The Extinction Rebellion movement has taken the UK, Europe and much of the world by storm – engaging millions in the climate crisis. But some environmental justice activists have raised concerns over the tactics of the organisation. Faith Rhiannon Clarke speaks to members, observers, and those trying to change the organisation from within…

Hussein Said didn’t have a particularly political upbringing, apart from finding out his welsh miner grandfather once scrawled Trotsky on the side of the family’s garden shed, he tells me, beaming at the thought.

But having been born in Baghdad, Iraq – one of the most war-torn, invaded and occupied countries of the twenty-first century – was always going to have some influence. Growing up in the UK – a country which was part of the coalition to invade his birthplace – eventually pushed Hussein into what he vaguely describes as being “that area of politics.”

Not only this – but being a person of colour living in Danescourt – an area of Cardiff with a 91.6% white population – was at times alienating.

“I grew up with a lot of white people around me,” Hussein explains. “When you’re not white, you’re constantly told that you’re not the same, and you start thinking about who you are.

And then you find – I don’t know – solidarity, I guess, in people like Noam Chomsky and Malcolm X and Che Guevara – saying things supporting your view.”

After completing his A-levels, Hussein went on to study Law at university, and eventually became a human rights lawyer, working first with the LGBTQ+ community in London and now at Asylum Justice in Butetown.

But while Hussein was doing “the best he [could] through his work” – he still felt it wasn’t enough.

“Just helping an asylum seeker here and a trans person there is not necessarily showing solidarity with those people,” he tells me. “You know, they’re not just people you help through the law, they’re real people – we should always try and show solidarity as best as we can.”

Hussein’s work with asylum seekers not only pushed him into anti-racism activism, but also made him realise the links between climate change, conflict, oppression and race – and the importance of intersectionality in activism.

“Nobody makes the connection between war and climate too often,” says Hussein. “Growing up and realising that fossil fuels and oil were the reason why Iraq was invaded – you make those connections.”

“Syria, Afghanistan…you know, they never make those connections for you, because they don’t want you to know. People always say, ‘well, it sounds like a conspiracy.’ It’s not a conspiracy, it’s just how the world is run.”

People always say, ‘well, it sounds like a conspiracy.’ It’s not a conspiracy, it’s just how the world is run.

As Hussein tells me this, he’s laughing in an ironic way, his eyebrows knitted together in confusion over the idea that so many people fail to see what he sees. To him, it was personal.

Last year, Hussein joined Extinction Rebellion (also known as XR) – an organisation that has gathered momentum not only throughout the UK and much of northern Europe, but in the US, India, South Africa, and even the Solomon Islands. But Hussein didn’t necessarily join because the group inspired him to act – he’d been thinking and talking about climate change for years before – rather, he joined because he couldn’t stand by and watch a largely white and middle-class movement fail to engage the very people at the forefront of environmental issues.

“Our home is on fire”

In order to draw attention to the urgency of climate change, XR use non-violent civil disobedience – blocking roads and bringing public transport to a standstill – and aiming to get as many people arrested as possible.

It’s a sunny day in July, and XR activists are blocking roads in various parts of the UK. In Cardiff, the main bus and taxi route has been cordoned off, and a lime green boat sits in the centre of Castle Street. Some activists have chained themselves to the boat, while others are singing and dancing around it. A group of observers have congregated: cautious, but clearly taken by the cause.

While some people are unable to get to work, others have taken time off work especially to be here.

XR activist Louis Whelan, a 25-year-old data analyst, says the group act “to stop the collapse of human civilisation and deterioration of life on Earth.”

It sounds dramatic, but he is not alone in this viewpoint. Many XR activists signed up to the movement after the release of a report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which predicted that we have only twelve years to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius. Anything above this, the report warned, would see catastrophic consequences of widespread super droughts, extreme flooding and an increase in freak weather events.

While many XR activists talk about how we will all suffer in the future – with 16-year-old activist Greta Thunberg stating that “our home is on fire” – critics such as Wretched of the Earth have argued that referring to the earth as one home overlooks the nuances and specifics of climate change and environmental inequality which can presently be mapped by a north-south divide.

While climate change will affect all of us in some way either now or in the future, the impacts will not be felt all at once, and will vary in intensity.

So does that mean a country just disappears…no longer exists…?

According to Dr Jen Iris Allen, of Cardiff University’s School of International Relations and Politics, those who are currently struggling, are going to struggle increasingly more as conditions worsen.

