The use of food banks continues to rise in the UK, but what was once a last resort for the homeless or unemployed now supports an increasing number of working families relying on charity to feed their children.

From the window she sees him, stepping out the car and up the garden path. “Pizza’s here!” the mother shouts from the top of the stairs. Two small children rush hurriedly past her, almost bundling her over in excitement.

It’s the weekend takeaway scene played out in hundreds of homes up and down the country, but here something is different.

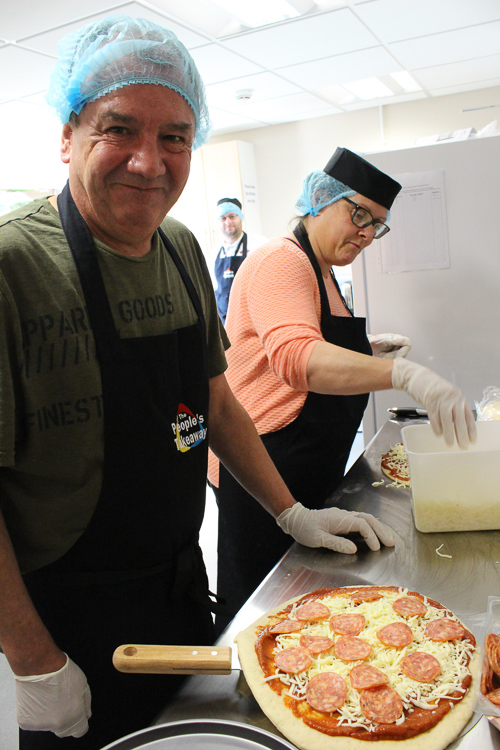

The young woman doesn’t hand over any money as the box is passed through the doorway. No card is swiped, or tip offered. She just says, “Thank you” as the delivery man smiles and heads off into the night. The reason for this is because the pizza is part of an innovative charity project, The People’s Takeaway, operated by the East Durham Trust (EDT).

As the kids tuck into the hot food, their Mother watches on, enjoying the delight on their faces. As a parent, it’s a feeling in life that money can’t buy. Nevertheless, she is grateful that neither of them knows why the pizza is free.

A fifth of the UK population now live in poverty. This includes over four million children, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the DWP (Department for Work & Pensions). In this growing section of the population, many people need to rely on charity just so they can eat, with both short and long-term implications for their health, wellbeing, and integration into society.

“When you talk about social inclusion, when its families the children will come to the door and chat away, over the moon to see this pizza,” says Donna a volunteer at the EDT. “It comes in a normal pizza box with a proper bag like a delivery person would have so they don’t know any different. They can go to school on Monday and say oh we had pizza on the weekend.”

The People’s Takeaway project was originally put in place to provide a hot meal to families who could not afford gas and electric to cook. Now the service is also offered to families who have received a food parcel during the week, and acts as a weekend treat for children to enjoy, without them having to know where it came from.

The growth of people turning to charities to feed themselves can be seen nationally by the rise in the number of three-day emergency food parcels handed out.

The Trussell Trust reported that in the last year its food banks had given out 19% more than the previous year, following a 13% rise the year before.

In the same year, the East Durham Trust saw an increase from 30-40 parcels a week to 100-120. An increase of 200%. One week they gave out 200 parcels.

The EDT doesn’t operate in the traditional food bank model. Food parcels are often anonymised and delivered, sometimes to homes or to smaller outreach centres in the surrounding villages.

Protecting the dignity of the people they support is a consistent theme throughout all of their food projects as the negative stigma of turning to charity can prevent individuals from asking for help.

“We found out very early on that certain people wouldn’t dream of putting themselves forward,” says Chief Executive Malcolm Fallow. “If you look at each individual case study that gets a food parcel, one of the things you’ll discover is that they should have asked for a food parcel usually about two days before they actually did.

“Even GP’s send people to us, because people will present to a GP with health issues but they’re not really health issues, they’re social issues.

“We’ve had a food parcel referral from a doctor who said, ‘There’s a guy in here who’s come in complaining about stomach pains. Can we give him a food parcel please? Because the only thing wrong with him is that he hasn’t eaten for five days. He’s fed his family, but he hasn’t fed himself.”

Due to this, Malcolm says thoughtful initiatives like the People’s Takeaway, or events in school holidays that provide food in the absence of free school meals, have been sensitive ways to help those struggling in the community.

“It’s about making sure the families feel valued, and it’s not just the handout mentality that probably food banks are labelled with,” he explains.

In other cases, the need for support may be so severe that a person must come forward.

For one former client, Dan, receiving a food parcel was a huge relief in a difficult period of his life.

“It was desperation really,” he says. “If she’s got no shame giving me it, I’ve got no shame going to a food bank.

“It’s a good job it’s here. There’s a lot of charities if we didn’t have in this country we’d be knackered. Charities and the folk that run this, if it wasn’t for them, I bet there’d be thousands of bloody people jumping off viaducts. If we didn’t have food banks what would we do?”

After relying on the trust himself, Dan felt compelled to volunteer, and now cooks pizzas in The People’s Takeaway as a way to give something back to those who supported him.

“That’s what I do it for, because they helped me so I can help pay it back,” he says. “For my dignity, I thought they went out of their way to help me, so I paid it back. Its only right that isn’t it.”

Volunteers are an essential part of the EDT, but for Malcolm, the importance of their involvement is also that it brings them back into a community where the pressures of poverty can often leave them isolated.

“Nothing excludes people like poverty,” he explains. “It forces people into their back bedrooms, it forces people into their homes.

“Volunteering is good for your mental health.”

It’s a thought echoed by Leaona Clarkson on the front desk, who sees first-hand how this relationship at the core of the institution is beneficial to both sides.

