Their grandparents spoke Manx, their children speak Manx, they don’t. When a language skips a generation, children become the gatekeepers of a language and its culture – how does that impact the language’s growth among adults, especially parents?

The schoolyard is full of kids laughing and playing, rubber balls bouncing and hula hoops circling. From all external appearances, it is a regular school recess break in the small city of St Johns on the Isle of Man. The old stone building matches the exterior of St John’s Chapel across the road, next to the site of Tynwald Hill, where the Vikings who settled the island originally organised the government of the island.

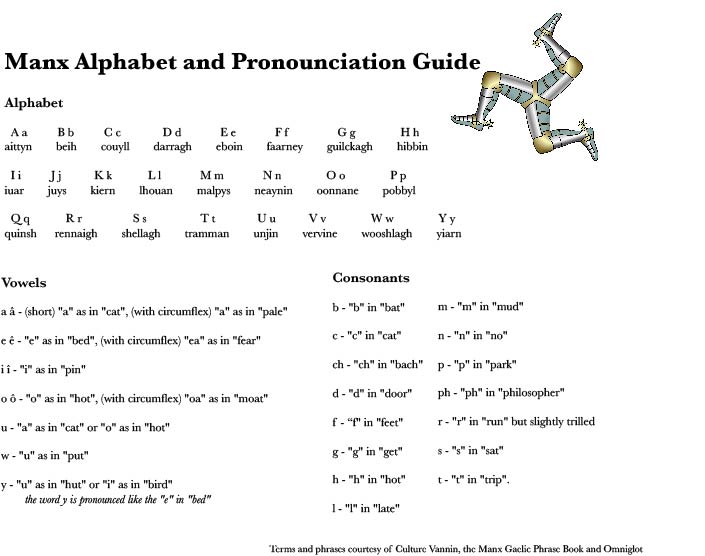

The sign on the gate reads Bunscoill Ghaelgagh, which translates to the School for Manx. The teachers called the children in, not in English, but in Manx Gaelic, the native language of the Isle of Man. Classroom walls are still decorated with “ABC’s” and pieces of the children’s work, but instead of learning how to write ‘apple’ and ‘dog’, the first form is learning ooyl and moddey .

“It is important that my child learns to respect and learn about the local culture and tradition,” says Mari Smith, whose child currently attends the Bunscoill. Like most other parents, Smith began to learn Manx as an adult – many parents begin at the same time as their children do, which raises a number of complications.

“I think I probably progressed in parallel,” says Aalin Clague, who sent her children to the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh. “So I, um I thought I was better than I was, so when I saw the reading books and realized I didn’t understand everything that was going, it was a shock to me.”

Clague, who also directs the Manx-medium band Clash Vooar, had been studying Manx on and off until her children started attending the school. Like all parents, Clague wanted to assist her children with their schoolwork, but often she – as well as other parents who send their children to the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh – found herself learning the language at the same pace as the children.

Since many of the parents are learning Manx along with their children, their ability to support them with schoolwork is somewhat limited. Some have grandparents who can help, but thanks to the sentiments of many around the end of the 20th century, many don’t even have that. Changing views and perspectives on the language is one thing, but patching up the gaps where the language is missing is something else entirely.

“At the moment there’s a lot of great stuff for beginners up to about intermediate level but there’s not a whole lot after that to help learners get fluent,” says Jamys O’Meara, who served as the interim Yn Greinneyder, Manx Language Development Officer, during the summer of 2019. During his tenure as the Yn Greinneyder, O’Meara was working to help develop intermediate materials for Manx learners.

“It would be nice to have the English translations of [class] books as I often don’t quite understand the story due to my limited Manx,” said Smith, citing one of the challenges she as a parent felt trying to assist her children. Other parents indicated similar areas of need when it came to materials geared toward the Manx-learning adult.

Manx-medium education

The primary school is the first of its kind on the Isle of Man, and currently has 65 students enrolled across four classes. Since the school began with nine students in 2001, it has increased in popularity and prestige across the island.

“We started off as a unit inside the school and Douglas for a short while, then a unit inside the new school at St John’s until such time as the old school was ready,” says Phil Gawne, director of Mooinjer Veggey, which translates to “the little people”, and one of the founders of the Bunscoill. Mooinjer Veggey is a charity that supports Manx education for pre-school aged children.

