It is now common knowledge that we are in a critical period to fight climate change; according to scientists, it’s do or die: we have 12 years to reduce global warming. But how much of a difference can we actually make, without first considering how we got here?

If you look at a satellite image of the earth, you can see how the green areas have gradually shrunk over the last twenty years; how oil has blackened the oceans; how whole islands- and whole cultures- are eroded as they become submerged by rising sea levels.

This, is what Rabab Ghazoul unapologetically calls the “scars of imperial exploitation.”

It is a damp and windy morning in August when I meet Rabab for an interview. As I wait for her outside the Wyndham Street Diner in Riverside, Cardiff, just off the city centre, I try the door and find it locked, and shelter from the rain under a tree growing out of the small area of paving around the entrance.

“Sorry, sorry!” she calls, speeding around the corner on her bike ten minutes later, the tails of her coat and her wavy, lightened hair flying out behind her. She hands me her bags as she unlocks the door, and once inside she turns on a lamp and swiftly darts to the kitchen to put on the kettle.

Rabab is originally from Mosul, Iraq, and first moved to the UK aged ten when her father came to study in England. In 2004 she co-founded the Gentle/Radical Film Club, and the Wyndham Street Diner has recently become their hub for grassroots, community-based work, centred in the heart of the Riverside community.

They call the centre ‘Al Mish’aal’- an Arabic concept which Rabab describes as ‘a fire you keep burning so travellers can find their way to their destination’ – a metaphor for what the centre strives to be for the surrounding community.

Inside, the room is warmly lit, with freshly-painted white walls and simple pine furniture. The view from four rectangular windows looks out to a brief ellipsis of green, before merging into a bending terrace of houses, with the mosque on the corner.

There are several desks that can be used for a small monthly fee (but are free for asylum seekers), bookshelves housing a small library of books on politics and art, and most noticeably there are plants everywhere that have been donated by members and friends – I count fifty-two in total. Rabab tells me the plants are an important part of the space – they are subtle reminders of life and growth.

Gentle/Radical isn’t an environmental organisation; nor an anti-austerity or anti-racism organisation; rather it is all of these things. It is a “platform for radical thinking, creative practice and social change” according to their social media pages.

Whereas arts and cultural organisations have a tendency to “diversify” their organisation from the outside after realising they lack members of black and ethnic minority backgrounds, Rabab says Gentle/Radical strives to turn this model “on its head.”

Their new space – the cost of which was largely crowd-funded – is situated in a part of Cardiff that is lacking in pubs, cafés, and other places where people might come together and talk about political issues like the climate crisis.

Just down the road from Al Mish’aal is a centre used by Riverside’s Bangladeshi community – who account for 6.4% of its population but only 1.4% of Cardiff’s total population.

Rabab points out that the people in this area are no strangers to the impacts of climate change – many have relatives back home who have been displaced by extreme weather and rising sea levels, and some are even climate refugees themselves.

The Environmental Justice Foundation predicts that by 2050, one in every seven people in Bangladesh will be displaced as a result of climate change.

Climate change is a word on everybody’s lips at the moment, but left out of the mainstream conversation are the many debates surrounding not only how we fight climate change, but who is fighting it and who suffers the most from the impacts, despite that many environmental justice groups are continually making these points, and have been doing so for years – long before Greta Thunberg and Extinction Rebellion came into the picture.

Reading Razmig Keucheyan’s Nature is a Battlefield, I was interested in perception of environment, which is now frequently foregrounded with “the” – the environment – usually equating it with the natural world – something often seen as virgin and abstract, and ruined or dominated by human existence.

Rabab places two grey mugs down on the table. How does she define environment? I ask.

She pauses and takes off her glasses; leaning back and looking at the ceiling, she exhales.

“Wow,” Rabab smiles. “I’ve never answered that question in my life!”

“These ideas of the natural environment and the non-natural, the natural and the man-made… are constructs,” says Rabab.

“That’s not to say that there are parts of the planet where there isn’t human impact, but actually, largely within modernity – and pre-modernity – all of these things overlap.”

Rabab’s notion of environment is echoed by many environmental justice organisations and activists, the origins of which were born out of the 1960s civil rights movement – where activists recognised that environmental issues were social issues, and more specifically, civil rights issues.

These ideas of the natural environment and the non-natural, the natural and the man-made… are constructs…That’s not to say that there are parts of the planet where there isn’t human impact, but actually, largely within modernity – and pre-modernity – all of these things overlap.