“Working down here, we couldn’t run the place without the volunteers,” she says. “But at the same time, I’d like to think that they are getting more out of it than we are.”

People in the former mining villages of East Durham are used to helping each other. Since the introduction of austerity measures, the North East of England has had half a billion pounds less to spend every year.

County Durham is among the worst affected areas in the country, with its funding cut by 31% between 2010 and 2017, according to research from Cambridge University.

However, in the era of austerity, postindustrial communities such as East Durham have also had to survive the poor employment opportunities available in the area.

According to research by the Living Wage Foundation, five million workers in Britain are in low-paid and insecure work. The highest rates of this are experienced in the North East, Wales, and the West Midlands.

This problem of underemployment is most commonly represented by the no obligation of zero hours contracts, or the precarious gig economy which now employs one in ten working age adults in the UK, or 4.7 million people according to the TUC and the University of Hertfordshire.

This increase in employment instability leads more people to turn to charity. At the EDT Helen Waller, who runs the SPIED initiative (Stop Poverty in East Durham), has noticed that those who need support are coming from more diverse backgrounds.

“We have teachers, all walks of life,” Helen says, as she explains the hunger and desperation of some of the people who come to the trust. “We have people eating rice puddings straight out the tins.”

A consequence of underemployment is how working families can fall in and out of poverty as they experience multiple short-term periods when they are in-work. This is often obscured by record employment figures touted by the government, but as Malcolm explains, it is a common feature of in-work poverty.

“When we’re talking about the gig economy,” says Malcolm. “People get food parcels then they’re alright for a few months and then they get food parcels again. That’s the world they’re in. It’s not as simple as somebody falls on hard times gets a food parcel, sorts themselves out and you never see them again. It doesn’t work like that.”

Credit – S.Poole

Experiences of in-work poverty have been made longer, and more severe by the introduction of universal credit, as the standard waiting period can be up to five weeks before claimants receive their first payment.

“Universal credit was rolled out a year and a half ago,” says Malcolm. “And it had a big impact.”

Malcolm points out that the more disadvantaged people are, the more they will be affected by universal credit. He explains that the advice the DWP gives to people who have their benefits stopped, reduced or delayed, simply does not work for areas that are as deprived as those in East Durham.

“One of the things they teach the staff in the DWP to say is to rely on, friends, savings and food banks,” he says. “Here people haven’t got savings.”

The government department is not only sending people on benefits to food banks ran by charities, but according to Helen, they send people directly to her for help, as if she was part of the same public services.

“If you ring universal credit up, they’ll say go to the food bank, that is their answer,” she says. “Apparently, universal credit call centre has my name and even says go see Helen at East Durham Trust. I’ve had people ring me from all over – universal credits told us to contact you.”

The EDT is an independent community centre, which operates thanks to funding from donations and National Lottery Funded projects. Like many similar organisations in other areas of the UK, it provides a vital safety net to the people in East Durham, who have nowhere else to turn.

Ten years ago, its main focus was supporting local community groups such as amateur football teams or fishing clubs but the needs of people in the area have forced them to evolve, according to Deputy Manager Lindsey Wood.

“When I first started that was the lion’s share of our work,” she says. “Over the years we’ve adapted. We’ve got more staff than we ever have had before, but it is more project based and poverty intervention.

“We didn’t have those when I very first started.”

While crisis intervention work is essential in helping people in deprived parts of the UK, it does not prevent families slipping into poverty. Referencing Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Lindsey explains that missing out on necessities such as food can have long-term effects on a person’s life.

“You can’t get a job if you’ve got no food and you’ve got no shelter,” she says. “It’s all a stepped approach, you’ve got to deal with the very basics before you can move up.”

According to the DWP, 30% of children in the UK live in poverty, with 70% of those coming from working families. The experience of social exclusion, in which people cannot fully access the opportunities and resources available to the rest of society, can damage these children’s future chances and limit their potential.

Studies from the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) show that children who have lived in persistent poverty during their first seven years have cognitive development scores on average 20% below those of children who have never experienced poverty.

This is a factor as children progress through school, as CPAG revealed in 2015, that 33% of children receiving free school meals obtained five or more good GCSEs, compared with 61% of other children.

In the long term, boys from the most deprived areas can expect to live 19 fewer years of their lives in good health, than boys in the least deprived areas. Girls are expected to live 20 years fewer.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission has forecast that by 2022, 1.5 million more children will fall into poverty, increasing the rate of child poverty to 41%.

If this prediction is accurate, such an increase in child poverty will have huge repercussions on the integration of a large part of the population and in turn the potential of UK society as a whole.

As the government faces the possibility of a no deal Brexit, there are uncertain times ahead both politically and economically. The former chancellor Philip Hammond has said leaving the EU without a deal may cost the British economy £90 billion, which could cause further damage to deprived areas of northern England, and the charities that support them.

The Institute for Public Policy Research North think tank (IPPR North) has shown that since 2009-10 there has been an overall £3.6bn a year reduction in public spending in the north of England, whereas the south-east and south-west saw a £4.7bn rise.

For Malcolm, any short-term changes to the political landscape are unlikely to change the reality of severe poverty in areas such as East Durham, or how much support they need from charity organisations.

“The best we can hope for really is that Brexit is just a muddled period of time,” he says. “It’s not going to change anytime soon politically, there’s going to be no U-turns anywhere, and even if there is, poverty is so deeply entrenched.

“It took 25 years since the pits shut in some cases to take some of these places to fall into that level, so to get them back is not going to happen overnight. There’s a generation lost.

“I wish we weren’t as needed as we are. It’s a frightening thought if we had to pull the plug out of any of the projects in here now, and where that would leave people in the community.”