2019 marks the thirtieth anniversary of German re-unification. Explore the old East-West border by following the roads and towns that weave through it.

‘Here, Germany and Europe were divided until 10 December, 1989, at 11:00am.’

The sign flashes quickly by as we speed along the road, the only give away that we are crossing through the former Iron Curtain.

These markers appear frequently in this part of the world, as the frontier between old East and West snakes quietly through the landscape – across roads and between neighbouring villages.

“Wait, are we in the East or West now?” I ask my boyfriend, our driver and a native of the region on the edge of the old border.

It’s often remarked that an inner, i.e. psychological and cultural, border remains.

Dr Nick Hodgin, cultural historian

At this point, we are in fact driving eastward across the former ‘Inner German border’ as part of our journey through the Harz National Park, a mountain range that was once at the heart of Cold War tensions.

I’m already well acquainted with the area around this part of Germany, but I was keen to get deeper under its skin while I was visiting the country for Easter. So, we decided we were going to embark on a road trip through and around the mountains, aiming to hit as many spots on the historic ‘Fachwerkstrasse’ (or ‘Timber Framed Road) as possible, both East and West, over four days.

East is east, and west is west?

Despite the physical frontier being long gone, in the current climate of 2019, old tensions between East and West can still rear their ugly head.

According to cultural historian Dr Nick Hodgin, “It’s often remarked that an inner, i.e. psychological, and cultural, border remains.”

This metaphysical border manifests itself most clearly through election results and the differing general attitudes to issues such as freedom of movement and how the past is remembered.

“For those unsettled by adverse society (as a result of immigration, the refugee crisis, etc.), the GDR is remembered as a state and a time when this seemed not to be an issue,” explains Hodgin.

It is an interesting phenomenon given that, as you travel through the old border region, it can be almost impossible to tell there was ever a divide at all.

Day 1: Quedlinburg

As we arrive in Quedlinburg I think to myself, “Ah, this is what Disneyland was trying to achieve with its look.”

The rows of slanted, timber-framed houses must be seen to be believed, and I can’t help but wonder why this truly unique place, the entirety of which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, doesn’t attract more interest from British tourists.

I’m also struck by how beautifully preserved the mediaeval houses are, something which later research leads me to learn is due to the good fortune of history.

The town, although unscathed by the Second World War, fell into a dilapidated state in the last century as the GDR could not afford the much-needed restorations. When Germany reunified in 1990, this meant the entire town benefited from state of the art restoration work.

It is also fortunate that areas in former East Germany benefit from the controversial Solidarity Tax, something which West Germans are still largely unsure about. The tax is applied to citizens across the whole of Germany but used to cover the costs of re-unification, primarily in the East. As a result of these tensions, it is geared to become one of the major points of contention in the next set of federal elections.

Day 2: Wernigerode to Duderstadt

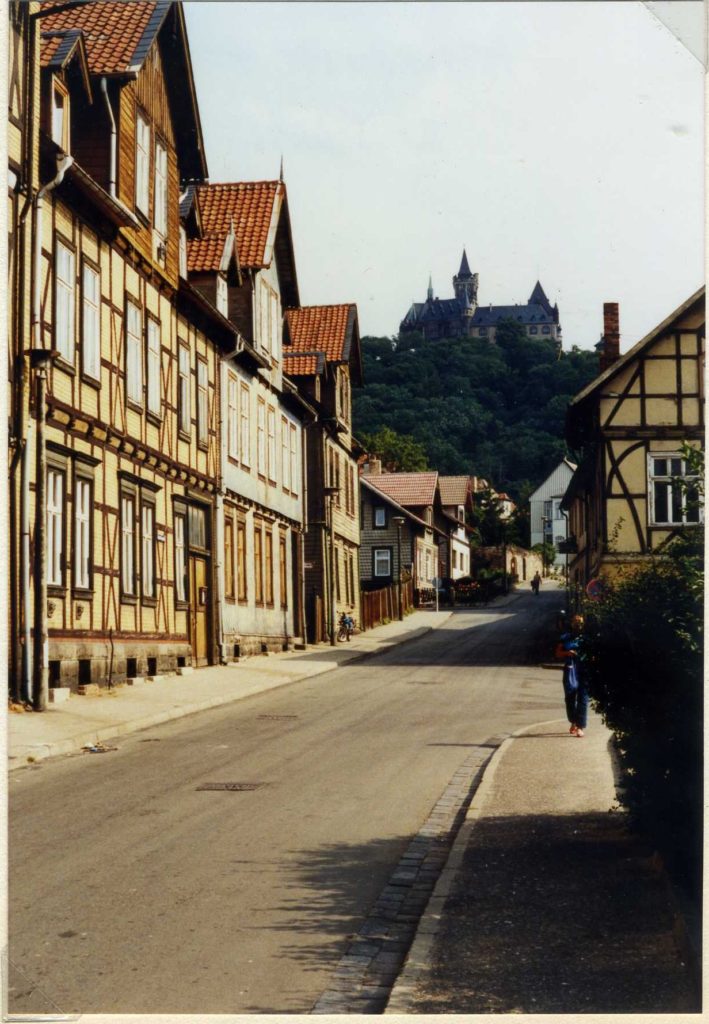

Our second stop, Wernigerode, is a short hop along the autobahn from Quedlinburg. It is more obvious now that we are in the foothills of the Harz – the tumbledown town sits below an imposing rocky hill, upon which its gothic revival castle looms overhead.