“Everybody is going to feel this in one way or another,” she tells me as we sit in her office.

“[But] the people who will be affected more slowly and more indirectly, will be those who are rich.”

On the frontlines of climate change are the world’s poorest nations. With sea levels rising, and expected to rise between 10 and 32 inches – low-lying countries such as Bangladesh, already prone to flooding, can see up to one-fifth of the country flooded at once during the rainy season. Bangkok, Thailand, could see 40% of the capital city submerged by 2030, while Manilla, Philippines, is subsiding at a rate of 10cm per year.

Meanwhile, the pacific island of Tuvalu is expected to disappear altogether. When you take the time to think about that – a whole country and culture gone – it’s hard to swallow.

“It’ll probably disappear at 1.5 degrees,” says Dr Allen. “We have no way of avoiding that right now. So does that mean a country just disappears…no longer exists…? Or do we relocate people and say, ‘Here, you can have this piece of land now, sorry about that’?”

Drought is also seizing many countries already prone to hot, dusty conditions – from Somalia, to India, to Afghanistan. With drought comes the failure of crops and as a result, food insecurity, water shortages and even conflict – Mali and Sudan are examples of this – with political scientists suggesting that climate change could be driving conflict, particularly in countries where tribes rule different territories and disputes have erupted over land and resources.

Famine and conflict will also result in climate refugees – a term unheard of maybe ten or twenty years ago. While it’s extremely difficult to predict the scale of climate-induced immigration, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) estimates that almost two-thirds of internal displacement in 2018 (17.2 million people) was triggered by natural disasters such as extreme weather, earthquakes and cyclones, and this number is only expected to rise as precipitation patterns change and freak weather events become more frequent.

Hussein, who is working with refugees and asylum seekers every day in Cardiff, notes that while XR are quite long-sighted in their goals to prevent climate catastrophe in the future, they are short-sighted in that they fail to link many of their demands to the impacts of climate change happening right now.

“Every single day in the global south and in countries that have no water, people are literally stranded…they try and travel [across] the Mediterranean… and they’re dying,” says Hussein desperately.

“We should link direct action to: what are you doing about climate refugees, you know?”

“Racist climate crisis”

But while the impact of climate change is yet to fully affect the UK, environmental justice groups have drawn attention to the impact of environmental issues on black and minority ethnic communities in Britain.

Back in 2016, when Black Lives Matter blocked London City Airport in protest, claiming that “Black people are the first to die, not the first to fly, in this racist climate crisis” – they drew attention to the impact of air pollution, which disproportionately affects black and minority ethnic communities in London. The group also pointed out that while air travel simply isn’t affordable for many people of colour and deprived communities in the UK, the government is happy to deport asylum seekers back to their home countries which are often torn by conflict, famine and food insecurity, often driven by – ironically – climate change.

The link between environmental issues and race was first made by Dr Benjamin Chavis in his 1987 ground-mark study “Toxic Waste and Race” – widely associated with coining the notion of “Environmental Racism.”

Chavis’ study identified that race was the single biggest variable in relation to the locations of hazardous waste facilities across the US, but he also made another important observation: he suggested that because black and minority ethnic communities are exposed to an array of issues – such as poor housing and education, unemployment and poverty – they “cannot afford the luxury of being primarily concerned about the quality of their environment when confronted by a plethora of pressing problems related to their day-to-day survival.”

The timescale of climate change means different things to different people. For some, it has already seized their home, land and crops; for others, it is far-off and abstract, hardly a priority when they’re trying to find money for their next meal, or for a bill that they have to pay tomorrow.

For ethnic minorities every day is a struggle. If you’re a woman, if you’re black or brown, if you’re a different religion, if you’re gay or trans…it’s a system that doesn’t really want you

Isn’t twelve years a long time for somebody facing more imminent worries? I ask XR activist Louis.

He acknowledges this – “People who can barely make it to the end of the week aren’t thinking about the end of the world,” he agrees.

However, he still believes that direct action is necessary to prevent more suffering in the long-run.

“We understand that this is a huge inconvenience and it’s a symptom of the grotesquely unequal society that we live in,” says Louis.

“Those worst affected will be the people struggling the most already – people trying to reach a universal credit appointment or make it to the hospital. But if we do nothing then those people’s lives will get much, much worse.”

But Hussein believes that many XR activists “[don’t] really get the idea of struggle.”

