Writers interact actively with readers in network literature, a new form of literature in China, then how is this dynamic relationship impacting on writers?

It is 3 AM in the morning. The cold light of the computer screen is reflected in Huanchu’s tears. She quickly wipes them up and stands up to make herself another cup of coffee.

Huanchu is writing her current novel whose readers are desperate to see the next chapter appear online when tomorrow morning. That means she has 8,000 words left to write and time is running out. When you are an online writer delivering your stories to a hungry audience, you have to work to very tight deadlines.

But there’s one thing guaranteed to slow you down and that’s checking the comments that come in from your readers. All of them have ideas of how the story should develop. For Huanchu some of those comments can be deeply hurtful.

“Of course I watch the comments,” says Huanchu. “I’ve often ended up crying when I’m writing late at night. I used to take some mean comments very seriously, which doubled with the high-demanding output of words everyday nearly ruined me.”

Huanchu is a successful network literature author, regularly posting updates to her stories online to satisfy the demands of a dedicated army of readers. It’s a form of writing that has some similarities with fan fiction, where book fans create additional stories upon popular fictions like Harry Potter.

Differently, network literature writers in China jumped out of the idea of playing around others’ successful works, but built up a wider space instead- to write originally. Fortunately, they met China’s best of age of internet development.

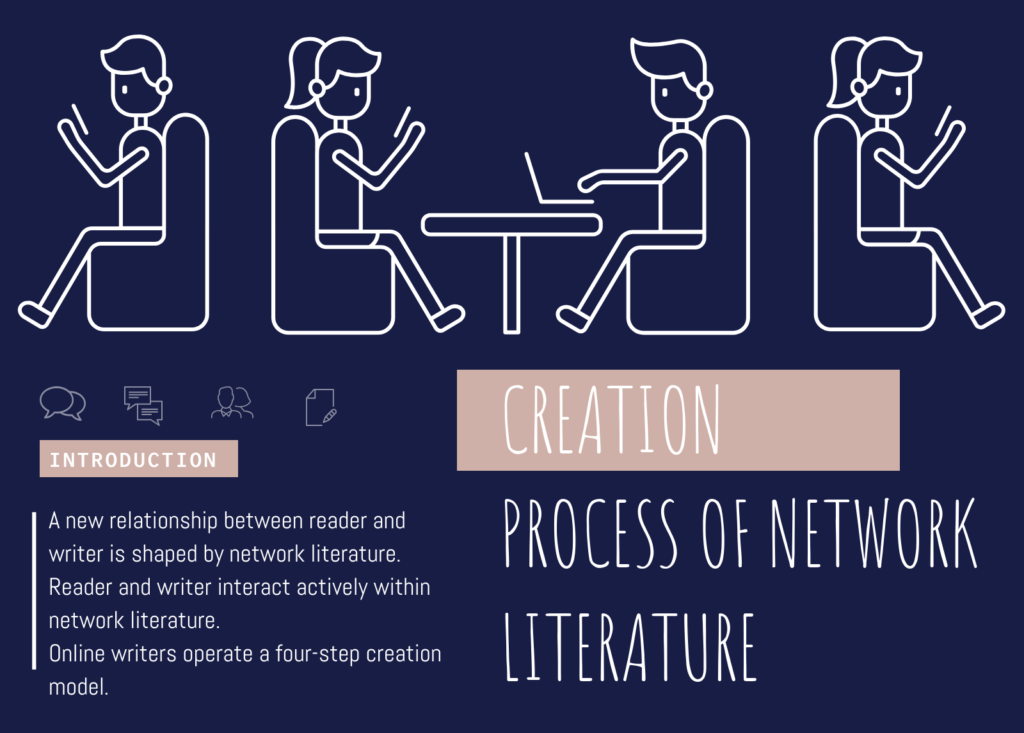

Owning a market size of $two billion, network literature has become a big publishing business in China. There are 14 million authors feeding 400 million readers on various network literature platforms.

