Greek student political organizations have always been some of the most active schemes amongst young people, yet involvement in universities’ elections and political collectives doesn’t appeal to students anymore. Why political participation in universities is losing its dynamics during the last decade?

A few metres away from the restaurant on the second floor of the Department of Computer Engineering and Informatics (CEID) at university of Patras, a group of a girl and five boys are sitting on an array of wooden desks, wiggling their legs and raising their voices which are echoing the corridors. The restaurant area looks like a colorful battle of posters on the walls, hanging off desks and leaflets on the floor.

Despite the fact that we’re not in the pre- universities’ elections period, rallying cries and political societies’ slogans have been disjointedly placed on the grey walls of the old educational institution. The University of Patras is the third largest university in Greece and one of the most politically active institutions, with dynamic and radical student groups, which are active inside and outside the university.

“Right now I’m the only one who represents Arasyn at my department and I’m graduating next year. There is no-one after me to keep the organization alive in my university,” says Georgia Nikolakopoulou, student at CEID, in Patra’s University and member of Arasyn, a radical left-wing front, active in universities and the workplace society. After 2015 referendum, the left-wing politics faced the crisis of breakaway, between the collectives who supported the elected radical-left Syriza government despite their post-referendum era decisions, and the ones who split off, opposing to the radical left’s overturn. This phenomenon has been transferred to universities’ fronts as well, leading to a chaotic division of the radical left groups.

Vasilis Kalogirou, student at Patras’ University, is a member of AR.DI.N, a radical left front, which had affiliations with Syriza until 2012. As he explains, in the current socio-political environment, the left today is fragmented in many hegemonic tendencies without willing of cooperation and agreement in one common goal which could unite them. The splitting off of the left-wing groups and the creation of many small ones, with different beliefs each, makes it difficult for a student who is not familiar with the left to find the one which is closer to his beliefs. In this case, the micro-society of universities seems to be reflecting the environment for the radical left in general politics as well.

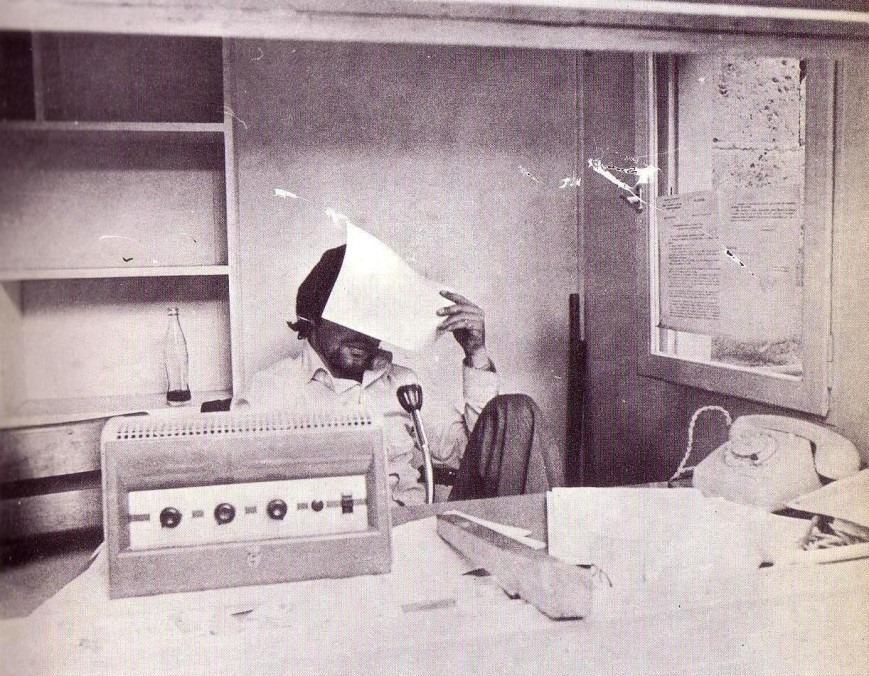

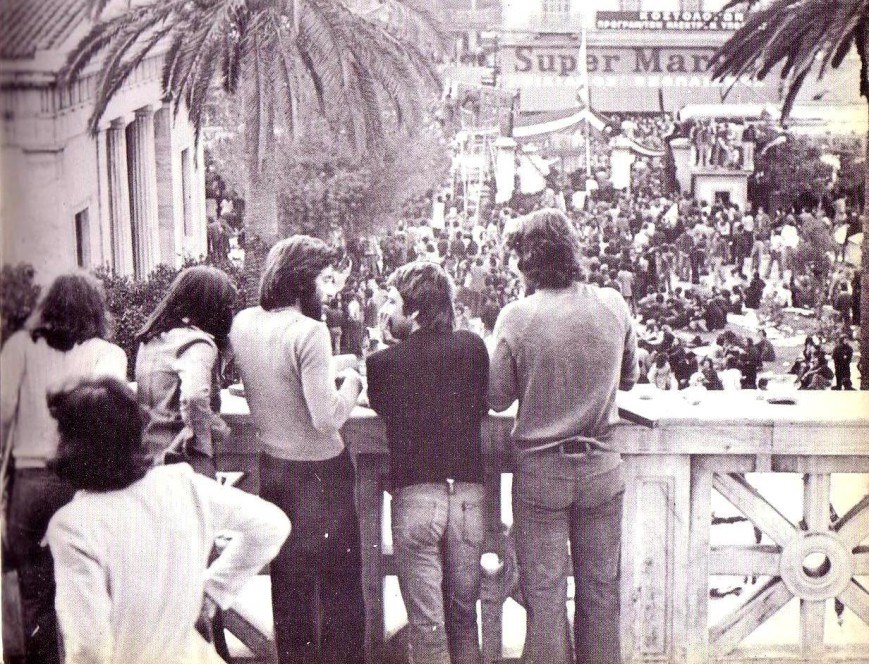

Students have been the voice of the The Athens Polytechnic Uprising. (Photo on @safeaak on Facebook)

The students’ protests of November 1973 were the starting point for the fall of the junta regime in Greece.