We reach its central square and I’m struck by its absurdly pretty town hall, before going off to explore the maze of streets and flower-lined squares for a few hours, finishing in Café Wien for cake and coffee.

Wernigerode, 1988

(Image: SludgeG, Flickr)

Wernigerode, 2019

Honestly, when I see the old border, it makes me realise how fragile our freedom of movement is.

From Wernigerode we make our way to Duderstadt, straight through the densely forested Harz National Park. Out of the window I catch flashes of GDR-era tower blocks, perched awkwardly on the hillsides of these otherwise wooden-clad outposts.

It’s a beautiful but eerie landscape, and the bright April sunshine has been lost among the trees. When I suddenly notice that the ugly, concrete towers seem few and far between, I ask my driving boyfriend why.

“We’ve already crossed the border back into Lower Saxony,” he answers. Apparently there were signs informing us about this development, but I missed them. Easy enough to do around here.

This corner of Lower Saxony, a state in the former West, borders the old East on two sides; with the federal states of Saxony to the East, and Thuringia to the South. The odd bit of Soviet architecture aside, it’s almost impossible to tell which side of the border you’re on unless you know.

We make our way out of the forests and soon enter Duderstadt, the third name on our list. It feels much smaller than our other ports of call, but is a lovely spot to catch your breath, take in the history, and find your nearest Eiscafé.

Day 3: Duderstadt to Hann. Münden

The next day, before heading to Hann Münden, we take a quick detour eastward and stop on the edge of Thuringia. Here you can actually walk a length of the old border wall between East and West, preserved as part of the Grenzlandmuseum Eichsfeld.

Wandering along its length, I am struck with how strange it must be to live in the shadow of these border fortifications, the most infamous in recent European history. I ask my boyfriend about it.

“Honestly, when I see the old border, it makes me realise how fragile our current freedom of movement is,” he answers, eyes fixed on the former watch tower in front of us.

It’s a fitting answer to my question, considering that immigration is such a hot topic in Germany at the moment; an issue often at the heart of GDR nostalgia .

Driving away, and heading off the autobahn for Hann Münden, is like stepping back a century in time. I find this a comforting thought after being surrounded by Cold War steel and concrete for the past couple of hours.

The town sits atop of an island between two rivers, its cute pastel coloured houses crumbling slightly around the edges. I quietly think to myself that it’s the most beautiful stop on our trip.

However, like its neighbour Duderstadt, Hann Münden saw difficult times in the nineties, after German reunification. The whole western border area faced some of the highest rates of unemployment in the country, whilst not benefiting from the Solidarity Tax like their eastern counterparts, including Quedlinburg and Wernigerode.

Today, however, it’s bustling with visitors to the old town. We end the day with a pint of the local brew – Dr Eisenbart Bier (named after one of the town’s most famous former residents, apparently) – in Hann Münden’s Ratskeller.

Goslar

We reach Goslar in just over an hour from Hann Münden, taking advantage of the autobahn the entire way. The town, a warren of timber-framed houses overlooked by the forested peaks of the Harz, is another UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Its architecture is particularly fascinating, even by the standards of our trip. Its crooked fachwerk houses commonly feature slate cladding, which gives them an ethereal black glow.

“It’s very Brothers Grimm, isn’t it?” I remark. It’s easier to imagine witches swooping through the air here for example than, say, twee little Quedlinburg.

We make a stop in Goslar’s brewery, to sample the local beer and ‘bieramisu’ (yes, that is tiramisu made with beer) before the boyfriend comes out with one last piece of wisdom for the trip.

“Going back to earlier, I think people have forgotten how awful the divide between East and West was. It’s too easy for people who haven’t experienced the past to misremember it.”

Thinking of this remark now, I am reminded of something the historian Marion Loeffler said to me.

“Concentration on the political history of both sides of the wall… and on the great incisive events, has resulted in the imagination of identities, which were not always there,” says Loeffler, who grew up in the GDR but now lectures at Cardiff University.

With the current political turmoil in Europe, it’s good to be reminded that history is a crucial tool at our disposal, but that we must be careful not to slip into nostalgia.

As I sit in Goslar, whose streets have remain unchanged for a millennium despite surviving two world wars and the Iron Curtain, I can’t help but think that Germany is the best place of all to learn this lesson.