On these platforms, the wall between readers and writers was pushed over. A close online relationship between the reader and the writer is formed.

Readers feel free to comment on network literature platforms. Under every chapter of Huanchu’s most popular novel Time Machine: Handbook of Mr.McDreamy, the book fans discussed intensely-

There are angers:

-God, I hate the hero!!

-This guy in this chapter is so disgusting.

And also expectations:

-Would love to see some forbidden romance!

-Could you write some sad plots in future?

Writers can be influenced negatively by polarised comments.

“I can take any criticisms on my written stuffs, but definitely not something beyond that,” says Huanchu. Personal attacks once made her consider about giving up. “That damaged my positivity in writing seriously. For quite a while I thought I was just producing verbal rubbish,” says she.

However, it seems difficult for readers to realise the negativity, who enjoy the conversations with writers.

“I was extremely excited when I first commented the novel I was reading and got replied by the writer online,” says Wuxin, a dedicated reader of Huanchu’s. “It’s like – wow! Did I really talk to the person who wrote so many stories?”

2018 had just witnessed the dynamic interactions within network literature. According to Network Literature Development Report 2018, Spare My Life, Your Majesty became the first network fiction whose number of comments reached one million.

Describing herself as an average online writer, Huanchu says that thousands of fans are active in her fan group chatroom. They discuss newly updated chapters of her novels and share opinions about characters on a daily basis.

Visibly participating in the creation process, readers, for the first time, taste the satisfaction of being heard.

“This in one of the main reasons why I prefer online literature,” says Wuxin. “ Writers were so distant and unapproachable under traditional impression. One could’t even imagine sharing a conversation with them let alone being friends, like between me and Huanchu.”

But is the friendship between reader and writer good for creation? We better have a serious think, as readers are endowed with the power to direct writers.

I always go back to my readers. They are my 100%.

Huanchu , a hardworking online writer

“I rely on my readers’ feedback to change my way of writing so that I can meet with their tastes” says Huanchu. “I have to. That’s how network literature runs. ”

Among the many reasons of losing readers, ignoring readers’ feedbacks is a red warning, according to Huanchu’s experience.

“Readers will leave you with no hesitation if they didn’t get responded,” says she. “There are too many options open to their choices, no writers can be sheltered in a haven. This is not a matter of self-confidence, it’s just reality.”

Such a common sense among online writers is not familiar to traditional writers at all.

“This kind of co-creation is impossible for me,” says Huiwen Zhang, an award-winning novelist who has four books published. “The process of creation is very private and personal in traditional literature.”

Co-creation happens when the boundary between reader and writer blurs, which is not hard to understand under the context of network literature. Just as previous fan fiction writers, most Chinese network writers start as readers. To be a writer or not to be, that’s not a question. The identity is completely switchable in network literature.

“Technically speaking, I started writing since high school back when I was still mainly a crazy reader of network literature,” Huanchu recalls. “I figured that might be something I was into, so I gave it a shot, pretty amateur though.”