“I think a lot of them haven’t been involved in [it],” he says frankly. “For ethnic minorities every day is a struggle. If you’re a woman, if you’re black or brown, if you’re a different religion, if you’re gay or trans…it’s a system that doesn’t really want you.”

“I’m against the state every day”

Observe any XR meeting or demonstration, and it’s difficult not to notice that it attracts a particular type of person – largely white, middle-class professionals, or retirees.

Academics suggest that the middle classes are most likely to protest because the working class and poor are more pessimistic, while the upper classes have more to lose. It has also been noted that retirees are often found in activist groups as they have more time to spare.

Those most impacted by climate change and environmental racism are seemingly absent.

One reason for this – which has been raised by environmental justice groups such as Wretched of the Earth – is XR’s tactics. XR encourages protesters to get themselves arrested in order to draw attention to the urgency of climate change. Back in April, over 1000 activists were arrested at XR protests in London.

But who can afford to “offer” themselves up for arrest?

Mainly people who don’t have a duty of care or a precarious job they have to hold-down.

Sian Vaughan, a retired head teacher, is one activist willing to be arrested: “It is relatively easy for me to put myself at risk of arrest,” she says. “I am not reliant on work and I have no dependent children.”

Hussein on the other hand describes civil disobedience as a “massive soft barrier to a lot of ethnic minorities.

“It’s just absolutely destructive,” he argues. “You can’t really have a movement based on civil disobedience if you want to engage people who are black minority ethnic.”

But according to the XR website, nonviolent civil disobedience is “necessary” to demand government action on climate change.

Dr Allen suggests that XR may see this as a last resort after years of peaceful protest, petition-signing and government lobbying has achieved only incremental climate policy in the shape of conferences such as the Paris Agreement – which have failed to bring about the radical environmental change that is clearly needed.

However, she also notes that “only a certain segment of society” can participate in civil disobedience, regardless of how nonviolent it may be.

“I’m a white immigrant to this country [and] I can’t get arrested,” she tells me, referring to her Canadian nationality.

“That’s even with all of my white privilege that I couldn’t do that. So if you’re a minority, if you’re even someone who just can’t lose two days of work because you’re in jail, or you’re a woman who has children – you can’t not feed your kids for two days because you’re in jail.”

Hussein says he only participates in XR civil disobedience when he knows there’s a low risk of being arrested.

I know that if they found something on my phone that is against the government, it’d be seen as much more serious – because of where I’m from, and also because of the work I do. I’m against the state every day.

“It’s just – I know that I’d be treated much differently,” Hussein tells me over coffee during his lunch break one Wednesday afternoon.

“I know that if they found something on my phone that is against the government, it’d be seen as much more serious – because of where I’m from, and also because of the work I do. I’m against the state every day.”

