Music and language go hand-in-hand, and on the Isle of Man the two are all but inseparable as language activists combine language revitalisation efforts with song and dance, so why is it important to the Manx language that music continues to be an essential part of the revival culture?

A gaggle of five- and six-year-olds orderly file into the classroom, and not-so-orderly put up their coats and find a seat on the floor, wiggling so much it’s hard to believe they just came in from playing outside.

“Who remembers how to say good afternoon in Manx?” asks Dr Chloe Woolley, when at last the volume has lowered enough to make herself heard. Some of the wriggles stop, while others try to make their voices heard, maniacally waving their hands over their heads.

“Fastyr mie,” one little blonde girl proudly announces, only to have her answer echoed by her fellow students. Though they don’t speak Manx regularly, once a week, during their music lessons with Woolley, Manx Gaelic becomes the lingua franca.

“How could we show we’re how going to the door?” asks Dr Chloe Woolley. A couple minutes later, the fifteen Form 1 and 2 students have decided on pointing in front of them and pretending to open a door.

Then, with an accordion accompanying them, and a lot of giggles, the children sing Traa dy gholl dy valley, “Glad to go home after school.”

Teaching lessons like these is one of Woolley’s favourite parts of her job. As the Manx Music Development Officer at Culture Vannin, one of Woolley’s responsibilities is to work with schools to develop resources for the introduction of Manx music in the classroom.

“I think it’s nice working with children in that space,” says Woolley. “See where the future is bright and they just absorb what you’re telling them.”

Trying to wrangle 15 five and six-year-olds right after recess may not sound like an ideal time to introduce a new language, but bring in a whistle and a fun song, and they join right in.

When prompted to remember how to say “good afternoon” or how to say “goodbye,” the students were all too eager to share their newfound knowledge, and as Woolley packed up, they were still singing and dancing.

Once they leave, though, most will not hear Manx again until the next music lesson, as the language that was once spoken across the island is now spoken by only 1,823 people as their second language, according to the 2011 census.

Woolley is the Manx Music Development Officer at Culture Vannin, a charity dedicated to the revitalisation of Manx language and culture. Part of her job is to engage with the community through music, such as the weekly music classes she does in St John’s English-medium primary school, as well as through youth music groups sponsored through Culture Vannin.

“People sort of dismiss Manx music and the language,” says Woolley. “It’s like, oh, it’s just a hobby, you know, or, it’s nice, if you have the time to do that kind of thing.”

After the death of the last native Manx speaker in 1974, the language was pushed to the side in favour of the dominance of English, with children being taught that their language was backwards, a sign of poor education. Even today, with the recent revitalisation of much of Manx tradition, there are still people, particularly older members of the community, who push back against the language.

“I think, historically, if we’re talking about the 1970s and 80s, it [Manx] was often seen as a sort of badge of cultural identity to people,” says Annie Kissack, the current Manx Bard. “We would expect to hear it, going to the right house and sit around and be part of that group.”

However, the language was already in steep decline, and over the next decade or so would drop into obscurity, only heard in some of the more remote parts of the island.

Kissack began singing Manx songs under the legendary Mona Douglas, one of the prominent collectors of Manx folklore and culture in the 1980s. While Kissack did not grow up speaking Manx outside of choir classes with Douglas, she credits those classes with spurring her on to learning more about Manx language and culture.

“By the time I arrived in the mid-60s, late 60s, Manx had been gone a very long time and there weren’t many children generally interested at that point,” says Kissack. Her interest in music and the language eventually took her from Saturday-night choir lessons with Douglas to where she is now, a teacher at the Manx-medium school, the Buscoill Ghaelgagh, as well as the director of the choral group Caarjyn Cooidjagh.

Kissack and her songwriting partner, Aalin Clague – who directs the Manx band Clash Vooar – work together to uncover old songs or parts of verse that have yet to be put to music. By parsing together old texts and bringing it into the choir or the band, they are shedding light on old traditions as well as introducing more people to music.

“There was a time when people didn’t want to even acknowledge they were Manx, and anything to do with that,” says Kissack. While Kissack remembers going to homes where Manx was spoken, others remember the use of the language outside of the home being discouraged, to the point that if someone was heard speaking the language, they would face retaliation by those around them.

Phil Gawne, the director of Moojiner Veggy, raised his now-grown children with the language, but remembers all too well the reactions he would get when his family would speak Manx in public.

“You know, in the 70s and 80s, people were getting thrown out of pubs for speaking Manx,” says Gawne. He recalls how even Manx music was banned from public places until the efforts of individuals like Douglas in the 80s and 90s helped to portray Manx in a different light.

Upon finishing her university degrees, Kissack returned to the Island and was part of some of the early revival efforts, especially concerning choral music. As most of the first songs to become popularised were pub songs, perhaps because of the simple tunes and words, Kissack was looking for something more with re-introducing Manx music to others.

“I suppose, the last 30 years or so I’ve gone through as far as I can all the traditional songs that might benefit from being performed in the choral sort of way to some extent or another,” Kissack says. “Some things that would never be heard otherwise might be heard in a different way.”

In the last 20 years, give or take, the Manx music scene has grown quickly, from soloists to groups, bringing in talent from beyond the isle while at the same time maintaining close ties to its Manx origins. Most of the individuals associated with Culture Vannin and other Manx organisations see music as a major element of getting people involved in learning more about the language.

