On their own, they’re an inconvenience. But Christian S. Phelps finds that frigid weather, frail bodies, and faulty benefits, altogether, can make for a wicked winter in Wales.

“You’ve come to help us, have you?”

The woman asking was in her 90s, smiling widely but not fully understanding why I was there, in a North Wales sitting room, joining her peers for morning coffee.

It doesn’t have to be snowing to see how hard the winter is for over-65s in the Welsh mountains. My trips from Cardiff to Caernarfon, over four hours of popping ears as I drove through the peaks and valleys, exposed me to the lone houses in North Wales that rely on a single-track road down a steep slope to access the nearest village.

At the local Age Cymru office, not far from the coast, elderly citizens arrive via shuttle for social interaction, refreshments, and general assistance. Many of them require one-on-one help getting from the shuttle to their favourite armchair.

“If they live alone, and they don’t have a support network of family, friends and neighbours,” says Angharad Phillips, Health Initiatives Officer for Age Cymru, “food costs, transport, that’s huge—that’s the difference between quality of life and life or death for some people.”

When I finally arrived at the local Age Cymru office, I’d seen these homes up high, some of them heated by oil and others by wood fireplaces. I’d wandered the narrow, curvy road down to the coast and into the main building, where I was introduced to a group of 10 to 15 elderly locals as someone who wanted to chat about their winter heating bills.

No one batted an eye. I guess it’s something they talk about often.

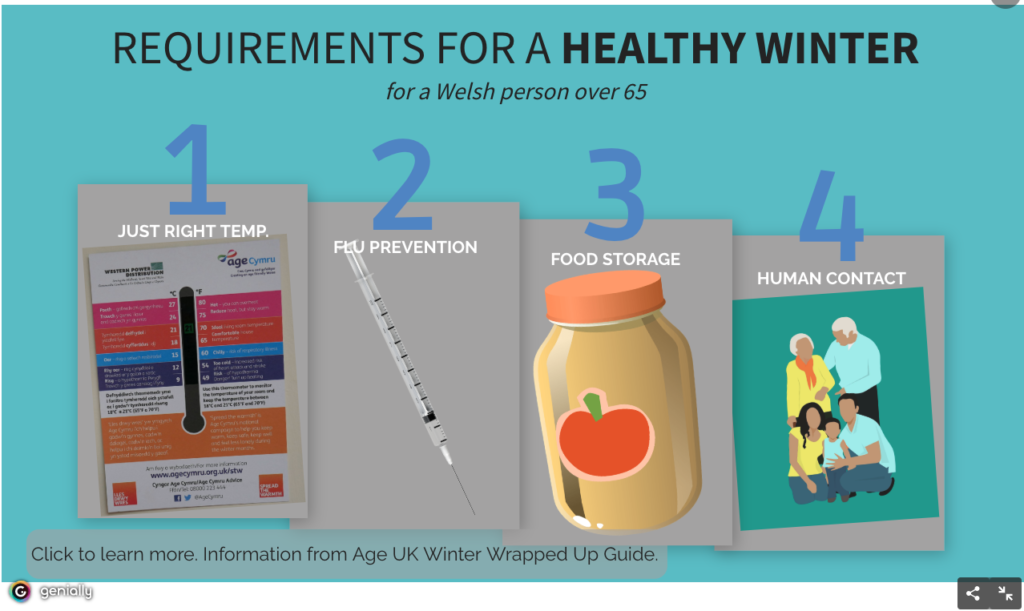

Ms Phillips co-ordinates a “Spread the Warmth” campaign focussed on helping Welsh pensioners know how to stay healthy and safe when the weather is cold. But widespread poverty and isolation make her job more difficult.

“Some people who are living in fuel poverty are having to choose between heating and eating. So they’re having to choose whether they heat their home or whether they eat a hot meal,” she says.

“And that’s really alarming.”

She says that chronic medical conditions have devastating effects in the winter, particularly for people who need extra food and heat but may not be able to afford it.

“It is incredibly tragic,” says Hywel Williams, the Caernarfon-based Plaid Cymru MP representing these northern dwellers and perhaps the most vocal critic of the Cold Weather Credit system, which has caused some of his constituents to go without week-by-week assistance. He knows the consequences of heat-or-eat well.

Mr Williams recalls the heartbreaking story of one man’s fateful experience with welfare last winter, having spoken to numerous residents in his constituency whose relatives suffer in the cold.

“This guy was assessed for disability benefits. The assessor didn’t realise that he had a brain injury, and he couldn’t explain himself. He died in January,” Mr Williams says. “He’d died in the kitchen, and there was no heat, and the refrigerator was empty. He just didn’t have the money.”

There was no heat, and the refrigerator was empty. He just didn’t have the money.

Hywel Williams MP

Excess winter deaths are a measurement of how many more people die in the winter than in other seasons, due to issues like poor housing conditions, weakened immune systems, and underfunded resources. Excess winter deaths have risen in recent years to levels not seen in over four decades.

Heat-or-eat situations, when someone’s home is freezing and refrigerator is empty, contribute to this steep rise.

