Adult ADHD is on the rise, but who is to blame for the psychostimulant explosion on university campuses?

“Hey, do you know where I can get some Adderall?”

“Stand in the middle of campus during exam season.”

For Alex W, a third year university student studying engineering at McGill University, this text exchange was not an exaggeration. At times of pressure from her studies, finding illicit psychostimulants— medications used to treat Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD)– was an easy way to make sure she was focused.

“It makes the work more interesting,” says Alex. “It doesn’t make you smarter, but at least you’re able to concentrate for hours.”

She has never tried to get her own prescription or sought an ADHD diagnosis, but knows others who have.

“A friend of mine tried to do it through the university,” she says. “You can make a lot of money and it didn’t sound hard to get a diagnosis.”

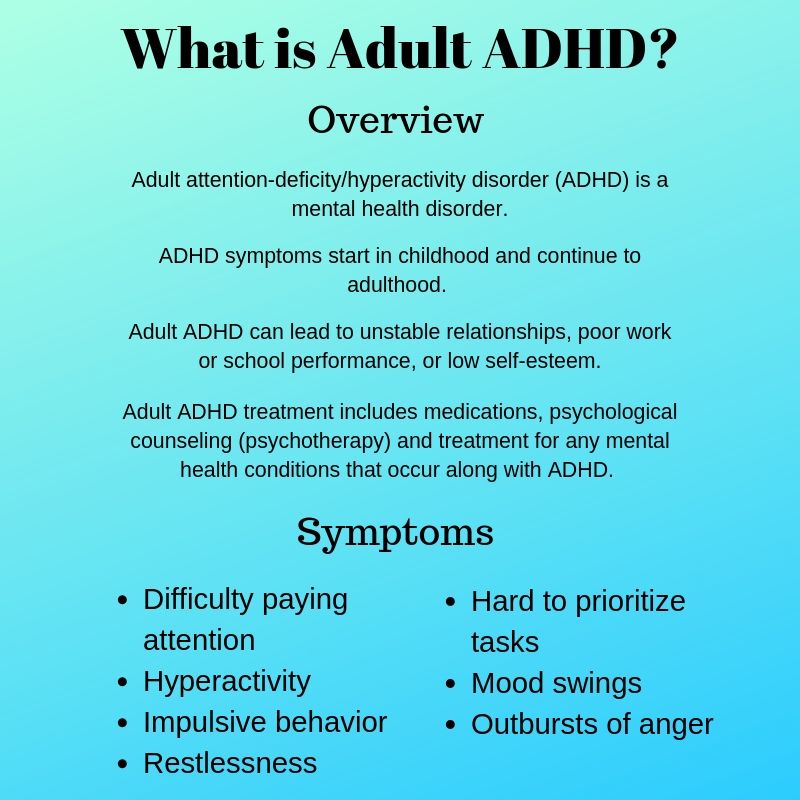

The presence of psychostimulants, colloquially known as study drugs, points to a larger issue in Canada: the overdiagnosis of ADHD in young adults.

Dr. Ben Bordoff, M.D., who worked at a university mental health in Windsor witnessed this problem first-hand.

“One of the things I was noticing was people presenting with ‘I can’t concentrate’ as their chief complaint, and a lot of students were being classified as ADHD. I found this to be an incredibly difficult diagnosis to make,” he says.

Without access to childhood records or a medical history of the student’s life, university student health clinicians are often left to rely on a student’s recollection of their childhood experience.

“You’re kind of working in the dark. And then you’re supposed to give them a schedule 2 pharmaceutical? That’s the most abused category of drugs. A psychostimulant? This seems really problematic to me,” says Bordfoff.

Considered dangerous because of their risk of abuse, Schedule 2 drugs include ADHD medications alongside more volatile substances like morphine and oxycodone.

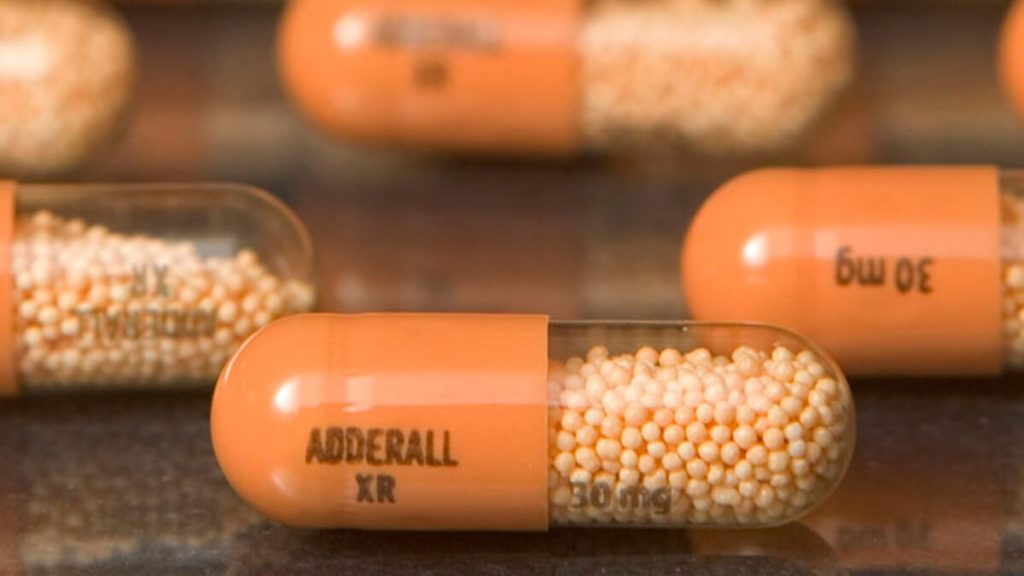

The reality is that many of these psychostimulants (the most common being Adderall XR, Concerta and Vyvanse), are being diverted and recreationally used. Although only 3 percent of adults have ADHD, as many as a third of college students admit to using prescription psychostimulants— and the same amount admit to selling them.