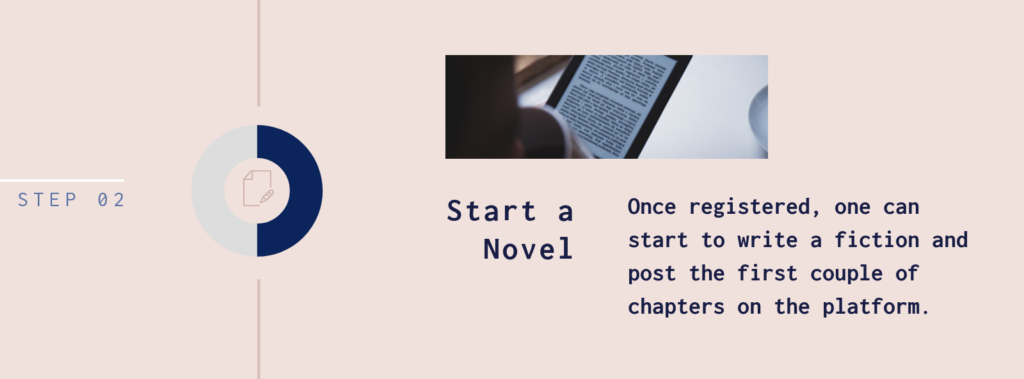

Network literature platforms proffer the convenience for one to become a writer. “You can publish everything as long as you’re a member of this website,” says Huanchu. “It is simple to sign up, usually you just need a phone number or an email address, then you can successfully create an account. Done.”

Yet the easy access is also an argument, which makes traditional literature query the quality of network literature works.

If everybody is eligible to post so-called ‘literary works’ online, surely the overall quality can’t be guaranteed.

Liting Zhang, an editor working in print publishing

Traditional writers are deeply concerned about creation freedom while online writers are busy with tailoring stories for the reader out there to sell.

“I think highly of creation freedom,” says Huiwen, who writes freelance. “I would rather not be disturbed at all while writing, let alone allow a full participation of readers.”

The straightforward communications between readers and writers may give an impression that editors don’t even have to exist in network literature, but they do.

In the publishing houses, editors “search for potential contents and reach out to writers proactively,” says Liting Zhang, and “usually personal preference is the prime rule” of her selection.

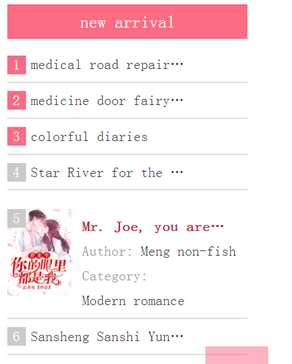

But the daily large outputs on network literature platforms don’t permit editors to work in the same way as traditional editors. So instead of aimlessly hunting, they wait and let readers decide.

“They wait for the good stuffs showing themselves,” says Huanchu. “When your number of subscriptions reaches a certain standard, they will come to you.”

Click rate and subscription that accurately show reader’s choice are network literature editors’ only criteria for market evaluation.

Being contacted by an editor can be the turning point of an online writer’s career, as it usually means this novel is qualified to be advertised on the front page of the website.

Huanchu still remembers clearly the triumph that followed her first time of being advertised, “the first day after I got recommended by the editor, the growth rate of subscriptions jumped from 200 per day to 2,000 per day.”

Here again, the story goes back to the reader. True competition begins where readers enter the frame. The low-cost conversations between writers and readers make network literature extremely sensitive to the market.

“At bottom is the market,” Liting, from a traditional editor’s eyes, contends. “The goal of network literature is to catch eyes and to satisfy readers’ curiosities.”

In a society that pursues efficiency, the direct communication between reader and writer within network literature saves much time, while “traditional literature undergoes more steps to enter the market,” says Liting.

The close reader-and-writer relationship is actually a social venue. Readers want more fun, and writers want a bigger attention. People network each other on consummate network literature webs for double-win reasons.

“I participate in the dialogues too, in the chatroom of my fans,” Huanchu takes the experience as unexpected bonus from network literature, “not only about the novels, but also something in daily life. I actually became quite close with a few of them, as friends.”

The age level of online readers in China nowadays helps explain how important this relationship is for network literature’s development.

According to the Network Literature Development Report, 2018, rejuvenation has become the main trend of the development of network literature in China. Z Generation, those who were born after 1995, is occupying the market. The number of Z Generation readers of network literature increased 20% within 2018. And one thing they seek particularly in network reading is an active interaction.

“There are some older readers for sure, but most of the people I know who read network literature are at my age,” says Wuxin. “I guess that’s partly because the young are more familiar with electronic devices, and we look for free expressions.”

The young keeps bringing more and more dynamics into Chinese network literature, like they are shouting: “Let the storm of be!”