Gawne raised his children in Manx, but was one of the few families on the Island that did so at the time. When he learned that other parents that were interested in having their children learn Manx in the classroom, he worked with several other individuals to help establish an institution for Manx education.

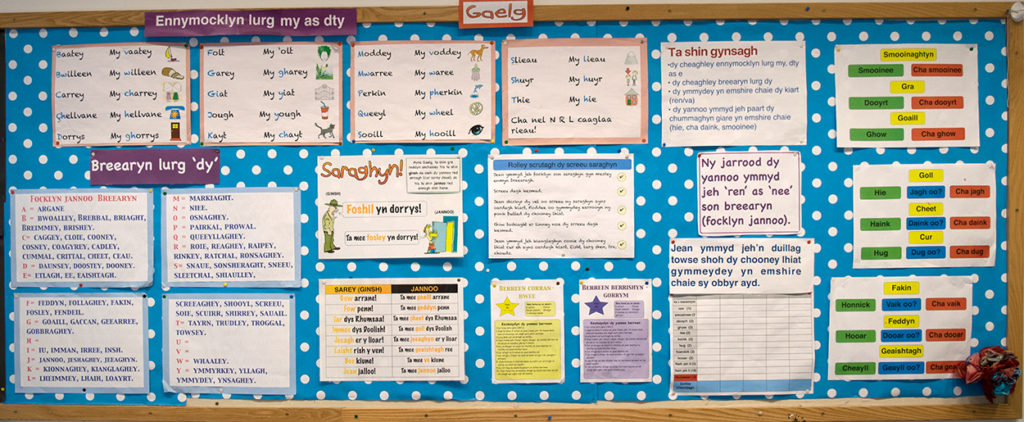

A bulletin board in the Form 1 class promoting healthy activities. This board has various yoga poses with the correlating Manx word.

