In an age when information warfare, fake news, and Russian robots are manipulating us into the subversion of democracy, why are we so susceptible?

The year was 2019, and Mark had just become a stooge for a foreign government. Sitting on the couch, he had barely been watching the awkward reality underway on TV. With an air pod in one ear, playing his new album of the week, he could only half hear it anyway. The phone was out, Instagram up, and the thumb flicking a rapid scroll through pictures. Bored. A few easy movements and boom, Facebook.

Again, the page was on the move, whirling round like a never-ending toilet roll with new information to swipe. Until it stopped. What was this? “Nigel Farage supports the anti-vax movement.” Dislike that, he thought. And tapped. Angry face.

Should I share it and let others know? Obviously. And there, the news he felt important to him, was now with 762 Facebook friends, who might feel it too.

The fact that the headline was absolutely farcical didn’t register, he had read lots of posts about the politician recently and was enraged at the man. It was information he endorsed, highlighted, and told almost everyone he knew.

With everything else he was listening to, watching, reading, liking, sharing, messaging and posting, he didn’t really give it a second thought. Let alone his dinner on his lap, or the other people in the room. And so, his unwitting participation in international espionage had begun.

In a life lived increasingly online, this scenario isn’t miles away from reality for many of us. As in the case of Mark, it is the sheer bombardment of ‘stimuli,’ as psychologists would call it, that causes problems for our brains, and subsequently affects our decision-making ability.

Dr Max Blumberg, research psychologist at Goldsmiths University of London, explains that in the modern era, our brains often lack the availability for in-depth analysis.

“In an age of informational overload, you just don’t have time to do that kind of processing,” Max says. “If you want to fool people, all you got to do is do it while their brains are full.”

The grounding theory for what Max calls a ‘full’ brain, is based on what experts refer to as your working memory, a feature of cognitive anatomy situated in the cortex, the part of your brain that makes decisions for you. However, the limit of the working memory is that it only has about seven slots.

This many does allow the brain to do a number of things at once, say, drink a coffee, chat to your Mum on the phone, and keep an eye on the football game, but when one of those activities starts to require real concentration it will need to use two or three of the slots at the same time, and something else will have to stop. Herein lies the problem for our online life.

“So now technology has evolved, there’s a lot more information coming at you but you’ve still only got seven slots in the brain,” Max explains. “The brain hasn’t kept up with technology, it evolved over 2 million years, seven slots was more than enough to see a sabre toothed tiger coming round the corner, that your friends are safe, that’s what our brains were evolved for, that low level of stimuli, so they’re not evolved for the high levels of stimuli we have today basically.”

This evolutionary misalignment, of technology and psychology, becomes more serious in an era of fake news. The threat from non-state actors has been well documented, and as elections for the European parliament take place this week, analysis by online security firm SafeGuard Cyber has found that around half of all Europeans have been targeted by disinformation linked to Russian social media accounts.

Information overload plays into the hand of information operations such as this, as we become more pliable to alternative truths, external agendas, and having our emotions pressed and needled until they flare up. This vulnerability comes not only from a cluttered and busy mind but, as a result, from our diminished critical faculties and favoring of quick intuitive thinking to get us through the day.

Take this scenario for example. A political advert on Facebook states the following: “What does EU open borders and undocumented migration mean to you?” Underneath this bold headline is a picture showing crowds and police gathered in Paris during the wake of the 2015 terrorist attacks.

In his book ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman describes how we think – by means of System 1 and System 2, either fast or slow. The distinction explores how we interpret the world, with intuition, or deliberation, and is particularly important in explaining how we react when faced with adverts similar to the example above.

Cognitive biases, described as effective as optical illusions, govern our thoughts much more than we notice. Intuition often acts as a mental shortcut and is to blame for many instances of human irrationality. In the advert, what Kahneman defines as the availability heuristic, can lead a reader to be misled and to link migration and terrorism because that is the only information available to them. This is just one bias out of the many our brains can unconsciously fall prey to when thinking quickly.

In the current political climate such glancing interpretations are dangerous, but as Dr Blumberg highlights, they are increasingly likely. “Let’s assume that you need three or four slots to do Kahneman’s slow processing, how often does one have four slots free nowadays?” He says. “We know about the bot factories, so if they’re sophisticated enough to do that…”

“Psychological warfare is taking away people’s ability to do critical thinking, and of course, that’s the last thing they want you to do, is to have enough brains to be able to question that kind of thing. And so, it’s a great weapon overloading people because you take away their critical faculties.”