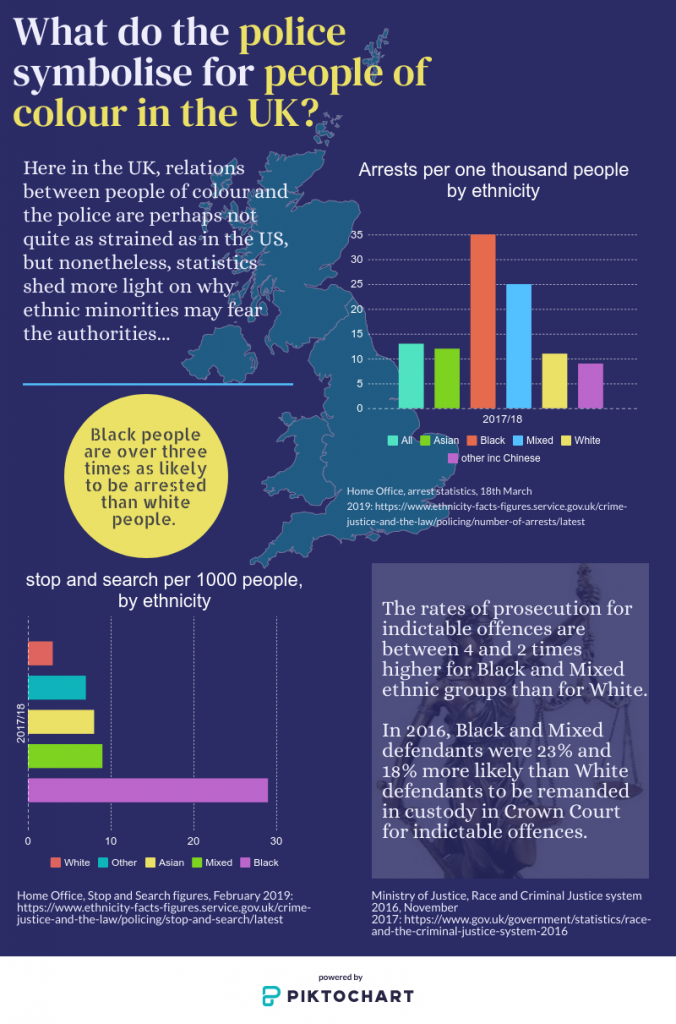

On XR’s website, the organisation states that it “[has] made a strategic decision to communicate with the police” in hope of increasing the chances of protests running successfully, however, Hussein says that most of XR fail to realise what the police symbolise for people of colour.

Government figures indicate that black people are “over three times as likely” to be arrested than white people.

At XR’s summer rebellion in Cardiff, Hugo, who has participated in XR since its birth last year, recognises that people of colour are more vulnerable to arrest.

“I witnessed it myself in the London one [protest],” Hugo admits. “They arrested the minorities well before they arrested anyone else.”

For Hussein, who is trying desperately to change some of XR’s tactics from within, he says the group focuses far too much on maintaining a positive relationship with the police, which loses them support from activists of colour.

“At the end of the uprising, they were thanking the police,” Hussein tells me. “I said, we don’t have to be against the police, we don’t have to shout and run up to the police and hit the police…but we should be showing solidarity with those who are oppressed by the police, rather than thanking the police.”

There has also been criticism of a “prison guide” that XR published and then removed, which included pointers such as “bring plenty of good literature” and “if you get solitary there’s plenty of time for meditation”, as well as tips including sticking to a vegan diet and practicing yoga.

The guide was criticised for a lack of realism: in England and Wales, prison assaults are at a record high, increasing by 20% in the year running up to September 2018 to a total of 33,803 assaults, and this is without noting the 92 self-inflicted deaths in prisons during 2018.

Yet it is clear that the civil disobedience and arrest aspects of Extinction Rebellion have drawn the most attention from media outlets – which plays an essential role in spreading the group’s message and recruiting new members.

But according to the XR website, “we don’t want or need everyone to get arrested.”

Sian agrees – “There is a big message that you can support XR in lots of ways and only a minority of us need to be arrestable,” she says.

One point that has been raised by many XR activists is that those who can afford to should use their privilege to risk arrest. Many retirees in particular feel this way, arguing that they should put themselves forward to fight for the futures of their children, or grandchildren.

While Hugo says he agrees that these tactics are not accessible to everyone, he also feels something of a duty to use his own privilege to risk arrest. “We are doing this on behalf of minorities,” he says. “We realise if we don’t do this the people in the Pacific, the people all around that area are really screwed.”

While Hugo clearly has good intentions, this comment does seem to overlook the activist efforts of people in regions such as the Pacific islands. Thousands of Pacific Islanders have joined the recent climate strikes. On the island of Kiribati, children rallied and cried “we are not sinking, we are fighting.”

“It harkens back to this idea that there’s no agency in black and brown people,” Hussein says. “I think being arrested is just [about] martyrdom, this idea that you just need to sort of sacrifice yourself for the greater good.”

When I ask one XR member, Steve Poretta, whether there is a diversity issue in the Cardiff branch of XR, he says he can’t be sure without a survey, though to me it seemed clear after glancing around the crowds during their “Summer Rebellion” and seeing only a handful of activists of colour.

Steve says that “[he] would rather have the most powerful groups represented in XR than the weakest.

“There are far too few people like me involved,” he says. “They are too busy on one of their ten foreign trips a year, or on their boat or just living a very comfortable life…”

Steve explains to me that he retired as Head of Capital Projects for Tata Steel back in 2016, hinting that he earned a high salary and subsequently enjoys a comfortable life. He is now working on a strategy where he hopes to access individuals within professional institutions to convince them to divest from fossil fuels.

Steve is right in suggesting the rich need to be held to account; but how do we define power? Is power capital, or people?

Perhaps the middle and upper-classes have more power to make a difference through divestment of fossil fuels, or cutting out air travel (because they might use it more) – but in terms of people power, the most successful – or significant – movements in history have been led by the working classes, marginalised communities and people of colour: the civil rights movement, anti-apartheid, Miner’s Strike, and the LGBT movements, to name just a few.

it’s not about XR being about that, it’s about XR just showing solidarity with it – having that within its principles.

