In 2016 the Isle of Man was named a UNESCO Biosphere, celebrating the link between the language and the land, meaning what for the future of the language and culture of the small island?

The ram stares at me, chewing placidly and seemingly unbothered by the pieces of grass falling out the side of his mouth. Behind him, I see a ewe and her lambs, looking at me with slightly more alarm, waiting on the ram’s decision. My way back lies past the sheep, but the hedgerows on either side of the path are too tall and thick to go around the sheep. No help for it, I guess I just have to go for it. I step forward, the ram stops chewing. Another step, and the sheep startle, leaping over the verge. Mr Ram and I continue our staring contest until he is out of sight, blending into the rolling hills near the small village of Kirk Patrick.

Today, I had hiked the fifth stage of the Raad ny Foillan path from Niarbyl to Peel on the western side of the Isle of Man. The trail follows the coast of the Isle of Man from the capital city of Douglas through Port Erin, Peel and Ramsey before arriving back in Douglas. Raad ny Foillan translates to “Way of the Gull” in Manx Gaelic, the native language of the Isle of Man.

Some people choose to walk the trail in whole, while others may choose to do only a couple stages out of order. You can walk for hours and not see anything other than gulls soaring above, giving plenty of time to take in the views across the Irish Sea or, if it’s a rainy day, the distance to the next pub or café. The Raad ny Foillan is known for its wildlife spotting – seals, basking sharks, the elusive Manx cat, wallabies – as well as giving walkers a chance to see all the different parts of the island, from breath-taking cliffs to sandy beaches, rolling hills dotted with sheep and cows to mountains reaching for the clouds.

The Raad ny Foillan is one of the primary elements that helped the Isle of Man to receive the designation of a UNESCO Biosphere space in 2016. A UNESCO Biosphere is an area that contains coastal, land and marine ecosystems and promotes biodiversity conservation and sustainable use. The Isle of Man is unique in that it is the first island nation where the whole island has received the designation, instead of just a small reserve.

“It’s a great opportunity again for us to…to get us certainty and security for the evolution of the country,” says Phil Gawne, who, along with Dr Peter Bridgewater, drafted the application for the biosphere designation. The island has plenty of UNESCO heritage sites, but the biosphere classification helps to marry the past with the present, developing an understanding of the history of the Isle of Man and making it relevant to recent developments with Manx culture and language.

Just approaching the island by ferry, there is already a sense of how connected the island is to its environment. The port city of Douglas quickly gives way to rolling fields in any direction, and to the north, you can see Mt Snaefell, if it isn’t shrouded in clouds. During my wanders around the island, I could see how much the landscape has shaped the lives of the people who live here. Approximately 571 km2, the island boasts a rich diversity from rolling farmlands to wooded glens, rocky beaches to imposing sea cliffs.

Located in the middle of the Irish Sea, the first settlers of the island would have quickly learned to be self-sufficient, and a knowledge of the land would have been a must. The words they used to describe the soil, the shape of the land, everything, would have significant meaning for what could be planted where, or if the space was better for sheep or cows.

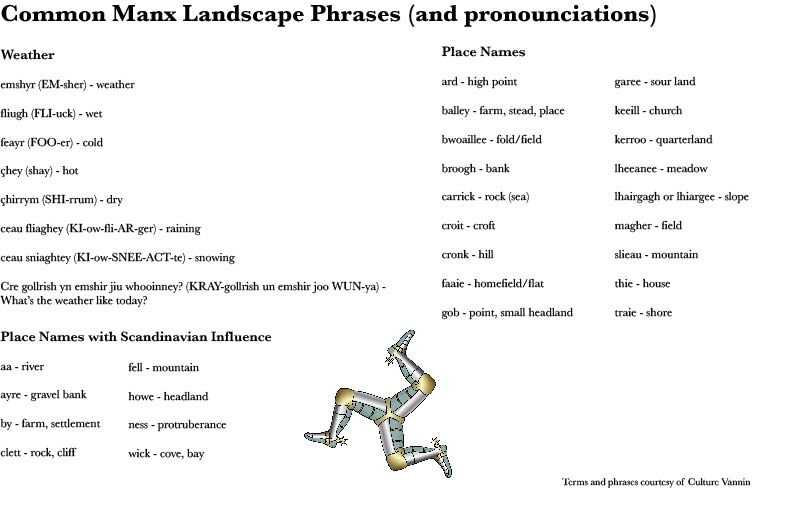

“Some places, the names refer to the type of soil,” says Aalin Clague, a Manx speaker who was born and raised on the Island. “So, if you know what the name means, then you can understand the soil, what can be planted there, or what kinds of animals can graze there.”

The island has long celebrated its relationship to the land. The Laxey Wheel is one of the largest river wheels in the UK and powered the mine at Laxey for over seventy years before becoming one of the Island’s most popular tourist attractions, and as you take the bus south to Castletown or Port Erin, tradition dictates you say “hello” to the moojiner veggey (wee folk) as you pass over the faerie bridge.

While Manx is no longer commonly spoken across the island, having faded almost into obscurity in the 60s and 70s, many places retained their Manx names. Individuals like Clague and her mother, both Manx speakers, talk about how learning Manx gives people the opportunity to understand where the names come from, and do their best to share it with others, like Lucy Partington. Partington is learning Manx through an apprenticeship program because she wants to feel more of a part of the island and its culture.

“I grew up here but didn’t learn Manx in school. Now that I’m older, I want to know what place names mean,” says Partington, who meets with Clague’s mother, an experienced Manx speaker, once a week to practice Manx. In order to better grasp the language, the pair speak about everything from books they are reading to activities they did over the last week.

“You don’t want the culture to feel as though it just belongs to one part of the community, one part of the island,” says Dr Breesha Maddrell, the director of Culture Vannin, a part of a charity called the Manx Heritage Foundation. Like everyone else I talked to, she wanted to highlight the importance of the Manx-ness of the Island that stretched beyond just the language.

“Culture is the unseen fourth leg of the biosphere, and language,” said Dr Peter Bridgewater, a former global director of the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme and a current member of the Intergovernmental Coordinating Council, at his lecture, “Don’t ask what your biosphere can do for you, but rather what you can do for your biosphere.”

Throughout his lecture, highlighting the distinctions between a UNESCO Heritage Site and a Biosphere, how it benefits the Island and vice versa, Bridgewater kept coming back to the idea of culture and language being just as integral a part of the Island as the natural resources, sites and the like. Questions at the end of the lecture also surrounded the idea of the language and culture, in addition to the importance of the land itself.

As I left the lecture, I ran into Maddrell, who exclaimed excitedly, “See! What we’re doing is really important!”

As I wrapped up my hike, I couldn’t help but agree with Maddrell, Clague, Gawne and all the other people I had met. Yes, the Isle of Man is breathtakingly beautiful and full of life, and anyone can visit and enjoy the sites and sounds of the small island, but when unearthing the layers of culture, well, the Isle of Man all but speaks for itself.