Internet psychologist Graham Jones, an expert in online use and behavior, points to how such online tricks are not reserved to bots, or foreign intelligence services. “We are being tricked a great deal online,” he says. “People believe things which have no basis in fact.”

“People have fallen into believing that what Google serves up must be true, but Google makes no checks regarding the accuracy of what they deliver. Furthermore, on services like Facebook, the algorithm presents information in an order that makes the user think it is important when it might not be. On top of all this, advertisers use techniques to make people think and behave in certain ways.”

It is a vulnerability that has intensified further in an age where information and psychological warfare has not only gone online, but has become increasingly personal.

Since the revelations surrounding Cambridge Analytica were released in early 2018, we have become frighteningly aware of how our data, that has been collected online, can then be used to target us specifically, in a unique, and tailored way.

What was previously above the line commercial advertising – the same ad broadcast to everyone watching the Saturday night movie on Channel 4 – is now individually designed for you, and coming at you straight through your phone.

The political pamphlets dropped en masse in WWII – such as those written by Sherlock Holmes novelist Arthur Conan Doyle – are now meticulously curated messages, hitting you with pinpoint accuracy on Facebook, You Tube, and Instagram.

In reaction to the Trump election and Brexit vote, such segmented targeting has led to much debate and opposition, but Dr Blumberg questions the logic of such criticism. “We’ve been targeting people to buy products commercially for years, why is it suddenly illegal to use it in politics?” He says. “What makes it illegal to target groups of people with messages?”

“It’s ok to make an advert that goes to the whole nation with a nodding dog in the back window of a car because it’s going to millions of people, but it’s not ok to take one of a particular type of dog that you know people like and use that because it’s too small a group?”

Countering such an array of issues, and stimuli, online, it is a challenge to be conscious of where it has come from and by who. Recent efforts by social media platforms are a step in the right direction, such as addressing who political adverts are from or banning groups that perpetuate hate and racist content. However, the need for critical thought remains of paramount importance in the fortification of a barrier to manipulation.

The point was underlined by Kahneman in 2018, when he sat down for the podcast ‘Conversations with Tyler,’ and he had the following advice. “There is one thing we know that improves the quality of judgement, I think, and this is to delay intuition.”

.

.

.

See below gallery for a history of information warfare.