In a bid to create a wider and stronger movement, Hussein has tried relentlessly to encourage XR to show solidarity with other campaigns such as Stand Up to Racism, as he believes the intersection at which the environmental meets the social has to be underlined.

However, he has been met with little support, as some members do not see this as XR’s responsibility.

“[You] can’t be single issue movement,” insists Hussein. “This idea, that they say ‘oh but XR aren’t about that’, it’s not about XR being about that, it’s about XR just showing solidarity with it – having that within its principles.”

Hussein also points out that Martin Luther King and other civil rights activists would talk about the plight of the global south, the Vietnamese war and Palestine-Israel conflict. They used the civil rights cause not just to highlight inequalities in the US, but to criticise imperialism and structural racism the world over.

XR’s reluctance to engage with other organisations seems to stem from the ten principles that they recommend members follow – one such rule states that “[members should] avoid blaming and shaming.” As a result, the group steers clear of party-politics, which means not making statements against politicians or showing up to demonstrations that target certain politicians, even in the name of anti-fascism and anti-racism.

This explains the criticism Hussein has been met with when posting within the XR online community about attending anti-Trump demonstrations – in some instances even having his posts removed.

XR also remains neutral in an attempt to gather support from both ends of the political spectrum, with the hope of uniting people of the left and right in a fight against climate change, using the argument that Conservatives should get involved because their property and capital is at future risk – along with human life.

But is there a difference between being “party-political” and merely having a set of moral messages that you stick to? Surely an organisation that stands for climate justice should also stand for equality – in every sense?

For Dr Allen, the decision of whether you stick to one message and strategy and risk alienating people, or you broaden both your base of people, and the issues you are fighting, is a difficult one.

“A movement can’t be about everything,” she admits. “But that’s hard – because intersectionality really matters.

“[but intersectionality] is very nuanced and hard to communicate – it’s got to fit on a banner, or you’re in big trouble, right?”

We [should] stand up to that – whether it’s Boris Johnson doing it, whether it’s Trump doing it, or whether it’s Saudi Arabia doing it.

But for Hussein, opting not to have a clear political stance in hope of appealing to everyone is part of the problem. While XR say that one of their ten principles is “to welcome everyone,” they subconsciously close themselves off to many people of colour and low-income groups who have strong views about the elite ruling class in the UK. Hussein argues that by not denouncing the very people who are to blame for marginalising these groups, XR are in danger of marginalising them further.

“That’s not how you’re going to involve ethnic minorities – when you start talking about going against Trump, going against Boris being too political,” says Hussein. “You know, completely showing no solidarity with the most oppressed groups in society.”

“Climate change is about the oppression of minorities and people of colour all over the world,” he adds. “We [should] stand up to that – whether it’s Boris Johnson doing it, whether it’s Trump doing it, or whether it’s Saudi Arabia doing it.”

But Dr Allen also notes that there are some “disincentives” to groups covering multiple issues or joining forces with other organisations. There is a chance that certain voices will be heard more than others, or that the groups doing the grassroots work on racial inequality or gender inequality won’t get the attention they deserve.

When voices aren’t being listened to, “[movements] fracture immediately,” she says.

But Hussein argues that XR doesn’t necessarily need to parade these messages themselves or collaborate with other organisations, but simply show solidarity with anti-racist groups – whether through attending and promoting other demonstrations, releasing statements on social media or simply including strong messages in their own speeches and online marketing.

“The civil rights movement didn’t care about getting KKK members part of their movement,” says Hussein. “These issues are really quite big issues, and they cut through society – you’ve got to pick a side.”

The civil rights movement didn’t care about getting KKK members part of their movement…These issues are really quite big issues, and they cut through society – you’ve got to pick a side.

“Internal Strife”

Hussein’s fear is not that movements will fracture if they become “more political”, but that they will fracture if they don’t have a clear and overt message that unites members.

“I worry about internal strife,” he admits. “There is a line right down XR where you have people of a more socialist leaning, and people who have a much more reformist leaning.”

Hussein says that not having a clear political stance and having a confusion of different views makes the group weak and easily to infiltrate.

“It creates fertile ground for the police and the state to tear it apart from the inside,” he says.

It sounds far-fetched, but it’s happened before.