“I suppose the music is open, perhaps to more people,” says Kissack. “I know that our audience will like that kind of music…and then they might suddenly [be] interested in Manx.”

There are multiple Manx musical groups on the island, with opportunities for everything from singing in a choir to dancing and playing instruments, no matter how old you are.

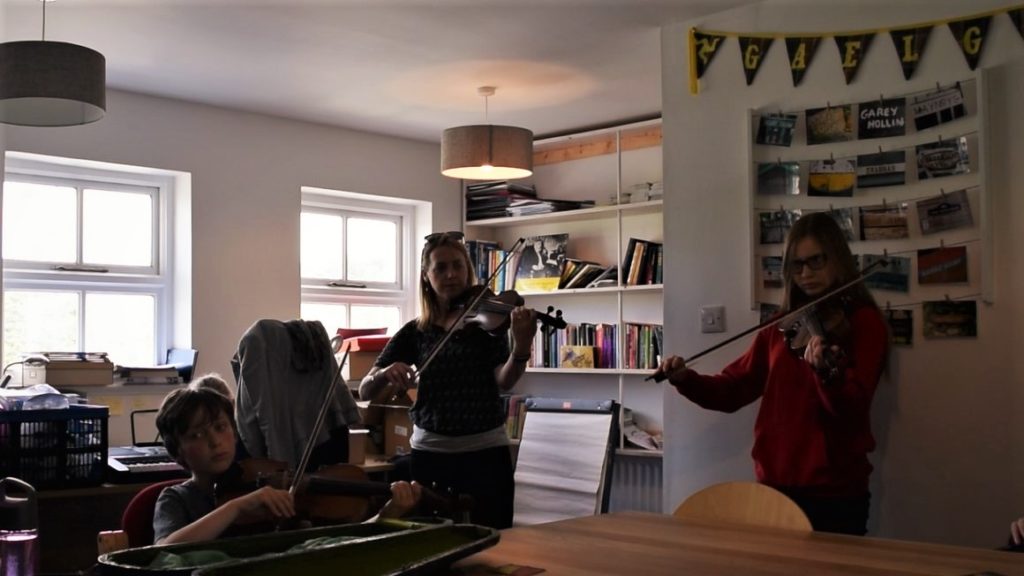

The main adult groups are the choir Caarjyn Cooidjagh, as well as the band Clash Vooar, but there are also two youth-specific groups. Both groups are sponsored by Culture Vannin, which provides rehearsal space for them, and Woolley directs the younger group, Bree, which rehearses once a week on Saturdays in the same room that serves as an office to the Yn Greinnyder, the Manx Language Development Officer.

Surrounded by Manx language success stories, the young musicians make room for their music books between pins that read “I heart Manx Culture” and papers with Manx lessons. Bree is for individuals who are new to playing instruments or want an introduction to Manx music, and cover an assortment of instruments from guitars to fiddles to pianos, and, of course, a couple of singers.

The other group, Scran, has recently received international recognition for their music, performing at a couple of Celtic Festivals in Scotland and recording a CD. Most are former members of Bree, and the main qualification to be a part of Scran is to be able to play music by ear, the way it was traditionally taught on the island.

Paul Rogers, an Isle of Man transplant from Wales, works with Scran and understands the importance of preserving indigenous languages. He studied both Welsh and Manx in university and firmly believes the importance of using indigenous languages where they are found.

“So for example, in Scran, I use a lot of Manx in this group because a lot of them speak Manx, but some of them don’t,” says Rogers. “We’ve decided that Max is generally the language in here. So I speak a lot of Manx, but I do make sure the one, there’s a few that don’t speak Manx, so to make sure that they are understanding, we sometimes use the English name. But I’d rather have a group where I didn’t need to use any English so I could just use Manx and the children could come and just use Manx.”

Most of the time Scran plays a mix of traditional Manx songs, both arrangements already done or their own take on a piece, but they do like to have fun from time to time.

“Last year, they took some more modern songs and made their own arrangement, just for the fun of it,” says Woolley.

Many of the young musicians are multi-talented, often performing songs and then changing for dances at various Manx gatherings around the island. The groups are voluntary, so while their parents might be encouraging them, in the end, it is up to the young people to stay involved.

“Music creates an environment where Manx is the primary language,” says Rogers. “Other than that, it’s just a hobby.”

Even though it may be ‘just a hobby,’ the integration of Manx into day-to-day life through pastimes means it is getting into the facets of everyday life for those involved. In conjunction with school-based language programs, the implementation of programs like Scran and Bree allows children and young adults to have a space to practice Manx outside the classroom, helping to make it more of an integral part of their culture in all aspects of island life.

Between regular lessons in school, and the celebrations of Manx history and culture at events like Tynwald Day and other key Manx calendar holidays, music provides a gateway into the language, making it more accessible for those who want to learn, and giving those who do know it already the chance to further their knowledge.

Clague, who began learning Manx as a child, but began studying Manx in earnest when her child began studying at the Buscoill Ghaelgagh, sees music as an essential part of the language revitalisation process.

“I think music is a brilliant vehicle for transporting ideas and words and sentiments and atmospheres,” says Clague. “I don’t get too hung up about authenticity in terms of a flame that’s been passed…I think that it’s just kind of a vehicle to move ideas around.”