Credit & thanks to www.psywar.org

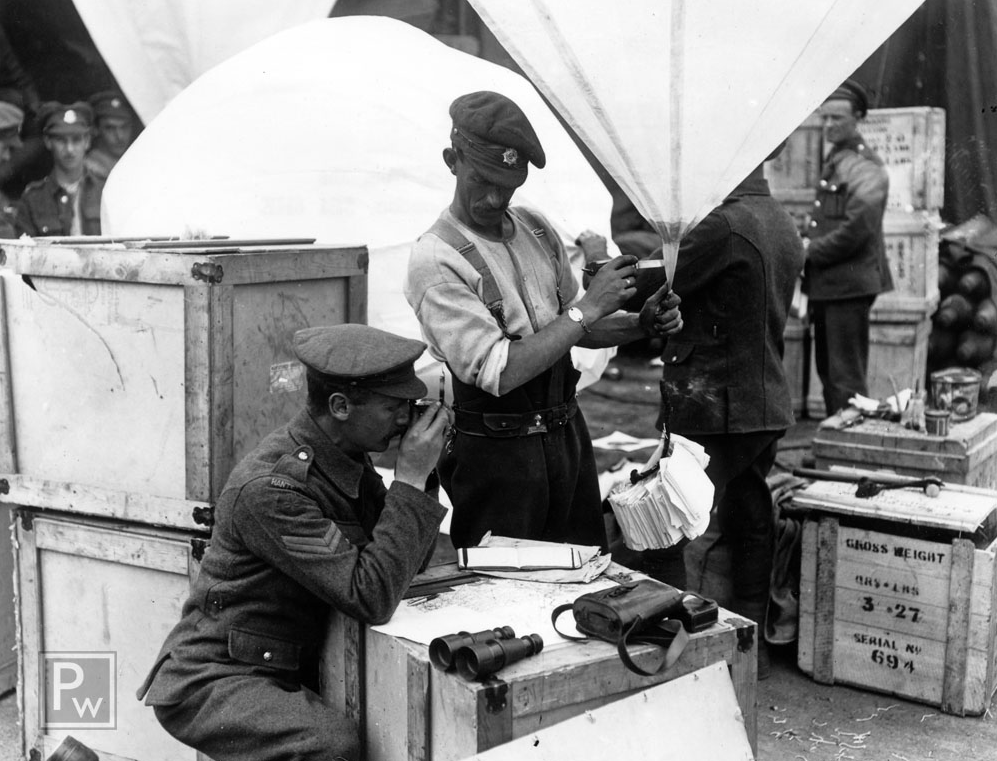

WWI British balloon distribution of propaganda leaflets.

Men of the Hampshire Regiment attaching leaflets to a balloon, near Bethune, France.

WWII RAF distributing propaganda leaflets through the flare chute of a Whitley bomber.

WWII RAF loading leaflets into the Whitley aircraft.

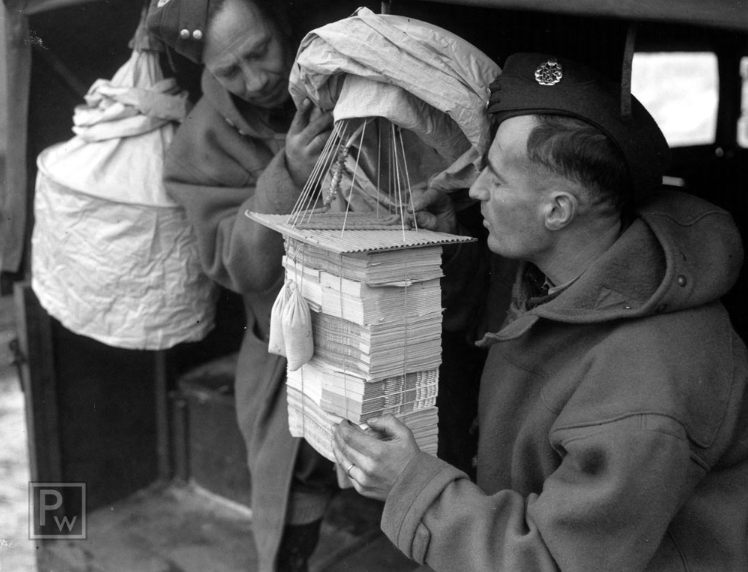

WWII The “M” Balloon Unit, each balloon is inflated its appropriate load is made ready.

Inflating balloons from hydrogen cylinders.

A soldier of the Psychological Warfare Division attached to the U.S. Army holds a loudspeaker in the window of a factory to beam a surrender ultimatum at the enemy a short distance away.

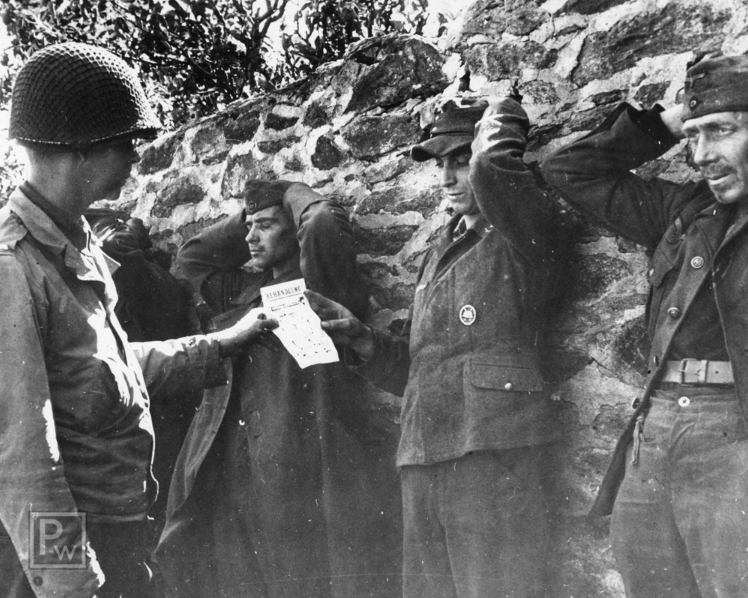

WWII Psychological warfare leaflet persuades Nazis to surrender.

KOREAN WAR

Loading a cluster adapter in Yokohama, Japan. The bomb type will contain 22,500 psychological warfare leaflets.