The going rate for a single pill of adderall during exam season is ten to fifteen dollars in Canada and are readily available for those who are looking to buy.

“If you have a contact it’s really easy, but it depends how many people around you are doing it,” says Alex. “At one point everyone was, so it was super easy to find.”

But the potential to profit and an increase in concentration at school are not the only incentives for being diagnosed ADHD. Academic accommodations including extra exam time, deadline extensions, and bursaries are among the benefits for those diagnosed.

“Anything in psychiatry or medicine with a high external incentive, you must be somewhat skeptical of,” says Bordoff. “I’m not saying [the students] are a bunch of feiners. I think they lull themselves into believing they have something that they probably don’t.”

No test has yet been found to accurately distinguish individuals with ADHD from non-ADHD subjects and with the proliferation of online information about various diagnoses, students often come prepared with an understanding of their symptoms.

“Often times they’ve looked at things online and have an idea of what they think is wrong with them,” she Martina Power, M.D. “These are usually genuine concerns.”

Both Power and Bordoff point out that student patients are more likely to feel there is something wrong with them when those around them are receiving ADHD diagnoses. Allen Frances, a psychiatrist who has written extensively on the subject, calls adult ADHD diagnoses the current “fad-du-jour.”

He believes there are two reasons why ADHD has become a “fad” diagnosis. The first, is that attention problems caused by other psychiatric illnesses can be mislabeled as ADHD; and the second, is that normal distractibility is part of human nature— most adults want to focus better.

This has led to a sixfold increase in the amount of psychostimulant prescriptions made in the U.S. during the last decade and the largest market is young adults over the age of 20. This is due in part to the fact that criteria for diagnosis is becoming looser.

“It’s becoming more difficult to accurately diagnosis adult ADHD because the criteria seems to be getting broader,” says Power.

The World Health Organization has created a self-screening questionnaire that helps individuals determine whether they have adult ADHD, but according to Ben Bordoff these tests are ineffective.

“These self-screening questionnaires are completely useless,” he says. “Everybody in university wants to focus better, they want to concentrate better, and they want to get as much done in the shortest time possible. This does not mean you have ADHD.”

The tests contain questions relating to struggles that many people face on a daily basis, including: “How often do you have problems remembering appointments?” and “How often do you misplace things?” These questions lead to false positives rather than testing specifically for a particular diagnosis.

“The correct thing to do would be to specifically diagnose it with something that has a high specificity,” says Bordoff. “But that isn’t done. They just take these questionnaires and check, check, check— if you want the psychostimulants you’re going to get them.”

According to one study, the prevalence of feigned or exaggerated ADHD in university settings has been estimated to be as high as thirty to fifty percent.

Another force behind the rise of adult ADHD diagnoses is the rise in marketing by pharmaceutical companies pushing psychostimulants— so much so that investigative journalist Alan Schwarz has called it “big pharma’s manufactured epidemic.”

“The sixfold increase in the space of a decade coincided with aggressive marketing of these psychostimulants in the midst of really no other drugs available in the pipelines for those pharmaceutical companies,” says Bordoff.

Still, points out Power, big pharmaceutical companies are in the business of pushing their medications. “You can’t blame a tiger for being a carnivore,” she says.

However, the companies still have an “outsized influence on medicine, particularly psychiatry.” When it comes to adult ADHD marketing, one U.S. company went so far as to recruit the lead singer of Maroon 5 for their campaign. “It’s your ADHD,” the ad concludes. “Own it.”

Although direct-to-consumer marketing of medications is illegal in Canada, drug companies were able to get psychiatrists to speak at sponsored events about the newfound prevalence of ADHD in adults— a phenomenon that didn’t begin until the 1990s.

Reporter Alan Schwarz described one such meeting sponsored by Shire to promote Adderall, in which a psychiatrist was paid to give inaccurate information about ADHD to the crowd of nearly eighty doctors.

“It’s the GPs minds that they want,” says Bordoff. “Psychostimulants are now more likely to be prescribed be generalists than mental health specialists.”

The overdiagnosis of adult ADHD, whether by a seasoned psychiatrist or through a quick visit with a general practitioner, can have dire consequences.

“When the real diagnosis is missed, this can have horrible implications for the patient,” says Martina Power. “For example, mislabeled ADHD causes great problems when people with bipolar disorder receive psychostimulants.”

Bordoff agrees, “Becoming addicted to these psychostimulants can fuel psychosis. Patients will have no insight into what they’re taking, which can launch a drug-induced manic episode. That’s a pretty risky thing.”

Even with these risks, in a survey of university students, it was found that using psychostimulants did not alone solve academic deficiencies. Better study habits and a healthy lifestyle can help to close the “achievement gap” between those with and those without adult ADHD.

“It really speaks to a larger concern about the overmedicalization of daily life,” says Power. It’s a “schism in the profession.”

“People are very quick to look at things as ‘chemical imbalances’ and not one looks at who this person is, where they come from, and what experiences shape them— how do they process the world around them intrapsychically?” says Bordoff. “I think that’s a dying art.”

Chemical imbalance or not, for the Alex W. the availability of psychostimulants gives her the “edge [she] needs” to make it through university, which she describes as a “pressure cooker.”

“One you take it, you want to take it every time you have a hard or difficult situation,” says Alex. “Why not just take it to help yourself? It costs as little as a meal. I wish I could take it now— I have to do my taxes.”