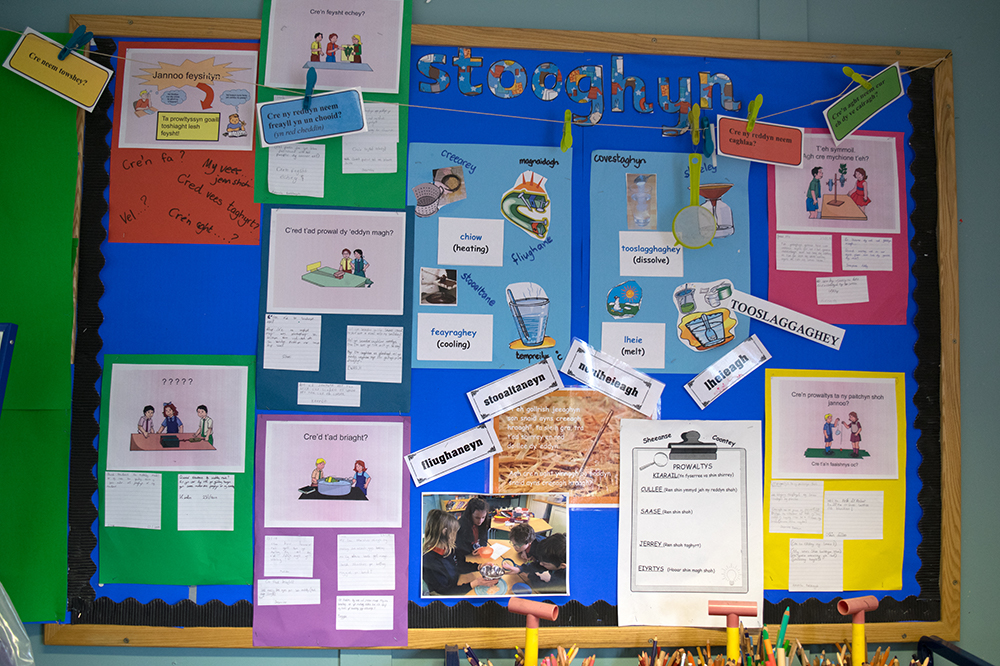

In the Form 3 class, students are working on common terms for cooking or baking

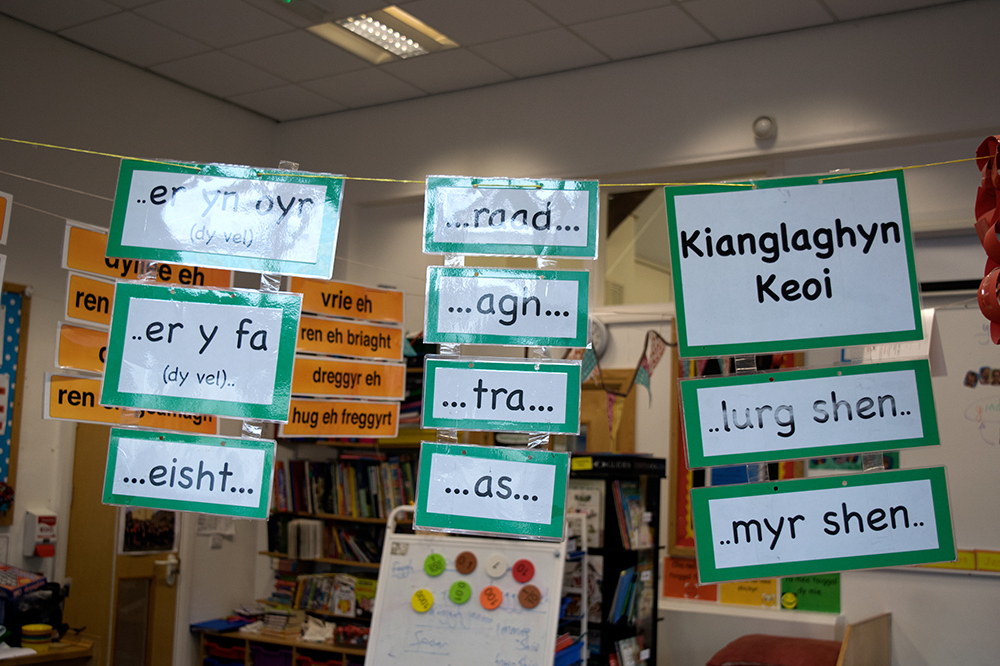

Bulletin boards provide reminders for students for everything from vocabulary to grammatical conjugations

The rooms of the Bunscoill are decorated with lots of colours and strung up vocabulary words as visual aids for learning the language.

Students in Form 4 (the upper level class at the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh) work on an essay assignment in Manx.

“It’s inspired by the feel of most things because it was a relatively new thing and obviously a successful thing,” says Gawne. “We could see immediately when we started this is this is really going to work, the kids were speaking in Manx.”

From a couple of hours of Manx language classes a week to full-time education, the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh has become a model institution on the Isle of Man for Manx education. The students speak and learn in Manx, and by the time they finish at the Bunscoill, most are fluent Manx speakers.

My mom can speak, my sons can speak, so there’s the language gap.

Aalin Clague

The children may be speaking Manx at school, but at home? Many of the children come from families where the parents, though born and raised on the Isle of Man, do not have the language, as a result of years of language suppression, favouring English over local dialects. In the 70s and 80s, many Manx revitalisation efforts met with extreme opposition, not from the government, but from an older generation of Manx people.

“It would be felt that it wasn’t a proper language because it wasn’t to them,” says Gawne. “It was the language of poverty. It was a language of the past…[a waste of] our time, spending thousands, a couple of thousands of pounds on this decaying dead language. And there was a very strong and really strong anti-Manx feel from a certain part of that generation of older Manx people.”

This shared sentiment proved so successful in suppressing Manx Gaelic that the number of language-users dwindled to the point that UNESCO declared the language extinct in 2009. Most of the parents of the students at the Bunscoill grew up in an environment where English was the preferred language, and if they learned another language, it would be French or Spanish, not Manx.

“I definitely think if I weren’t living in the Isle of Man, it probably wouldn’t be important to learn Manx…in the same way that it’s not too important for me to learn Haitian Creole,” says Owan Williams, who attended the Busncoil as a child and now attends an English-medium secondary school in Douglas.

However, the impact of the UNESCO designation in 2009 did not lessen the power of the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh and the people involved. The Bunscoill had been established in St John’s for six years by then, and the classes continued to grow.