Studies have shown that cold weather and austerity have direct impacts on people’s health. Social scientists have also found that countries like Wales, where the temperature only sometimes drops below zero, are less equipped to help citizens through the winter than nations like Norway, where the weather is more consistently frigid, infrastructure is better and services are more prepared.

My own grandmother lives in northwest Wisconsin, USA, where winters are freezing and no one could survive without daily heat. Last winter, the area saw about 251 centimetres of snow. She depends on significant assistance to afford the winter, when her heating bills would otherwise vastly outweigh her ability to pay them.

Until coming to Wales, hearing from Ms Phillips, and visiting elderly residents in Caernarfon, I had never considered a scenario in which my grandmother doesn’t get this assistance. Here, unlike her home, snow is infrequent and British austerity has permeated society for a decade.

Siân, who lives in a Council-owned home in the valleys north of Cardiff, needed to heat her house all the time last winter to mitigate the symptoms of her fibromyalgia.

But she couldn’t.

“I was only able to put my heating on about two hours in the evening, when it was like, oh, my God, it’s biting my nose off, it’s freezing my face, my skin, my gums are even cold. How can your gums freeze?” she says. “But that’s how sensitive you become to cold when having to deal with four chronic pain conditions.”

I think again about my grandmother, whose house feels to me like a sauna, its heat set to higher and higher temperatures as she’s grown older and lost weight. I wonder how she’d cope if she could only turn it on for two hours on each of January’s 31 days.

“Last winter would’ve been an absolute, catastrophic nightmare, because my bill would’ve been so high,” Siân says. “So in a way, it was better to sit there in the cold, knowing I couldn’t afford to put the gas on, instead of using gas that I couldn’t afford to pay for.”

A heat-or-eat decision in action.

Siân, now 50, has spent years struggling to access the benefits she needs. Since having a child when she was 28, her life has shifted from owning a business to seeking medical diagnoses to relying on public assistance to stay on her feet. She spent years wondering what was causing her pain before finally demanding assistance when her body was unable to work each day.

With chronic conditions like fibromyalgia, the weather can trigger substantial differences in how Siân feels. Some days her ailments are nearly invisible, and others she spends in bed. She sometimes heats her room with candles. Long, lonely winters and an inconsistency in her benefits have demoralised her.

In North Wales, where I sat for coffee, those in the mountains have faced complications with temperature-dependent benefits. The BBC reported in 2018 that many people may have missed out on £25 Cold Weather Credit payments in weeks when the temperature averages below zero. The previous winter, when long cold snaps hit Wales, excess winter deaths spiked dramatically.

I think about the stacks of firewood I saw behind people’s homes in Deiniolen, a settlement nestled into Snowdonia, only a 10-minute drive from the sea but feeling like a different world.

A passer-by there once told me he’d had a fire going just the night before. It was July.

Proudly a Welshwoman, Siân knows that the mountains can get particularly frigid. She also knows the tangible effects of benefit payments like Cold Weather Credit—and what a missed payment could do to mountain dwellers’ lives.

“It would make them more ill,” she says, sitting on the couch where she spends most of her time in the winter. “It’s terrible how the cold affects people with chronic pain.”

Living up high, in old age, poverty, or with medical conditions, a missed payment can have serious consequences.

“Twenty-five pounds to you and I might not seem a lot of money,” Ms Phillips of Age Cymru says. “But I think if you’re, maybe, living alone, on an extreme low-income pension, if you’re living in a home that requires adaptations … people shouldn’t be forced into positions where they’ve got to choose between heating and eating.”

As people age, or become more frail due to illnesses and disabilities, they need to pay close attention to their diets in order to regulate body temperatures and fend off viruses. Ms Phillips spends a lot of time helping pensioners manage a diet that builds their “fuel for the body.”

But Siân knows from last winter that staying nourished is far from easy.

“My diet has also had to change, so now I’m having to spend more on food, for proper food and not processed, artificial food,” she says. “And my weekly gas bill at the time was coming to about £40 because I’m here all the time, and I have to have it on hotter than the average person.”

She tries to get herself out for shopping every fortnight. Last winter is obviously fresh in her memory.

I’ve always known how difficult the winter is back home, and in the back of my mind, I’ve known it was getting harder and harder for people who hit age 65, 75, 85, and beyond, like my grandmother. But being here, with Siân, watching her face tense up as she describes being alone and in the cold, her food access and benefits payments hanging in front of her like the carrot at the end of a stick, brings me a new feeling.

And the issue doesn’t start or end at the wooden door of her lived-in sitting room, or at her Council house which blends in neatly with nearby neighbourhoods.

All these people with problems just can’t get out. They haven’t got no voice.

Siân

“It’s everywhere,” she says. “All these people with problems just can’t get out. They haven’t got no voice.”

When they do get out, many of them do so to seek extra help as they fall further into poverty. When people like Siân struggle with disability benefits, or those in the mountains of Snowdonia miss out on a weekly instalment, their situations can get more desperate.

Those who see this desperation up close know the factors that cause it.