(Photo on @safeaak on Facebook)

It was 17th of November, at 3 am when the tank crashed the gate of the Polytechneio campus.

(Photo on @safeaak on Facebook)

Young people in universities have always been the radical voice of the country, standing against governments’ decisions and law’s implementations, yet, the radical left part of higher education today appears not to have the ways to engage students in active participation in fronts. As Vasilis explains, people are disappointed by the general political environment and that disengages them from politics in universities as well. Universities in many ways are a miniature of society.

When the active spirit of society is lessening, at universities it’s diminishing even more, a clear example of this is that Syriza’s youth front power has declined after 2015,” says Thymios Dragotis, PhD student at Patras’ University and active member of left organizations in Patras since being a student.

“University is a place that creates political consciousness, but that’s not enough to make someone get involved with collectives,” says Theodoros Chatzipantelis, Professor of Applied Statistics at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Political fronts in universities have always been a red flag for first-year students and the prejudice against political participation in universities has led the majority of the students to avoid the fronts or any activism and involvement in the university’s sphere. As Thymios explains, students don’t see the power of the collectives anymore, even in society, people don’t see that their opinion is taken into account and they can make difference through collectives. Thymios recalls the massive protests of 2006-2007, when students were protesting against the change of a law that would impact their studies. Back then, universities’ occupations, rallies and protests against the political system had the power to make change. “We do believe in making change, the students we communicate with do not believe so,” says Vasilis.

“On the one hand many students drop off political groups and on the other hand, there is no new blood to join the collectives,” says Georgia. Even in protests, as Vasilis explains, during the last five years, he always sees familiar faces, there are always the same 100 people they were at the last protest and that means that the participants are not renewed.

Georgia and Vasilis are both members of radical-left fronts and as they both agree, the disintegrated left has to change its speech and its communications strategy in order to attract people. The deep philosophical and idealistic speech of the left is difficult for people who are not involved in the left to understand and also, it doesn’t speak directly to the everyday needs the students want to cover. “Students act only on issues they really touch them, they are not interested in further involvement with fronts. There have been issues where students who didn’t belong to any front were the core of the protest,” says Georgia

Banners that are going to be placed on the istitution’s walls are prepared by the fronts.

(Photo on @safeaak on Facebook)

Banner of a students’ front in National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, School of Philosophy

(Photo on @safeaak on facebook)

Students’ fronts are almost entirely representing big political parties inside Greek universities. During the past years, the fronts of the two predominant political parties in Greece, the right-wing (DAP-NDFK) and the central-socialistic one (PASP) had serious power in universities. Despite the past glory the two fronts had in universities and their power in decision-making processes, this era seems to have ended. “We realised that the way we were acting was against us. We appeared to be a group of people only interested in throwing parties and organising holidays for students,” says Vasilis Kalogirou, member of DAP-NDFK at University of Athens. “There are some collectives that are less strong outside the university, like the communist party, yet, PKS, its front in universities has significant power in young people and students,” says Mr. Chatzipantelis.

“Students find no reason or merit to participate in any collective body or process, they just want to finish their studies in time,” says Mr. Chatzipantelis. For a student to be active in direct democracy processes while being a student at higher education, it’s not only to be a member of a student’s front. Participation at the general assemblies of the students’ community, as long as voting at the students’ elections are major factors that signify political participation in the small world of universities. However, councils are repeatedly being held without the minimum number of participants and participation in elections, in some departments are a single-digit percentage. Even in departments with higher participation in elections, the number doesn’t exceed 20 %.

“University is a place that creates political consciousness, but that’s not enough to make someone get involved with collectives”.

Theodoros chatzipantelis, professor at aristotle university of Thessaloniki

“Assemblies are not organised for the fronts, they are organised for the students,” says Georgia, still, with no participation of the students’ voice, they become an arena for political and ideological dispute amongst factions. As Mr. Chatzipantelis explains, most of the issues discussed in general assemblies deal with general and big issues of the society that students are not directly appealing to tackle at that moment of their life.

Students’ fronts in universities have become politically aware of issues, such as work conditions, human rights, and unemployment in order to address issues students will face out in the society after their four-year studies. As Thymios explains, engaging students while being in a students’ front with the general ideology of the front itself is a way of keeping them inside the circles of the political ideology afterwards. In this way, as he says, the fronts increase the numbers of its supporters at the greater political scene.

It’s an open secret that, especially in the past, many students were involving with students’ fronts in order to facilitate their prospect life, by entering the party’s community and assure themselves a job or facilitation in a work environment. Clientage in universities is not something about both the academic society and the outside world had no idea. Even if this patronage is not as strong as in the past years, the fronts are always looking for their members’ long-term accession. “The level of occupation at university defines the future engagement of that person,” says Thymios.

Universities’ students have been the cradle of activism and action in many cases before in Greek society. The existence of political fronts in the corridors of the higher education institutions was a voice speaking for direct democracy amongst young people. The discussions supporting the abolition of the political students’ fronts in universities find the aforementioned in the middle of a crisis. Both the left and the right are trying to redefine themselves and to form an instrument that engages students with active participation in decision-making processes. What’s left to see is whether students’ organizations can be the ones to throw off the trammels of the past and to regenerate students’ interest in active participation within the small world called university.

Featured image: Dimitris Lampropoulos