350th Psychological Warfare Company. A Loudspeaker team training at Fort Bragg.

VIETNAM

Side view of a Special Operations Squadron dropping leaflets over the Republic of Vietnam.

Fixed wing aircraft used in the distribution of leaflets and loudspeaker appeals.

OPERATION RESTORE HOPE

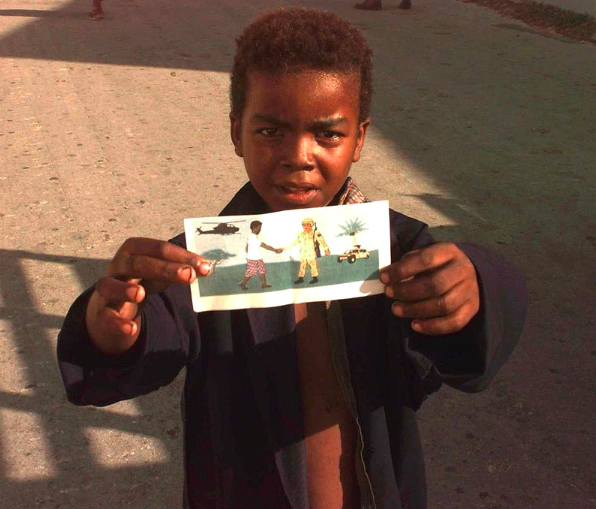

A young Somali boy holding one of the PSYOPS leaflets up to the camera.

US Army, Corporal hands out DC comic books to children at a refugee camp in Boznia-Herzegovina.

US Military personnel assigned to the 4th Psychological Operations Group.

KOSOVO

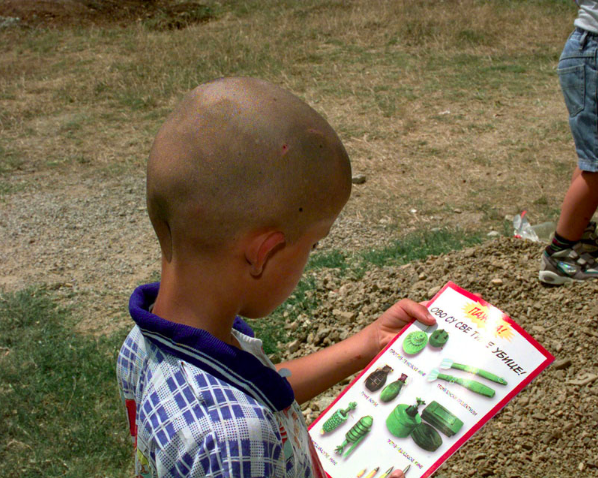

A young Serbian boy reads a comic book about mine awareness.

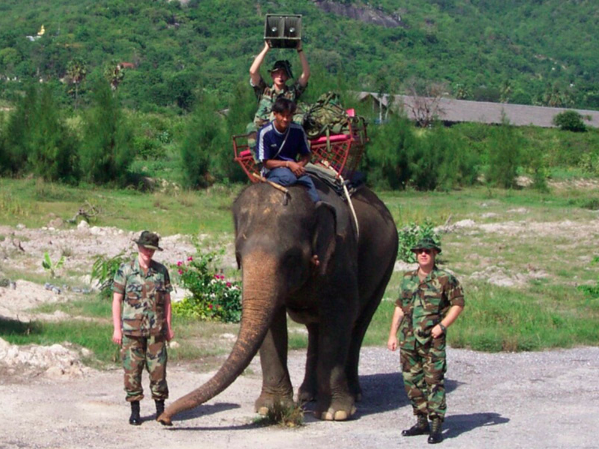

During Cobra Gold ’03 in Thailand, PSYOP personnel make use of local transport for a mobile loud speaker operation.

Maj. Bill Gormley hangs posters in Afghanistan, letting people know that schools are reopening,.

Information Operations releases a box of leaflets at a drop in Afghanistan.

10,000 warning leaflets dropped over Afghanistan to communicate with Taliban extremists.

Southern Afghanistan, leaflets were dropped in support of operations to defeat insurgency influence.

Coalition forces release informational leaflets out of a UH-60 Black Hawk.

A boy holds a flyer about the upcoming Iraqi elections.

350th Tactical Psychological Operations conduct a leaflet drop.