Back in 2003, police officer Mark Kennedy began a double-life as a political activist for seven years. During this time he infiltrated environmentalist, anarchist and anti-racist groups, whilst feeding information back to the Met police. With climate change the definitive issue of our time, Hussein is adamant it could happen again.

According to Hussein, XR “really underestimates the state.” He also points out that a lot of XR activists don’t even consider the possibility of police spies due to a lack of experience with the police and political activism.

It seems that a “lack of experience” underpins the movement in so many ways. Not only a lack of experience in activism, but a lack of experience with struggle – struggle with poverty, with racism, or with the consequences of climate change.

Whereas movements such as the Civil Rights movement were made up of people on the frontlines of racial discrimination and inequality, XR is made up of a “mishmash” of politics – with some members siding with Hussein’s intersectional socialism, and others taking a less radical, more reformist approach.

XR have no doubt got more people than ever talking about the climate crisis. However, it is clear that Hussein has doubts about the movement’s future, and how long he can keep trying to bring about change from within.

“I can only go so far,” he tells me. “To be honest, I’m not optimistic.”

For Dr Allen, who has studied environmental movements throughout her career so far – watching the rise and fall of many – she says it will be interesting to see how things turn out.

“Social movements have a history of starting out really strong, getting some big wins,” she says. “[But] how you keep momentum is really difficult.”

She notes that a reassessment of strategies may be necessary as XR move forward.

“[Civil disobedience] is one tool in the tool box – now they’ve used it, and the question is – what now? Whenever you take that extreme action…you risk marginalising a bunch of people.”

Hussein maintains that XR will become stronger if they march alongside other groups.

“One big thing I keep saying we have to do is we [have] got to build a coalition of forces. We’ve got to be working hand-in-hand with Wretched of the Earth, LGBT groups, anti-racism groups.”

Hussein will also be holding several intense sessions on climate justice, race, class and inclusivity with XR, in hope of educating members about how these issues interact, and why it is vital XR becomes more intersectional.

He says that the issues XR cover, and the groups they engage with – and don’t engage with – are essential in creating a welcoming environment where people of colour feel their voices really matter.

When I ask Hussein how you engage more black and minority ethnic activists, he says the answer is simple: “you talk about issues that are relevant to them.

You talk about pollution, you talk about toxic waste, you talk about all those things happening in their communities, the infrastructure, war, all the things that resonate with them.”

Dr Allen agrees.

“These are the types of stories that can really help galvanise people,” she says. “And these are the types of stories that Extinction Rebellion are not geared to tell.”

It is interesting to see how power dynamics operate even within social movements. If XR is led mainly by middle-class, white academics, does this really pave the way for radical change?

Dr Allen says it is crucial to have a set of voices around the table that reflect the reality of living on the frontlines of environmental inequality, austerity, and structural racism.

“If you have a bunch of white men around the table, they might not think about how some people can’t access bank accounts straight away, or maybe couldn’t afford to pay out a carbon tax, that might be, let’s say, fifty pounds a month,” she says.

She also notes the responsibility of white activists to know when to step aside:

“For me, an environmental campaigner means you also stand up for those on the margins, in a way that’s respectful and inclusive for them,” she says.

“And if that means they say, look we’re not involved in the organisation, that means you say, okay, let’s find a way to help you, or to get you involved, and to listen to you.”

For me, an environmental campaigner means you also stand up for those on the margins, in a way that’s respectful and inclusive for them.

Hussein believes that in order to bring about the radical systemic change that XR are so keen to see, there needs to be a shift in who is leading the fight.

“The world is on fire – so what society do you want to build?” asks Hussein. “Do you just want to create a replica – where the same people’s voices are always heard?”

XR has spread like wildfire across the globe, and the movement – if nothing else – has got people talking and caring about climate change, but they cannot bring about radical change if they are not listening to even their closest critics.

Hussein’s relentless determination to bring about not only environmental and political change, but also change within XR, is encouraging, but it is equally up to XR to listen to the voices who are demanding to be heard.

One thing is for certain though – radical, uncompromised and unprecedented change cannot come about without radical, uncompromising and unprecedented voices and ideas.

As our interview draws to an end, Hussein drains the last of his coffee and smiles:

“Jean-Paul Sartre, the writer, said that whenever he looked back at something in his life, the biggest regret he had wasn’t that he was too radical – it was that he wasn’t radical enough.”

“You know, XR need to take that,” he laughs. “You’re not going to make friends everywhere.”