Grassroots organizations were the key driving forces of civil society operation during the period of the Greek crisis, yet, their strength has significantly declined since 2015. Why was social activism weakened and what does this suggest on political engagement?

The three middle-aged men at the table close to the sea are raising their hands to order ouzo. The sound of their glasses clinking is mixed with the different tones of their voices raising one above the other. It is the middle of summer and despite the hot weather in Greece, political conversations are still the reason why voices raise around a table and plenty of ouzo.

For Greece, the home of democracy, politics have always been on the table for discussion but mainly, for active participation in a try to make change and to promote democracy themselves. The outburst of the financial crisis in 2009, gave birth to many grassroots collectives as a form of collaboration to solve the everyday issues that the new era has raised.

For Mehran Khalili, a British-Iranian photojournalist who moved to Greece at that period, the activist spirit the Greeks had and their political awareness in practice was something that drew his attention. The plethora of the grassroots groups that were acting around the country was the proof that Greeks were not the ‘lazy, ouzo-drinking’ Europeans that were pictured in the media, but in fact, people were trying to make change in every possible field of common interest. In June 2014, when Omikron project’s grassroots map was published, it included more than 400 active non-profit organizations, from human rights collectives to democracy and neighborhood political assemblies. Four years after Syriza’s radical left party government, the links which lead to the official pages of almost all of these groups lead to one common result, “error. Page not found”.

“Just after Syriza got elected, in January 2015, the activist spirit turned into a ‘wait and see’ mode,” says Mehran. After a long period of uncertainty and instability, the left-wing Syriza government re-defined not only the political image of Greece to Europe, but also, with its pre-elections promises, it seemed that they came to take the role and solve many of the problems that the so-called grassroots groups were trying to manage all these years.

Since January, when Syriza got elected for the first time, and the referendum at the beginning of July, there was a period of continuous negotiations that raised people’s confrontation about Greece’s exit from the crisis. Under the sentiment of hope that change is coming, political activism was covered under a passive reaction towards the new era. The “what are we going to do here on the ground?” question which created the movements of the squares and the grassroots activism was replaced by political discussions and a ‘waiting for what’s going to happen’ mode, explains Mehran.

The new government itself “had absorbed many of these groups, taking away the oxygen, the rationale part of them”, says Mehran, The radical and organizational part of these groups lost its dynamic and sharply faded out since many of these organizations had affiliations with Syriza, with some of their key people straightly joining into the party when it became government, he explains.

“The collectives stopped because they got destroyed by political mechanisms. Even the people behind the squares’ movement, they just wanted to politically manipulate people,” says Giannis Krousos. Giannis is one of the founder members of the grassroots group IthacaNet, one of the few groups whose website appears to be still active. However, an active website doesn’t mean that the collective is active in practice too. Organized political movements penetrated many dynamic grassroots groups in a try to impose their organizational skills, and re-define activism purposes. Whenever political colouring interfered with grassroots organizations, participants were coming away.

The movements of the squares, in 2010-2012, were the place where a late adolescent revolution stemmed from the Greek society, as Penelope Foundethaki, Professor of Political Sociology and Comparative Politics at Panteion University claims. “It was a movement that reminded of May 1968, with people flooding streets and squares protesting,” she adds.

However, the same squares became the foundation for grassroots activism to stem in modern Greece. Mehran remembers having friends who, along with hundreds of other people joined the protests at Syntagma square, without clearly knowing its purpose beforehand. In fact, it was going to the square when they came along with collectives and groups, active in different kinds of activism. People who had no deep knowledge about politics but they just wanted to change the political and social landscape they were living in, gathered under the umbrella of power of the people to redeem.

“The new government itself “had absorbed many of these groups, taking away the oxygen, the rationale part of them” .

Μehran Khalili

The power of the movements was giving hope for change and people had expectations that these groups could actually do something. Despite the dynamics of that era, little impact had in reality as far as the political decisions are concerned. “After a long time of no result, everyone went back to their business, the fire extinguished,” says Mr. Giannis.

Thymios Dragotis is a PhD student at the University of Patras and he’s actively participating in political organizations in the city where he lives. Despite the strong activist spirit the city of Patras had during the crisis period, today, as Thymios says, citizens don’t easily take action anymore and sometimes, organizations like the one he belongs in, are trying to motivate them and organize them. “There were much more of these attempts, but there are almost none of them anymore. After 2015 the sense of defeatism eradicated them,” says Thymios.

“The reverse of the referendum’s result probably had an impact on people’s aloofness. I have friends of mine who felt incredibly dejected and that they can have no influence on decision-making processes,” Mehran explains, adding that the grassroots collectives of that period, they should understand the great impact they could have and be showcased as an inspiration for other people to do the same. “Unfortunately, that didn’t happen,” as he says.