“The two big ones have always been benefit changes and benefit delays,” says Arwel Jones, owner of the Arfon Foodbank serving both coastal and mountainous communities in Mr Williams’s constituency. “In the past 12 months, what we have seen is an increase in the category that’s simply described as ‘low income.’”

Ms Phillips says these trends are everywhere, as foodbank usage grows throughout Wales and excess winter deaths do the same. The need for heating and food are well-documented, particularly for vulnerable people in wintry months. But missing out on benefits can contribute to some of the most devastating impacts of frailty and cold.

People like the man with an empty refrigerator have died, adding to excess winter death statistics. Visiting Siân, and remembering my own grandmother, those stories are far too plausible.

Ms Phillips says these issues have quiet effects on every aspect of vulnerable people’s lives. “You’ve got to see the connection between the emotional, the social, the mental, and the physical sense of emotional health and wellbeing. And in effect, that all leads to quality of life. And who wants to live long into later life if there’s no quality of life?”

Many of the pensioners who welcomed me to Age Cymru were there multiple times per week, relying on the charity not only for their physical health but for companionship. What if they didn’t have access to the charity and its social events?

Living through these icy days and nights and wondering whether benefits would help her has left Siân angry with the British government.

“They started with all this austerity, big, massive rip-off of taking all this money out of the economy, into their tax havens.” She feels that the issues she faces as a benefits claimant, and the issues her northern compatriots face when their Cold Weather Credit payments don’t arrive, come from corruption and greed. “I have been absolutely disgusted. It is a massive, giant rip-off of the poor.”

“There’s more than enough resources on earth, it’s just being very, very badly managed,” she says disapprovingly. “They keep going on about benefits claimants being ‘entitled’—they’re the entitled ones. We’re just eligible.”

Siân does not think highly of the Department for Work and Pensions, but the DWP defends its motivations. “Tackling poverty will always be a priority for this government,” said Ms Vinden of the DWP. She directed some questions about Cold Weather Credit to their Warm Home Discounts scheme, in which the government offers some individuals a discount on their electricity bills.

Nevertheless, Siân insists that the Warm Home Discounts programme has flaws of its own and that when she has expected to receive it, her gas and electric bills have continued to climb.

The government’s outline of the Warm Home Discounts scheme directs applicants to prove their eligibility specifically to their own energy companies—a complicated process in Siân’s experience, as she has switched energy companies over time and qualified for varying benefits as her medical diagnoses and income levels have shifted.

“There’s been a 40 per cent hike in gas and electric bills over these last years,” she says.

The era of austerity has put benefits under a microscope, libraries under threat, and charities like Age Cymru and the Arfon Foodbank under particular stress.

Through isolation, then comes the loneliness.

Angharad Phillips, Age Cymru

Ms Phillips, as someone who spends her professional life advocating for adequate winter resources, says threats to social centres should be taken just as seriously as other public health campaigns.

“It’s the sense of isolation, and through isolation, then comes the loneliness, and then loneliness is equivalent to then maybe smoking seven cigarettes a day,” Ms Phillips says. “We know how bad smoking is for us, and yet we’re still a bit slow to pick up on the fact that these austerity measures are impacting people’s lives so severely.”

No one can dispute the prevalence of austerity in the UK. And few would dare to question its impacts on people’s lives and livelihoods—as needs rise, access falls.

I grew up playing basketball with my grandmother, who now depends upon warm baked potatoes made by other people and a companion to the grocery store.

In recent years, I’ve spent time in her house sweating from the heat she considers normal as her body gets thinner and her needs are greater.

I have taken her grocery shopping from time to time. As her age creeps upward and her health is more fragile, she relies on fewer foods.

My mother regularly takes her to the store for these baked potatoes and other soft foods. If she’s gone, other relatives and friends schedule their visits to do the same. Her diet has gotten increasingly more specific, but people around her are able to accommodate. In the winter, the pavement in front of her house glazes over with snow and ice. It’s difficult for anyone to walk, and she’s all but written off trying.

It’s no mystery what could happen if her heating allowance were taken away, or if all those who take her out to meet people and gather groceries suddenly weren’t around, or if she were trapped in a home disconnected from the nearest seaside villages.

The tone in the room at Age Cymru is difficult to interpret. Pleasantries abound, and even those who suffer from regular strokes and chronic pain greet visitors with smiles, ready to talk about their experiences with heat, family, and health when the weather is cold and their options are limited.

At the same time, no one can plead ignorance to the consequences these issues can have on these people’s lives.

The woman in her 90s continues to grin in my direction. She is already 10 years older than some who have died due to faulty benefits systems, austerity measures, and those who make up the bulk of excess winter deaths.

Sipping our coffee, we all chat briefly about the climate in North Wales, the strategies for dealing with cold weather, and the social advantages of charities like Age Cymru. It’s hard to get deeper, difficult to broach the topic of consequences and the things I know my own grandmother would be struggling with if it were dark and cold in her home today.

Perhaps professionals, like Ms Phillips, have the most direct and realistic grasp on the effects of missed benefits in the winter.

“It’s a death sentence.”