In a time of widespread secularism, why do people still choose to complete a 1,400 year old, day-long pilgrimage?

Every year in May, pilgrims set off from Bristol Cathedral and trek towards a small church on the eastern banks of the River Severn. Though a moveable feast to some degree, the walk typically occurs the anniversary of the death of St Augustine of Canterbury, his feast day being the 26 or 27 of May, depending on nomination. This year, on May 25 the faithful walk in recreation of the twelve-mile journey of St Augustine of Canterbury in 603CE, on a mission to clear up dogmatic and practising differences between Roman Catholic and Celtic Christian churches. The alleged meeting between Saint Augustine and various Welsh bishops was unsuccessful, failing to bring the Welsh church into union with Rome.

Yet the pilgrimage embraces the theological disagreements that most distinguished Celtic from Roman Catholic practitioners. Celtic Christians tended to reject the asceticism that encompassed and, in the views of many historical and contemporary critics, evidenced the corruption of the Church. From the steps of Bristol cathedral, the route to St John’s Church in Aust is decreasingly adorned with not just the Cathedral’s treasures but the cities wealth too, ending ultimately in a humble but still aesthetic chapel with few gratuitous tokens of worship.

Many people were critical of the donations made after the Notre Dame fire in April this year, but the vast wealth of the church has always been a point of contention. Some estimates of the total sum of pledges made equal £519-million, money that some argue would be better spent on charities and infrastructure investments. To some extent the walk from Bristol to Aust represents a spiritual rejection of that wealth and the labour applied, ostensibly in celebrating God, but equally in displaying wealth. To step onto this pilgrimage is to step away from a place where it is admittedly hard (and harder still for an agnostic) to see a Godly world. Though the Cathedral is an awesome sight, as is many a building in the city, it is impossible to ignore the vast contradiction between a prophet who cast out money lenders and exclaimed, “It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the Kingdom of God”.

There is something of a return to Eden upon leaving the city centre. Past tired, coldly efficient industry parks, loud roadways and into the open. Informal, rugged routes cut through bright green fields which at this time of year are pimpled with dandelions. At a certain point the familiar sounds and smells of the urban area are gone. For the religiously inclined this is to some extent the quintessential pilgrimage experience. By entering a rural landscape, one can slip into a timeless place where the only sign of the industry of humans is the odd stone wall. In a 2010 address Pope Benedict XVI described this as “encountering God where he revealed himself”, an ethereal task made easier by the absence of tarmac. Though its likely many people complete a few miles of the route every day, the deliberateness of the act is what separates the practice from a walk in the park.

According to the most recent census, the second biggest religious affiliation after Christianity, representing 59.5% of the country, is those who do not have a religion or at best only nominally participate in one. A group that makes up over a quarter of the United Kingdom’s population. So what is the lingering appeal of pilgrimages across the world, in the face of growing secularism?

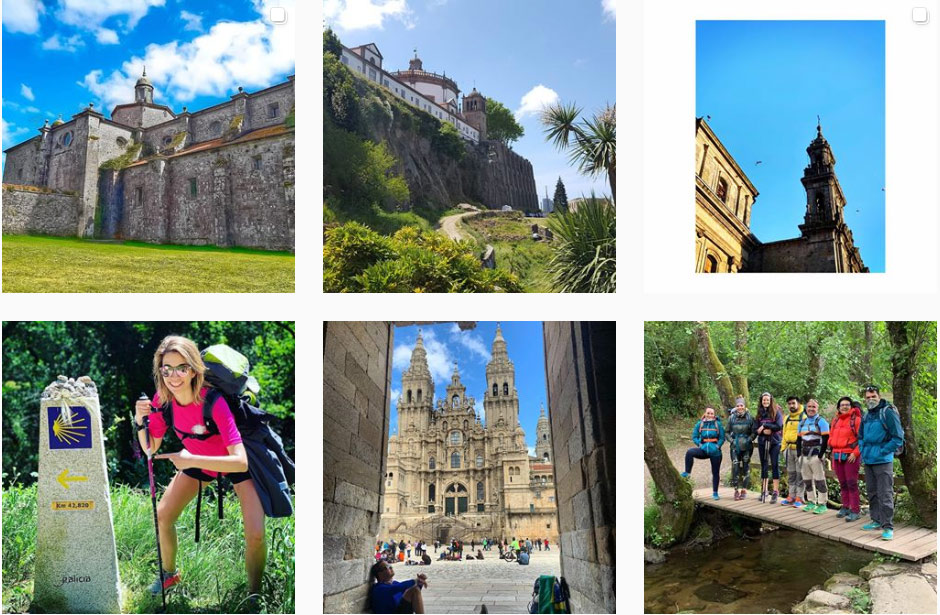

A more famous and popular pilgrimage, St James’ Way (or Camino de Santiago) has seen over 1.2million Instagram posts detailing the route and the people undertaking it. But this doesn’t seem to come from any sense of social-media narcissism that might be expected. Nadia Caidi, a senior professor at the University of Toronto has examined the effects of the social media age on the act of pilgrimage. Nadia says that selfies in particular, “capture and document pilgrims’ experiences, contribute to their meaning-making, enable the sharing of memories with loved ones, and attract online followers”. Pilgrimage seems to capture a somewhat unique USP in social-media, having no particularly gendered audience, no racial majority and surprisingly no age basis either. The images of happy-faces, despite the visible dirt and sweat, in beautiful surroundings are no doubt endearing and hit on perhaps the biggest motivator of pilgrimages besides the faith itself.

There are many practitioners it seems, who see a world in lapsing faith. The use of social media allows those on pilgrimage to define their religion for themselves. Presenting the human face of what are now often seen as institutions, and little else, a service that Nadia finds essential in a time where religious in tolerance presents many dangers and informs some of our worst populist leaders. Detailing pilgrimage via social media, “creates opportunities for self-representation and community building” says Nadia.

Community is something to be found on the route to Aust too. People have travelled from as far as South Africa and the United States to complete the pilgrimage to Aust. Michael who travelled from Texas to complete the walk describes the process as “a walking prayer in its most basic form, incorporating the individual real life situations of all involved”. Michael learned of the walk because of St Augustine of Canterbury lends his name to Michael’s local church in its abbreviated, ‘St Austin’. Though a popular eponym in the Christian community, and despite his (likely) Italian origin, the Oxford Dictionary of Saints has called Saint Augustine ‘an apostle to the English’, and a great influence on the nation’s faith. As a result, this very brief pilgrimage holds a great deal of significance for the faithful in England.

Pilgrimage does force the practitioner to conjure up images of what the local landscape might have looked like in the seventh century, how it must have felt to cross stony paths on flimsy shoes and question what might have been going through the minds of Augustine and his accompanying monks. In Acts 17:24 it is claimed that, “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man”. In trudging overgrown grass and hearing the sounds of nothing but birds and your own footsteps, the pilgrim’s mission to ‘find God where he reveals himself’ becomes more understandable. Tired legs make Bristol city centre feel a world-away. To abandon walls turned black by exhaust smoke, the towering Cathedral and the other temples of men is to find a serene feeling.

Whilst few, if any, will experience a road to Damascus style conversion, there is something to be said for the practice even if your beliefs exclude an omnipotent and omniscient figure. Typically, those who complete the pilgrimage to Aust are already practicing Christians, but the route is enjoyable and freeing as all escapes from urban-centres are and that may be the most significant motivator for pilgrimages in the modern-era, especially for local and incredibly manageable routes like the one to Aust.

Simply put: it’s nice to get out.