The same year UNESCO declared the language extinct, the efforts of schoolchildren at Bunscoill Ghaelgegh helped it to be reclassified as critically endangered.

“I couldn’t have known was that our children would then write to UNESCO at a later stage and say to UNESCO, What are you doing here? How can our language be extinct?” says Gawne. The same year UNESCO declared the language extinct, they reversed their designation and reclassified the language as ‘critically endangered’ – the first time UNSECO had made such a decision.

True, many parents didn’t speak the language, what Manx was left in government was mostly for ceremonial reasons, but the students of the Bunscoill Ghaelgagh were becoming the standard-bearers of a refreshed Manx language attempt.

“Revitalisation has appeared because of our efforts,” says Julie Matthews, the headteacher of the Bunscoill. Matthews, along with the other staff members, all speak Manx fluently and use it whenever they interact with both students and teachers. However, there are still those who see the school as unnecessary or a waste of time and money.

“Our son reads English fluently and is excellent at maths and science – there are no drawbacks academically. Socially, a school’s a school, and so the language is irrelevant,” says Cori Franklin, whose child currently attends the Bunscoill. “The only ‘challenge’ is with parents/friends of other schools not getting the Bunscoill and so our having to repeatedly justify and explain it.”

Franklin is not alone in the struggle to justify her family’s choice of school. When Gawne began his push to create the Bunscoill, he had to repeatedly make the argument for Manx language education to what he calls the “old Manx people,” those who grew up as part of a generation that generally condoned the Manx language and culture in favour of English.

“In the late 90s, there was still a very prevalent view that this was a complete waste of time and money,” says Gawne. “So you had to argue your case not on sort of heritage and culture, warm, touchy-feely stuff. You had to have hard facts.

“So the hard facts were, we set up a bilingual playschool and a lovely primary school because bilingual children outperform their monolingual counterparts in practically every everything they do. This is a fact.”

Mrs Molyneux, who has two children currently attending the Bunscoill, did not speak Manx before enrolling her eldest, but since then has been taking advantage of morning classes offered at the café down the street, organised by Culture Vannin, the Manx Language foundation charity.

“When I first heard about the kind of tailored lessons that Culture Vannin were providing for small groups of parents, I thought Christ, why waste money, that’s all that money just for a few people,” says Clague. “But actually that’s the way it works. And I think when people are getting something out of it socially that pushes them on to continue.”

Clague, her husband and many other parents are able to take advantage of the classes and can share the same support that their children have in the classroom.

“Previous to the Bunscoill, I knew nothing of Manx language or culture and didn’t feel ‘Manx’ or connected to the Island despite having lived here since I was 11,” says Molyneux. When looking for schools, the Bunscoill stood out to her as an opportunity to give her children a sense of belonging and grounding to the Island, as well as connecting them to the Manx identity.

“We choose the Bunscoill to support our child, and more importantly to normalise it for them. To help normalise the language of other learners, now and in the future,” says Franklin. Franklin and her husband have both learned to speak Manx with fluency after they became adults, continuing their study side-by-side with their child.

Since many of the parents are learning Manx along with their children, their ability to support them with schoolwork is somewhat limited. Some have grandparents who can help, but thanks to the sentiments of many around the end of the 20th century, many don’t even have that. Changing views and perspectives on the language is one thing, but patching up the gaps where the language was missing is another beast.

Most children finish the Bunscoill as native Manx speakers, but when it then comes to continuing to speak the language, especially if it’s not spoken at home, they will often lose much of the language. Williams finds opportunities to speak Manx at home with his family and at Scran music rehearsals, but when it comes to speaking the language at school, that’s a bit of a different matter.

“I don’t have many friends my age who can speak Manx, unfortunately. Well, I do, but not in school,” says Williams. “But, one of the members of Scran…is a year below me in school, so we don’t speak English to each other, we just speak Manx.” Groups like the youth bands Scran and Bree offer young people the chance to continue speaking Manx in a day-to-day setting, increasing the visibility of the language.

“With some hard work and time it would be nice to see the language make a ‘come back’ within modern-day Manx daily life,” says Smith. “I strongly believe in the more languages, the better for individuals.”