According to Dr Jen Iris Allen of Cardiff University’s School of International Relations and Politics, we are now more aware of how these issues overlap.

“We know now in a way that we didn’t know, or didn’t understand, even 15 years ago, all of these connections between race and environment, or gender and environment,” says Dr Allen.

“Those who are most marginalised in society are impacted the most.”

In the mid-1980s in Los Angeles, California, authorities proposed to locate an incinerator in a majority black and Hispanic neighbourhood. The people living in this area mobilised to protest the incinerator, and, in the knowledge that strength comes in numbers, they tried to build a coalition between themselves and some of the bigger, more established environmental organisations, known in the US as the ‘Group of Ten.’

They failed to gain their support however, as some organisations in the ‘Group of Ten’ declared the situation a “community health issue” rather than an environmental concern. Simply put, they didn’t see it as their problem, and they didn’t recognise the intersection at which environmental issues overlapped with social.

Drawing upon this anecdote, Razmig Keucheyan comments on how there is a tendency to view the environment as lying “beyond the relations among social forces.”

He argues however, that in reality “nothing could be more political.”

Political space

We see this politicisation of space at work in many of our cities in the UK, and the pattern is repeated the world over, with poorer and usually ethnic-minority communities living in the city – and as a result, often exposed to far higher levels of air pollution – and wealthier, largely white communities, relocating to the outer-areas and suburbs.

This concept was best known as “white flight” in the 1960s and 70s, and recent research shows that in the US at least, this is still a continuing phenomenon.

Right here in Cardiff, the highest black and minority ethnic populations are more to the centre and south of the city- wards such as Riverside, Grangetown and Butetown.

While Cardiff has a high percentage of green spaces and parks, when you look at a map you’ll find its green spaces are in far greater abundance to the northern and north-eastern suburbs of the city. The top three parishes in Cardiff with the greatest percentage of vegetation are Lisvane, Old St Mellon’s and Pontprennau – all areas with low rates of deprivation and poverty, and coincidentally, far “whiter” populations.

Unsurprisingly, the bottom three parishes, or those with the lowest percentage of vegetation, are Riverside, Adamsdown and Splott – all of which have much larger black and minority ethnic populations and higher rates of deprivation.

A lack of tree cover and green space not only limits areas for children to play in or families to enjoy but means greater suffering for those living in the city as global temperatures rise and heatwaves become more frequent.

A recent study published in the New York Times found disparities of up to twenty degrees across different parts of the same city, “with poor or minority neighbourhoods often bearing the brunt of that heat.”

This was due to the fact that paved surfaces and buildings had an “amplifying” effect on the heat, while those areas with tree cover and green spaces “cooled down” surrounding areas.

“[I] hate thinking we escape the city because that’s when it’s natural, and we get out into the rural world,” says Rabab.

“Rurality and also the country is deeply informed by colonialism, and deeply informed by structural power and wealth, and ownership of land and control of land.”

Conserving land and ecology is a huge part of the environmental movement, with public figures such as David Attenborough increasing awareness around the pollution of our oceans, the endangerment of certain species and the deforestation of resource-rich rainforests.

But the idea of conservation can be traced back to colonial settlers, who saw this simply as a way of prolonging exploitation of the land.

Conservation of the natural world is embodied both today and historically within the National Park Model, which has spread worldwide, from the still blue waters of the Lake District in Northwest England to the golden plains of the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania.

Now we’ve created this thing called a park…And it’s a national park, and you’re not allowed to come back in unless you pay the ticket.

The first national park was established in Yellowstone, US, in 1872. Situated mainly in Wyoming, but also straddling Idaho and Montana, it offers cascading waterfalls, spluttering natural geysers and is home to hundreds of wildlife species.

But behind its natural splendour a dark history lurks.

Yellowstone was “gifted” to the American nation by Congress as a “pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people” yet approximately 26 indigenous tribes who had lived, hunted and inherited the land for hundreds of years were removed, with president Ulysses S. Grant declaring that anyone found to settle on the land “shall be considered trespassers and removed therefrom.”

“The term a Nation’s Park was coined by a painter who wanted to keep this pristine aesthetic,” Dr Allen explains, referring to George Catlin, famous for painting indigenous tribesmen and the natural American landscape.

“[But] they totally ignored how that park came to look that way – [after] generations and generations of interaction with Shoshone and Blackfoot and Cree peoples.”

According to Dr Allen, we only really consider connections between people and nature when there’s a way in which “environment serves people.”