Anti-austerity protests and squares’ movements have been reinforced by the participation of the radical left groups, including Syriza which in 2015 became the government, elected from the people in order to bring people’s voice in the parliament and on the table of negotiations with Troika. The failure of Syriza and the pre-elections promises’ overturn had not only effects on the socio-political environment in Greece. Most importantly, as Thymios explains, people believe that they can’t get anything from protesting because the same group of people who demonstrated with them before, they are against them now.

Despite the fact that Greeks nowadays seem politically disengaged, as Mehran Khalili says, they are deeply aware of politics, and that gives aspiration for grassroots activism to arise again, in a new context. The main problem that needs to be solved, as Mehran explains is the lack of a clear target. The activism of 2010-2012 had an enemy to fight, a goal to achieve, yet today, there is no clear target anymore. “With the ground getting lost, there is no set for action,” adds Minas Konstantinou, journalist at The Press Project.

Involvement with grassroots activism requires time and energy. Everyday life changed during the fiscal austerity period, driving more and more people in focusing on covering first-hand needs and even poverty. Today, IthacaNet is composed by Mr. Giannis and two other people. As he says, “in numbers, we are more but in active participation, it’s just the three of us anymore. We’re friends, even with different political ideologies, we still fight for a common goal”.

The refugee crisis which Greece is highly experiencing is an indicative example of re-enforcement of the activism spirit after the period of 2015, even though many of the organizations that were trying to tackle the issue quickly transformed into NGOs. People’s perception towards immigration, refugees and racism has changed for the better and this form of activism was a significant factor why that happened, yet, the political parties’ flagship inside these groups is nothing but a suppressing factor.

“We need to find how to capitalise the energy people have. If it doesn’t find an outlet it will fizzle away in small-scale activities, which is beautiful as well, but it might not have the impact a big part of a grassroots group could have,” says Mehran. Greece may be the birthplace of direct democracy, yet it’s never been the foundation of grassroots political activism. The financial crisis-era sparked a sense of act from below in order to make change at the top but the fire didn’t really arouse. In a surrendered society which still lives in austerity, as Mehran says, the natural spark which generated the movements of the past, with a freestanding organization, yet, it needs to re-attach to the Greek society with a clear purpose.

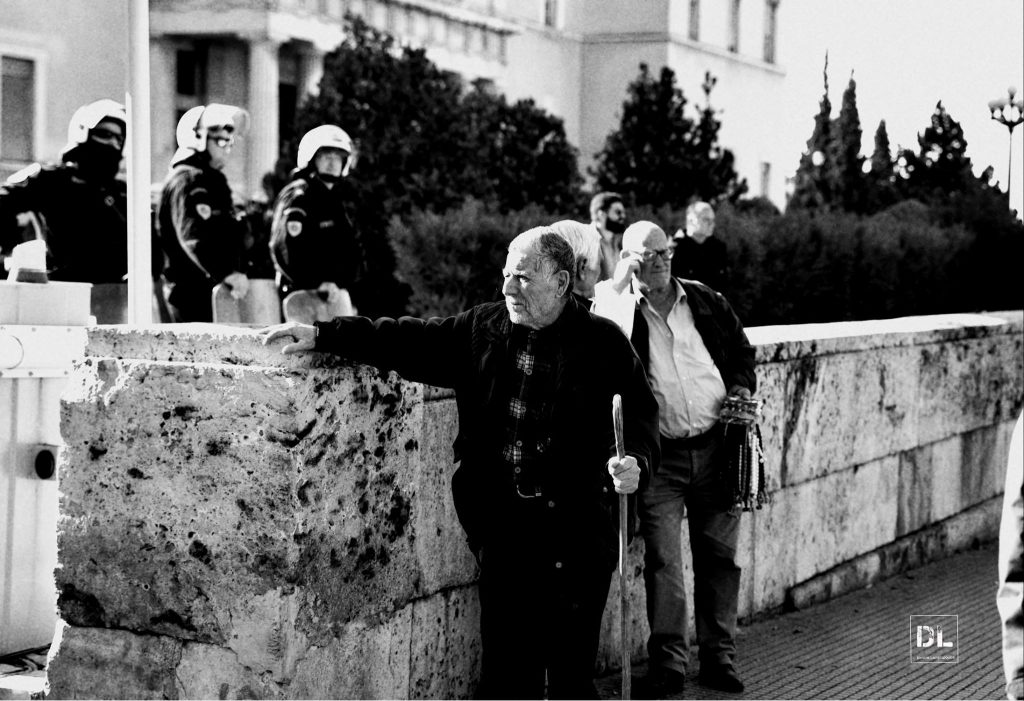

Featured image: Dimitris Lampropoulos