recalls Makoto.

“My experience at the international high school where I met you was quite enlightening in terms of learning about other kikokushijos in person. Like even in Japan, I was immersed in the environment where I had to use English together with Japanese all day every day, which helped maintain my language skills.”

Evidently, being surrounded by other kikokushijos helped him justify and solidify his own identity as a kikokushijo. In addition to this, he has also learnt at university how to adjust his mentality to the environment he is in.

“When I first came to Japan, I had some really difficult times because what was right and wrong in the countries that I grew up in was completely opposite here”, explains Makoto who describes the experience as having this “mental lid” on himself.

“But as I went on to university, I developed my mentality to be more adjustable through communication with a bunch of Japanese people with different values. Kind of like, when in Rome do as the Romans do, as they say.”

Will the identity crisis of kikokushijosin Japan ever end?

Returnee Japanese as well as mixed-race people, aka hafu, are similarly prone to cultural issues and struggles of identity and belonging.

However, it is true that they are becoming even more common so rapidly in Japan. With Japan’s positive attitude towards opening its doors even wider to the globalisation, there will likely be an increase in the number of Japanese workers being located overseas, meaning more returnees.

Nowadays, the Japanese society is relatively more respectful and understanding to these kikokushijos than in the past. Also, more and more educational institutions, including the high school Makoto and I attended, are putting more effort into meeting the needs of these returnee children, so they can better provide them with a good cultural foundation coming (back) to their native island.

Not to mention, not all kikokushijos get bullied just because of their unique backgrounds and upbringing. Just like Makoto, some settle down with not so major issues, make mates of life, and their life goes on.

To reiterate, the key is the proactive attitude towards trying to adjust yourself to the country or environment you are in – whether it be in Japan or elsewhere. If you do not speak the language, learn it. If you do not understand something, ask. If people think you are weird, explain.

Having said that, particular stereotypes and prejudices do remain, which can result in unnecessary rift between kikokushijos and the local Japanese, often leaving kikokushijos feeling alienated that can lead to even more serious issues for them.

As opposed to the image of kikokushijos as well as hafts in the media, they are ordinary people with Japanese roots – their uniquely distinct background and experiences cultivated abroad does not make them any less Japanese, but just more global-minded which is actually what Japan is urging the domestic Japanese youths to be.

Subject to pros and cons of being ‘different’ in one way or another, kikokushijos may be a quirky batch of people within the Japanese society. But aren’t kikokushijos, who are actually Japanese with a good understanding of foreign culture with good language skills, new pioneers that can pave the way for a new global Japan?

“Japanese policymakers should be located abroad”, suggests Makoto, “Only to return and experience reverse culture shocks in Japan.”

Japan is all about black and white, but kikokushijos and hafus are minorities that come from the in-between. If Japan begins to see and accept this grey zone just the way it is, then the country may be just a few steps closer to true diversification.