Eliminating the very people who maintained the land and balance between human life and nature has serious consequences, Dr Allen outlines:

“Humans and nature have always interacted – so the forests grew up faster and more dense because people were cutting them.”

The Guardian reports that most of the world’s 6000 national parks and 100,000 protected areas were created by the removal of indigenous tribes, and this is only likely to increase as the UN aims to meet its goal of protecting 17% of land by 2020.

“Now we’ve created this thing called a park,” says Dr Allen with a sarcastic smile. “And it’s a national park, and you’re not allowed to come back in unless you pay the ticket.”

Cause and Effect

The conservationist effort may have good intentions, but it often ignores the indigenous tribes who have historically shared the land with other forms of life and have forged a deep connection with nature.

Rabab believes that we can learn a lot from indigenous communities around the world, who have remained for generations despite the violence and brutality of colonialism.

While indigenous peoples make up only 5% of the global population, the land they own and inhabit spans 38 million square kilometres – the equivalent of a quarter of all land outside of Antarctica.

Rabab believes their legacy is owed to an ability to “conceive environment as total” – they understood the ways in which environment, politics, spirituality, community, other species, and structures of power, interacted, she says.

On the other hand, Western countries have viewed the natural world as a commodity – even when seeking to “conserve” it they have found ways in which to profit off of it.

In order to recognise how we got to this place – facing a climate “crisis”, which much of the global south is already in the midst of – Rabab says we must recognise “the deep, deep causal reasons for why we have a pillaging of the Earth’s resources.”

These reasons she says, stem largely from white privilege, colonialism, patriarchy and consumerism – all of which have created a world “where some have, and others don’t.”

In 2015, a study published in the Journal of Industrial Ecology found that consumerism – from food, to clothes, to gadgets – is responsible for as much as 60 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, and between 50 to 80 percent of total land, material and water use.

The study identifies that food accounts for nearly half of household impact on land resources, and 70% on water resources, “with consumption of meat, dairy, and processed food rising with income.”

Consumerism has been accelerated by the digital society we live in – where products, food and clothes are marketed through social media. Dr Allen calls it the “feedback effect”- where certain lifestyles are “exported” around the world.

“Rising middle classes in developing countries is great news, but well, that means I want steak, and I want wine, and I want air conditioning. And all of these things that we take for granted,” she says.

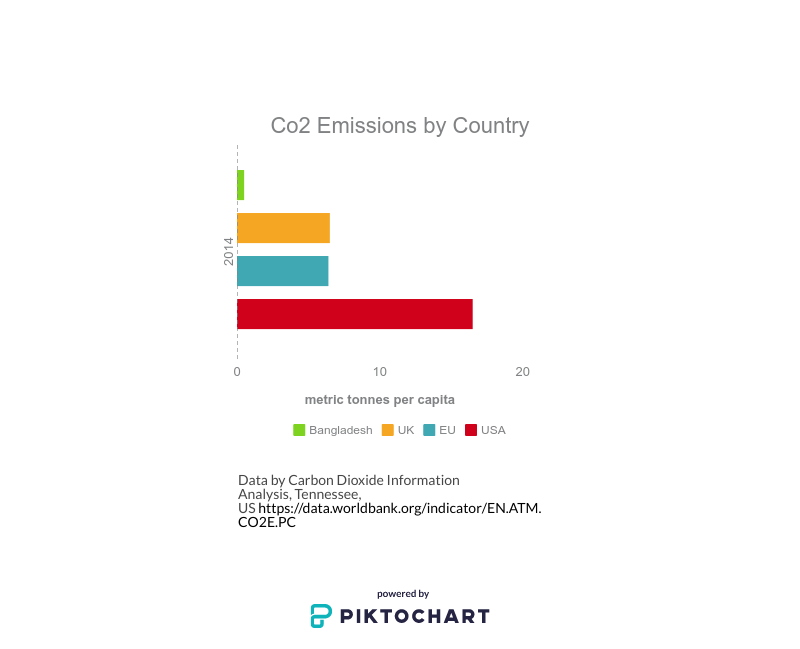

It goes without saying that consumerism is far higher in richer countries – the US has a per capita emissions amount of 18.6 tonnes CO2 equivalent, whereas the world average is 3.4 tonnes.

“If we’re not willing to give it up, they won’t be willing to give it up either,” says Dr Allen.

“It’s a really interesting question of what’s fair, and what’s blatantly hypocritical?”

For some, the only way of coping with the guilt of individual responsibility, is through activism.

I feel individually quite powerless, but society continues as it does because, collectively, we let it.

Retired Headteacher Sian Vaughan, aged 54, never expected to become an activist, and admits she “know[s] very little about political philosophy” but says “[she] was inspired by Greta, incensed by those criticising her and ashamed at [her] inaction.”

She found herself joining Extinction Rebellion, the international movement using “non-violent civil disobedience in an attempt to halt mass extinction and minimise the risk of social collapse.”

“I feel individually quite powerless, but society continues as it does because, collectively, we let it,” she says.

The capitalist system thrives off our idleness. Smartphones now have an addiction power that rivals drugs, and one-click shipping means we think little about where something came from, how it came to be, or what trace it leaves behind when we discard of it.

As Rabab puts it, it “[is] a system which requires a level of disconnect.”

If we look at a corporation such as Amazon – which we now know has enforced terrible working conditions, whereby, in extreme cases, workers have been forced to urinate in bottles as they aren’t given toilet breaks – for many consumers, the ease at which we can go online and find an item for a cheap price, purchase it in one-click and have it shipped to our doorsteps in a matter of days, outweighs the reality of acknowledging the “real cost” of such a service.

Rabab gives her own example: “There were points in my life, [when] I put petrol in a car with full knowledge that doing that has a causal link back to people in my homeland, who were suffering as a result of wars waged because fossil fuels were in the ground in our country.”

But while groups such as Extinction Rebellion seek to unite all of humanity against a climate disaster, Rabab also believes that some of us are more responsible than others for the consumerism which has ultimately driven a climate breakdown.

Bangladesh’s CO2 emissions per capita are 1/13th of the UK’s and just 1/33rd of the United States, yet global warming is causing inconsistent weather patterns in the country – from extreme drought seizing crops and agriculture, to heavy flooding caused by the run-off from the glaciers in the Himalayas.

The National Geographic reports that every year, “an area larger than Manhattan washes away” from Bangladesh. It is hard to imagine an area of this size washing away from a developed country and the world standing by to watch.

But for Sian, the people she fights for are closer to home, even though climate change has barely kissed the UK yet.

“I think of my daughter and of the many children I have taught. I find it hard to contemplate humanity, collectively, laying waste to the natural world in an act of suicidal stupidity,” she says.

Many activists – particularly retirees – have joined climate marches and demonstrations in the name of future generations. According to Dr Allen, last year’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report was what really started “intergenerational justice” – where older generations feel a sense of responsibility towards future generations.

The report projected the impacts of global warming of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, listing drought, flooding and extreme hot and cold temperatures among the likely effects.

“It put a timeline on it,” Dr Allen says. “The amount of years – it is actually a human lifetime. 31 years – we’ll be alive then.”

On the other hand, Rabab says that the simplified idea that all of humanity are headed for extinction – as expressed by Extinction Rebellion – is flawed.

“This idea of like, ‘Man, you know, we’re all responsible.’ Again, it’s really easy to say, Man as a species. And when we say that – humans as a species, we basically apportion responsibility to everyone.”

Rabab also says that the focus on the future misses the point that people are suffering right now. In May, her organisation, Gentle/Radical, signed an open letter to Extinction Rebellion written by environmental justice group Wretched of the Earth. The letter was published on the website of left-wing publication Red Pepper, and gathered the support of over thirty signatories from various grassroots organisations.

“Greta Thunberg calls world leaders to act by reminding them that ‘our house is on fire,’” the letter reads. “For many of us, the house has been on fire for a long time…”

I put this point to Sian, asking her to what extent she feels Extinction Rebellion place emphasis on the imminent threat of climate change on communities in the global south.

She says she thinks the group and Greta Thunberg do talk about current suffering but also identifies an issue with the media – and the audience.

“I do find it depressing that people can fail to respond to news of casualties overseas,” she says. “As if Cyclone Idai is just the kind of thing that happens ‘over there’ and nothing to do with ‘us’ at all.”

However, Sian also notes the role of cultural proximity, suggesting that “as humans, we are more likely to react to our children or our homes being threatened that those of other people.”

She says the media refuse to make the link between natural disasters and climate change, adding “[that] even if it did, I suspect that, unfortunately, people would only demand action if there was also the message of, ‘You next.’”

What next?

While Sian sees direct action as her only hope, Rabab sees it as futile unless the deeper issues of capitalism, colonialism and white supremacy are addressed.

“I don’t see how you can forge a movement for radical shift around the environmental crisis, if you’re not dealing with white supremacy and patriarchy,” she says. “If you don’t fully understand what the real causes are, you cannot find the solutions.”

If you don’t fully understand what the real causes are, you cannot find the solutions.

When I ask Rabab where this disconnect stems from, she replies that it comes from white privilege, where many people are not even aware of the ways in which race and class operate within society unless they are on the receiving end of structural oppression.

“It’s very hard for people to go: ‘the entire system upon which I experience day-to-day life, have access to privileges… [am] able to consume in ways that constantly have a cost on a minute-by-minute basis to someone…on this planet – that cost I don’t have to think about because that’s what my privilege gives me.”

One thing that strikes me as we are having this conversation, is that a lot of the sensitivity around accusing somebody of being privileged, or being part of a racist system or organisation, is that we are raised to believe that racism is direct and explicit – a racist slur or an obvious discrimination – but we aren’t really taught about the subtleties of structural oppression and racism.

Rabab even boldly points out her own privilege as a “white-passing woman of Arab heritage.”

“I have racism within me,” she insists. “I have it in me, I am racist, in all kinds of ways. I often don’t even realise that I’m a product of this society.”

Rabab believes that these implicit structures of race and class operate within social movements too, which is why she’s stepped back from direct action, despite once being a regular at anti-racist and anti-austerity marches.

She adds that many movements she’s been a part of have fallen apart or have failed “to swell the ranks” and entice new people mainly because of the power dynamics. While most groups start off with a collective “togetherness” against the state, Rabab says movements have a tendency to fracture.

“The power dynamics…operate across racial, gender, class lines. We either don’t want to look at it – It’s too uncomfortable, or we don’t have the strategies to deal with it,” she says.

While much activism seeks to create a sense of community through empowering and uniting like-minded individuals, it isn’t always welcoming for people of colour.

“That’s another layer of privilege you’re getting, just by being part of this movement,” says Rabab. “When you actually think you’re doing things on behalf of others, it’s generating more benefit for yourself.”

Rabab also says that the people who will be worse off from climate change are “largely absent” from the protests and meeting groups, mainly because Extinction Rebellion has failed to engage with them and continue to use tactics such as arrest that simply aren’t an option for people of colour, who already face everyday discrimination from the police and authorities.

When I ask Rabab what she thought of the group’s “Summer Rebellion” in Cardiff, she says “[she] thought it would be a bit more rigorous.”

“They’d have done better in my mind to go out and do five deep-rooted days of community outreach and have an actual programme- a strategy – of how you’re going to go and have conversations with people in the community.”

The question is if it’s too late – which is the worrying part…Which is maybe why you know, gluing yourself to something kind of makes sense?

But how do we do this when the earth is currently a ticking time bomb?

“The question is if it’s too late – which is the worrying part,” says Dr Allen.

“Which is maybe why you know, gluing yourself to something kind of makes sense?”

Dr Allen says she suspects Extinction Rebellion feel civil disobedience and direct action is the group’s last resort to protest the government’s incrementalistic reaction to climate change.

Sian confirms this. “Nothing else has worked…I am acting because it is the only hope,” she says.

But Dr Allen does recognise that there are issues within Extinction Rebellion, noting that civil disobedience “is a tool in the toolbox,” but that the group must now decide how they go forward – do they broaden their base of people through a change of tactics, or do they stick with the same strategies?

“Every movement makes strategic choices, but it does mean that they’re overlooking a lot of voices,” she says. “I think the important thing is to show how environmental issues and issues like poverty are linked, but I think this gets back to…is it individuals, or is it structure?”

It seems like everyone I speak to is reading from the same book: there is a definite recognition that radical change is necessary – the differing opinions are more around how we achieve it.

While my conversation with Rabab has gone deeper than any other I’ve had about the environment, I’m also conscious of the fact that she’s been a practicing Buddhist for the past 25 years, and has spent extensive amounts of time reading about spiritual “work” and reflecting upon her own shortcomings – which may not be realistic for your average consumer.

But I think there is something we can gain from her insight – I certainly walked away thinking a little more deeply about the climate debate – the nuances of which are so often simplified into humanity and nature, people and government.

Extinction Rebellion is no doubt a powerful movement which has both the

manpower and resources to really challenge governmental power, but it’s clear

that if it achieves anything, in order for there to be a radical change, there

needs to be a shift around the voices that lead the fight – and perhaps the

only way this is possible, is with some difficult conversations around

privilege, class and the legacy of structural oppression.